Sure, a monster bursting into your bedroom in the middle of night is scary, but a simple mysterious creak from a shadowy corner? A sense that someone is there, watching you, unseen? Ghouls and vampires are bad news, but an invisible man? Well, that’s terrifying.

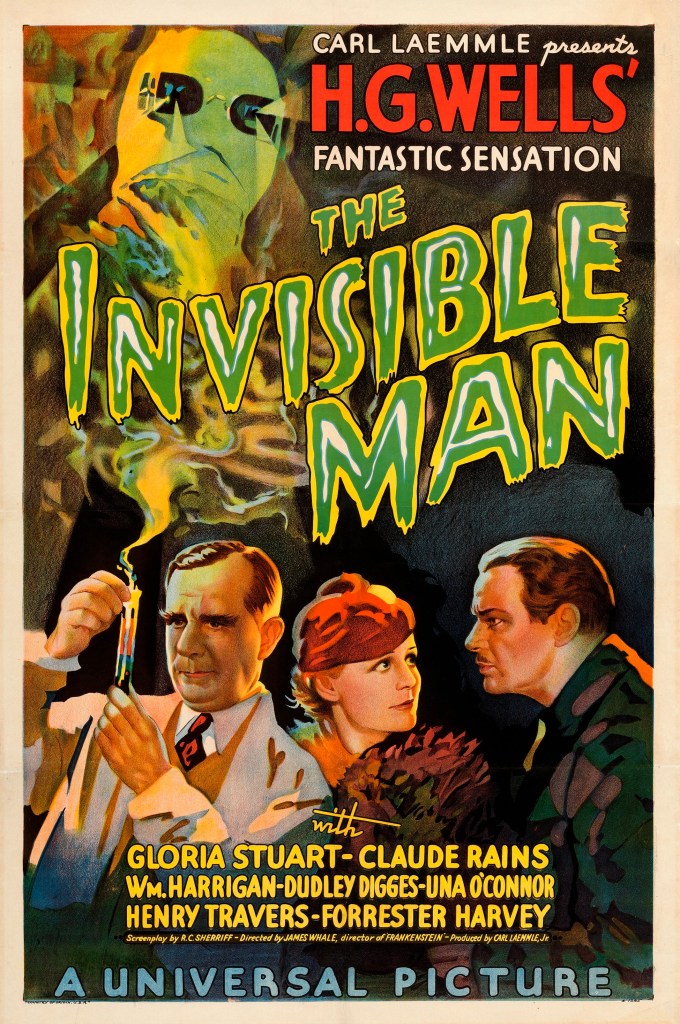

James Whale’s 1933 film The Invisible Man turns 90 years old later this year, and remains a quick-witted, vivid early science-fiction thriller.

I sat down with the 19-year-old to watch it again recently, and at the end, he turned to me and said with a note of surprise, “That was really good!” Not all of those sometimes antiquated black-and-white horrors would get that kind of reaction, but The Invisible Man remains a model of slick, efficient filmmaking, in and out in just over an hour’s run time.

The story is simple – a man turns himself invisible, and is trying to find a cure. But the experimental formula he tampered with is also slowly driving him insane.

The Invisible Man is one I watch every few years and clustered right up there in the top 3 Universal Horror movies for me (jostling with, of course, my beloved Creature from the Black Lagoon and depending on my mood that day, either James Whale’s Frankenstein or Bride of Frankenstein).

Whale was the best of the classic horror directors, lending a keen visual eye and a wry sense of camp to his scare-fests. Pairing him with the stage actor Claude Rains here was a masterstroke, because for huge sections of the picture the Invisible Man has to carry the film with his voice alone, and Rains’ purring, manic mad scientist is a gleeful delight, pinballing between vicious cruelty and tragic victim. (Originally Frankenstein’s Boris Karloff was tipped for the role, and while I love Karloff, it’s hard to imagine his sinister invisible growl having quite the same impact.)

Based on H.G. Wells’ thrilling novella, Jack Griffith, the Invisible Man, is instantly a striking figure from his first moment on screen, wrapped in bandages and dark glasses, a simple but brilliantly effective way of rendering the character visible when he needs to be. The special effects are remarkably good for 1933, a few wires and puppetry seamlessly creating the illusion of a man who isn’t there.

The Invisible Man also unique in the classic Universal Horror menagerie because Griffith is very much an ordinary man who did this to himself, not some mythical creature like Dracula or the Mummy or a victim of others’ meddling or evil like Frankenstein’s monster or the Wolf Man. He is human, which makes his crimes that much more brutal.

Griffith: “An invisible man can rule the world. Nobody will see him come, nobody will see him go. He can hear every secret. He can rob, rape and kill!”

And hang on to your hats – with more than 100 people murdered during his reign of terror, the Invisible Man actually had the highest body count on screen of any Universal monster – more than Frankenstein’s creation, more than Dracula. Sure, most of that is the terrifying train derailment he causes near the movie’s climax, but Griffith still strangles, assaults and terrorises with gleeful abandon.

Coming as The Invisible Man did in that delicate global tension between the devastation of World War I and the genocide of World War II, it’s hard not to see many a would-be dictator’s fantasies in Griffith’s speeches.

Invisibility is a curious dual curse and blessing in the world of horror – you could go anywhere, in theory, do anything, but if you can’t turn it on and off, you’re also forever separate from the human race, a witness without an audience.

The concept has been revisited many times, in a series of gradually less effective sequels in the ‘40s, none of which starred Rains, and a goofy Invisible Woman movie in 1940 that made the concept into a laboured comedy with a lot of teasing innuendo, but generally invisibility seen on screen is a man’s world.

More modern movies like Kevin Bacon’s 2000 slasher flick The Hollow Man and the excellent 2020 Invisible Man starring Elisabeth Moss leaned into the Invisible Man’s toxic masculinity with mixed results but there’s something to that – an Invisible Man also implies sex (generally in these films, you’ve got to be naked to be truly invisible, after all) and stalking and predation, factors most of the Invisible Man movies dip into. To be honest, to be invisible is generally to be up to no good, isn’t it?

And looming over all those spectres is the inimitable Claude Rains, who 90 years on has yet to be truly bettered in the niche world of invisible horror movie villains. From that unforgettable bandage-clad visage to the cackling madness echoing through his voice, Rains still shows us that there’s nothing quite as scary as what you can’t see at all.

3 thoughts on “‘The Invisible Man’ at 90 – still a sight to behold”