Back in the misty 1990s, what seemed rare and fanciful suddenly started happening all the time – crossovers between the comics characters of the Marvel and DC Universe.

There had been crossovers for a while, starting with 1976’s gold standard of a super-meet-up, Superman Vs. The Amazing Spider-Man. There’s still few things better than the goofy charms of this comic, watching the Man of Steel and webhead meet, fight and team up, originally told in a massive tabloid-size edition.

It was a hit, so others followed – Batman and the Hulk, the Teen Titans and the X-Men, and they were pretty good, too. Then there was a long lull, until in the 1990s we started getting crossovers all the time – Batman/Spawn, Batman/Punisher, Batman/Daredevil, and probably some that didn’t have Batman. They were less inspired than the first few, lacking the thrill of the new, and mired in that same generic gritted-teeth stoicism that marred many 1990s superhero comics. Some were good – John Byrne’s Batman/Captain America totally rules – but nobody was dying for Spider-Man/Gen 13.

And then in 1996, the fanboy’s dream happened – an entire miniseries devoted to comic culture clashes, DC Vs. Marvel Comics! This would be great! Wouldn’t it?

But no, DC Vs. Marvel (or, Marvel Vs. DC) was … adequate. It’s not a complete failure, but it’s unsatisfying and never lives up to the potential dreamed up by a legion of teenage fanboys. It was a case of trying to do too much, in too little space. Instead of the room to breathe that the original Superman/Spider-Man meeting had, you had every character from two universes jammed together fighting for a couple of panels, tied together with some balderdash about cosmic “brothers” who were avatars of each universe… and then there was Access.

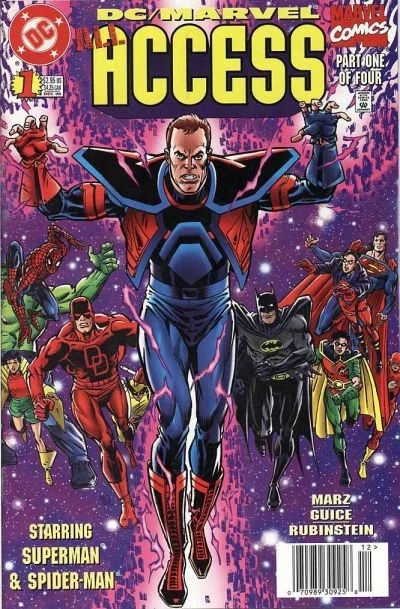

Meet Access, the superhero whose power is equivalent to that of your standard-issue functioning doorknob. A blandly generic kid named Axel Asher (owch), he gets named the “keeper” between the two universes. Access is meant to provide the balance between worlds, you see. If he doesn’t crazy, cosmic things will happen.

Of course, Access screws up, and the two universes merge, providing the somewhat cool spectacle of a line of “Amalgam” comics featuring mashup characters like Spider-Boy, Super Soldier and Dr. Strangefate who were the 1990s equivalent of the endless ‘multiverse’ stories we see today. They were fanboy service as comic characters, featured in a series of one-shots ranging from good to terrible before the whole underwhelming DC/Marvel crossover wrapped up.

There were lots of brief fun moments in the DC/Marvel mess – who wouldn’t want to see Superman fight the Hulk? And Dr. Strangefate is pretty cool. But generally, everything is rushed, rushed, rushed, and as a result it’s just a blur of capes and colours. Having a Silver Surfer/Green Lantern matchup dispatched in two pages or an Aquaman/Namor fight treated as a joke is just lazy. And honestly, you could ditch the entire Access/cosmic gateway stuff and just say “the universes crossed over because of a space-time anomaly” to streamline everything.

Access has to be just about the most boring character ever given the spotlight, a generic collection of ordinary-guy tics (he worries about his girlfriend!). So of course the publishers gave us not one but TWO forgettable miniseries focused on Mr. Doorknob and a never-ending parade of DC and Marvel guest stars, All Access and Unlimited Access. (Unfortunately, Access was never seen again after about 1997, sparing us Backstage Access.)

It’s hard not to yawn every time Access steps into a panel. He’s the superhero as plot device – at one point he’s explicitly described as having the power to “create crossovers” by staying in one place too long. His comics simply exist to throw Marvel and DC characters together in a variety of underwritten, overcrowded adventures. Reading the adventures of Access over several miniseries is like a hit of Pop-Rocks in Pepsi – it may give you a momentary buzz, but you’ll pay for it later. There hasn’t been another official DC/Marvel crossover in decades, and probably won’t be anytime soon.

I guess Access might’ve been ahead of his time as we seem rather overwhelmed by combinations and alternate versions of superheroes across the multiverses at the moment. Every fanboy likes to play “what if,” but when there’s no follow-up questions, you have to wonder what the point is.

That, or maybe Access was a harbinger of how starting in the 1990s superhero comics, in the end, started to eat themselves. No doorway needed.