Almost 40 years ago now, the DC Comics universe went through a bit of a crisis. Crisis On Infinite Earths debuted in April 1985 and was one of the first giant “shared universe” crossovers, a sprawling epic that brought together multiple worlds and changed them forever.

Meanwhile, just about at the same time, another universe-spanning 12-issue all-star miniseries was going on – but decades later it’s nearly forgotten, even though it was kind of the last gasp of that “pre-Crisis” universe.

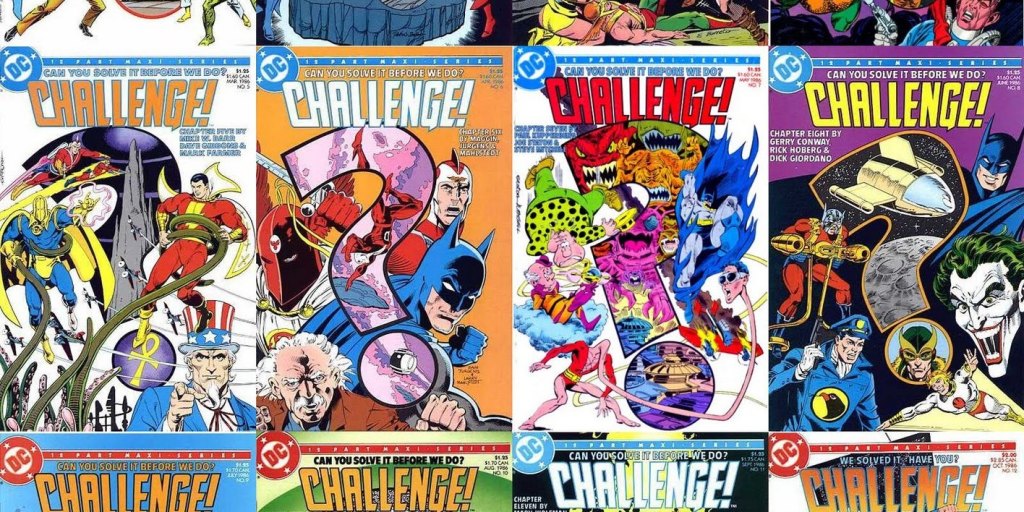

DC Challenge is a 12-part miniseries that also debuted in 1985, but instead of some carefully orchestrated event, it was a loose and wacky round robin jam comic where each issue was written and drawn by a different set of creators, bringing together everyone from the big guns like Superman and Batman to the obscure like Viking Prince, Congorilla and Adam Strange. Great comics writers and artists who played a big part in the ‘pre-Crisis’ DC Comics world joined in – Mark Evanier, Gerry Conway, Len Wein, Roy Thomas, Curt Swan, Gil Kane and many more.

Jam comics by their very nature are probably a little more fun for the creators than the reader, to be honest. They’re a creative exercise that stumbles along from player to player and resist any attempt to smooth out the bumpy transitions. But they’re also kind of fun because literally anything can happen.

DC Challenge is still an awful lot of goofy fun, maybe because it isn’t trying to change the entire comics universe. Instead, it’s a giant sandbox paying tribute to DC’s then-50-year-old history. Set outside “continuity,” it reads now as a kind of fond farewell to the pre-Crisis DC Universe where you’d regularly have Superman turned into a blimp by red kryptonite. A little less “serious” universe.

