I was a comic strip-reading kid addicted to the funny pages when I stumbled across a peculiar yellow book – more of a pamphlet, really – at a friend’s house, called Buy This Book Of Odd Bodkins by a guy called Dan O’Neill.

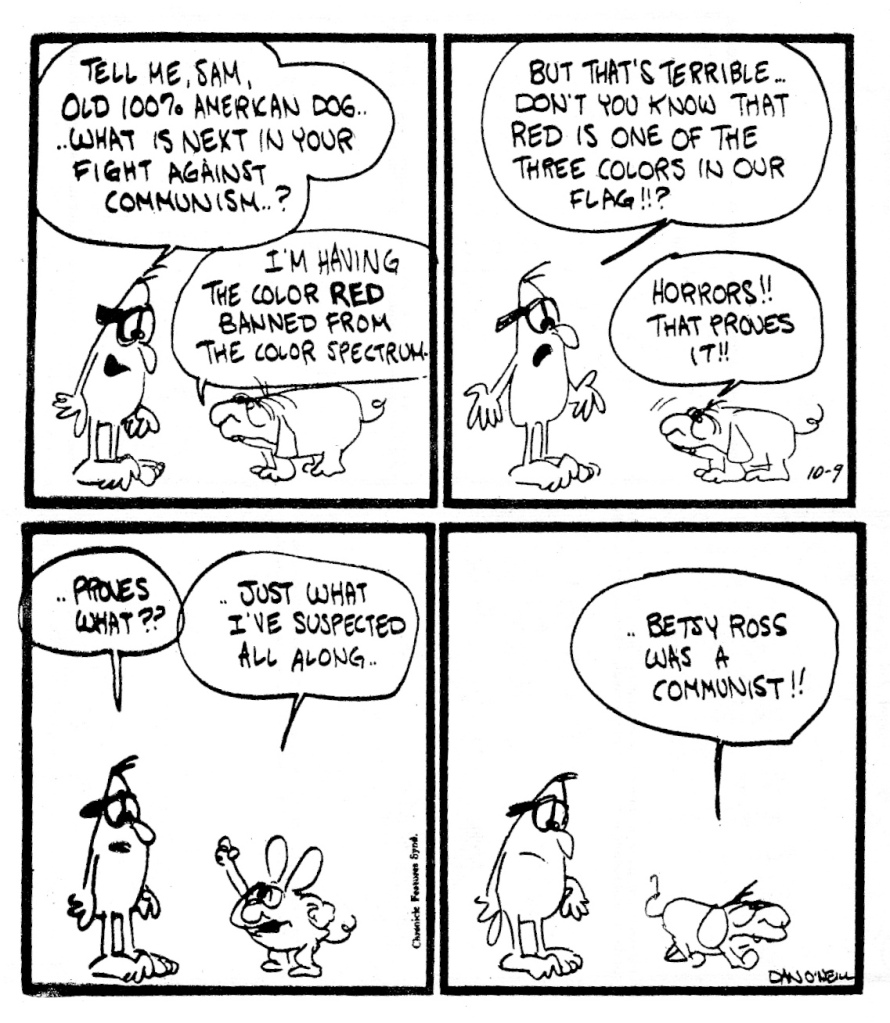

A curious little strip that ran in the San Francisco Chronicle from 1964 until he was fired (apparently for the final time) in 1970, Odd Bodkins began as the quixotic adventures of anthropomorphic birds Hugh and Fred, having wry discussions about current affairs and encounters with oddballs like the Batwinged Hamburger Snatcher, Smokey the Bear and the ghost of Abraham Lincoln. The early comics in that yellow book were slightly edgy, although in a kind of Doonesbury-esque subtle way, casting an askew eye at a topsy-turvy world.

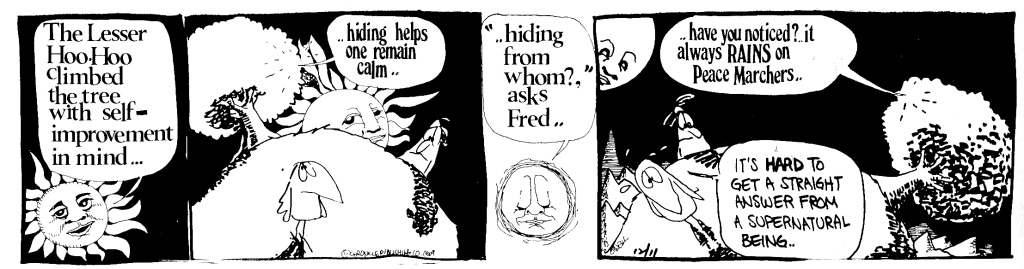

A few years later I found another book of Odd Bodkins, a big ol’ tome called The Collective Unconscience of Odd Bodkins, and man, that’s where things got weird. The same characters of Fred and Hugh were there but instead of gag strips they ambled along on an odyssey into the 1970s, and the comics got stranger and stranger, journeying to Mars and beyond. The backgrounds, nearly nonexistent in earlier strips, became swirling psychedelic landscapes, the lettering became baroque and extravagant, and the story, such as it was, became an extended walkabout in search for enlightenment in what felt like a world suspended at the end of time. The comics became far less about a punchline and more about a quest for meaning.

I didn’t quite get it all – a lot of the references were already ancient history by the time I read the comics – but I got it, you know? That was it. I was trippin’ on strips.

Once upon a time, iconoclasts didn’t mean crazed internet-addled sovereign citizen conspiracy theorists. O’Neill was one of the great independent thinkers and has never been afraid to stir the pot, or to, in the best editorial cartoonists’ tradition, cause good trouble.

Because he was publishing work in ‘mainstream’ media like the Chronicle, O’Neill couldn’t get quite as risque there as folks like R. Crumb, S. Clay Wilson and Gilbert Shelton did in underground comics. Yet that actually proved a strength, because forcing himself to draw ‘toons for the “straights” made O’Neill work harder to create bold, thoughtful strips without piling on the sex and drugs. He was the perfect gentle guide to more alternative viewpoints for me.

Of course, he could go “adult,” too. O’Neill is more widely famous for Air Pirates Funnies, a very adult X-rated parody of Disney’s Mickey Mouse that ended up in a copyright lawsuit that went all the way to the Supreme Court during the 1970s. Those are hilarious too in their own naughty way, if you’ve ever wondered what Mickey Mouse’s bits looked like. And the battle against Disney over these strips and the boundaries of what parody was and is is one of the great stories of creative freedom, wonderfully chronicled by Bob Levin in his exhaustive book The Pirates And The Mouse: Disney’s War Against The Underground.

This great little short documentary recaps the Air Pirates saga and is a fine introduction to O’Neill’s fierce individualism. “You can’t have more fun than drawing pictures and pissing people off,” he notes right at the start.

Air Pirates is very smutty and funny stuff, but it’s still Odd Bodkins that made me a fan of O’Neill for life.

Odd Bodkins was a great intermediate step between “kids” comic strips like Peanuts to the wild weird world of the underground. The handful of old ‘60s and ‘70s collections have been reprinted by O’Neill and can be found on Amazon, although I think a huge chunk of his work has never been collected, which is a bit of a crime for underground comics history.

Weirdly, Dan O’Neill moved to the same town that I grew up in up in the Sierra Nevada foothills, although I’ve never met the man – alive and well and drawing scathing cartoons about Trump well into his 80s. It’s fitting he ended up in Nevada County, which as I’ve written is kind of a weird, wonderful place.

When I turned to drawing my own comics, O’Neill’s scratchy, anarchic spirit was definitely one of the many ingredients in the cosmic gumbo that made up my work. He showed me you didn’t need to be a master artist to make a difference, and that a unique point of view and a sense of humour went a hell of a long way towards making great art.

O’Neill has always pushed at the system, and found the funny in the chaos of the world. He blew my mind at a very young age and part of me has never quite been the same since.