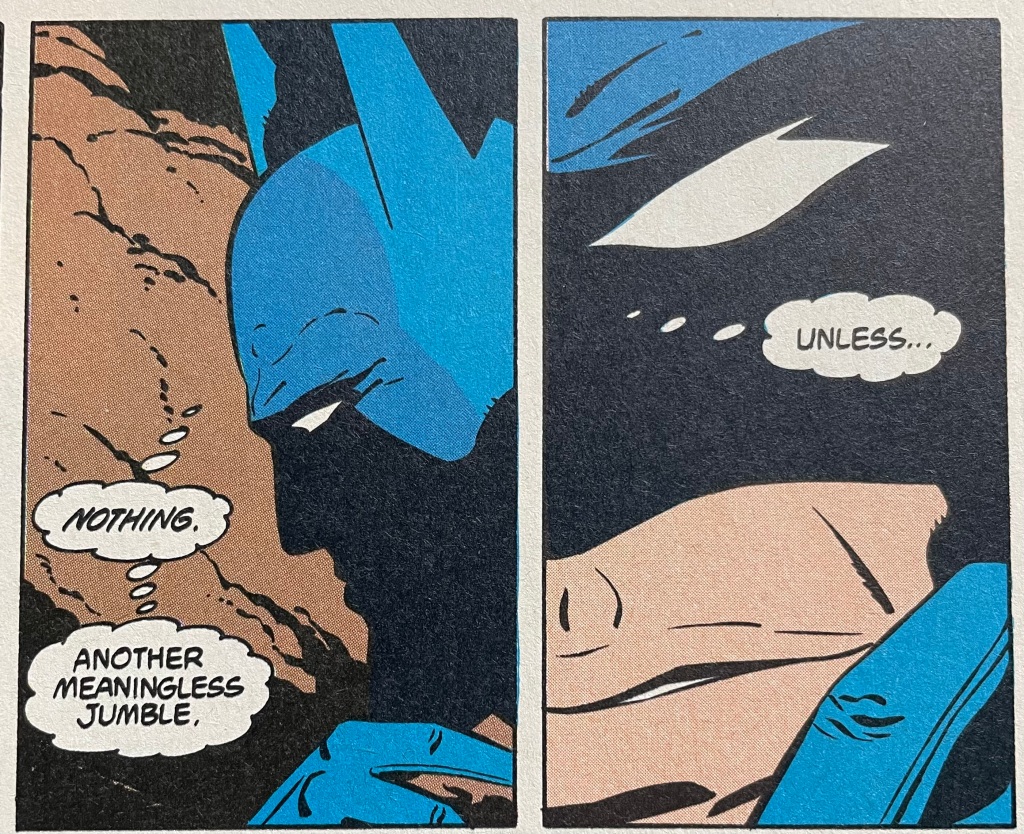

You get such oddities as cowboy Jonah Hex transported to the present day, Deadman teaming up with Plastic Man’s sidekick Woozy Winks, a Batman / Mr. Mxyzptlk encounter, a cameo by Humphrey Bogart, and creators pulling obscurity after obscurity from DC’s vast library of old characters, whether it’s Space Cabby or B’Wana Beast.

Is DC Challenge “good,” exactly? Not quite – it’s nowhere near as emotional or skilled a spectacle as Crisis On Infinite Earths with the late great George Perez’s stunning art, still my gold standard for everything-and-the-kitchen-sink comics storytelling. But it’s an awful lot of loose-limbed fun even when the story threatens to crumble entirely under the weight of a dozen or so authors trying to make sense of each other.

Sometimes a writer comes along and throws out a bunch of cool bits another threw in (at one point, Albert Einstein becomes an endearing cosmic-powered character in the DC Challenge carnival, only for rollickin’ Roy Thomas to come along in the last few issues and say it was just an alien pretending to be Einstein!). One of the more enjoyable part of the comics is the lengthy afterword essays each issue where the writers critique each others’ plot twists. More so than many comics, here you see the creative process laid bare.

Thirty-nine years on, DC Challenge is really only remembered by oddball comics fans like myself – it’s never been collected, is rarely referenced, whereas Crisis has been collected multiple times, adapted to TV shows and animated films, there’ve been at least a half-dozen “Crisis”-named sequels and it is still in many ways the template for giant comics crossovers to this day where we get swirling invasions from beyond and everybody and their brother teaming up to fight it all. (There was a nifty “Kamandi Challenge” DC put out a few years ago that did homage the round-robin concept, though.)

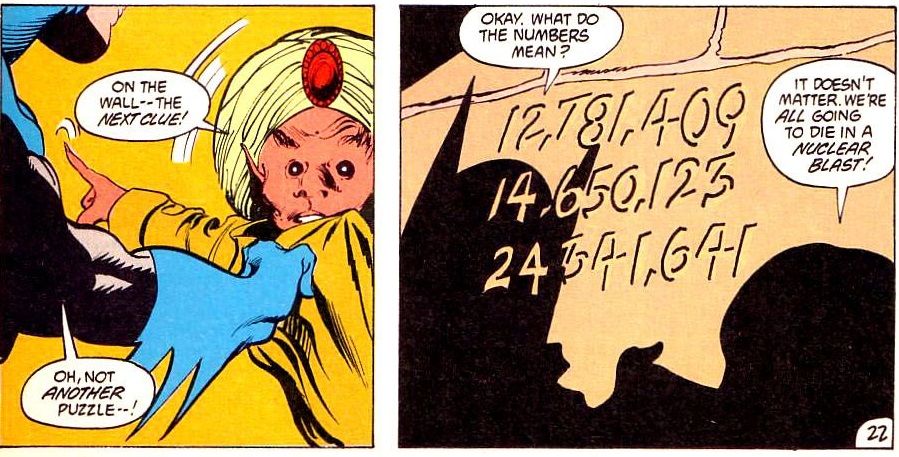

DC Challenge wasn’t helped by a kind of goofy catchphrase used to advertise it – “Can You Solve It Before We Do?” The thing is, DC Challenge wasn’t actually some kind of Sherlockian mystery, and the “challenge” really is each creator picking up the pieces after the cliffhangers the previous issue’s writer inserted. “Can You Follow The Insane Plot Twists?” wouldn’t be quite as good a catchphrase, however.

There’s been about a thousand big comics-universe spanning crossover events ever since Crisis and Marvel’s 1984 Secret Wars kicked the whole modern version of the concept off. Some are still pretty good, most are forgettable, but overall, the concept has been exploited for so much and so long that there’s no real novelty anymore in dozens of heroes gathering together under darkening skies to fight an unbeatable foe.

On the other hand, the madcap idea of just telling a fun story with your mates and seeing what weird roads it takes you on – well, it may not always be pretty, but it’s rarely ever boring.