Once upon a time a million years ago, your worth as a journalist was measured by your “clippings file.” It was your best interviews, your sharpest breaking news, your most erudite commentary, all painstakingly clipped from whatever newspaper/magazine you were published in, kept in a file, photocopied and sent off whenever you applied for a new gig.

That’s all jurassic-era stuff now, to be honest, and these days my “clips” are 90% composed of bits and bytes. My “clippings file” of recent work is basically just a link on this webpage, really.

But, because I’m an old hand in the business, I’ve got a hefty box of clippings that still, for some reason, I’ve carried around the world with me and which I periodically pull out once a decade or so to tidy up – some of the clippings now nudging past their 30th birthday.

When I first moved to New Zealand 18 (urk!) years ago many of these clippings seemed a bit more current, to be fair, and we were still moderately in a print-favourable environment for journalists then. You never know, a feature profile I wrote back in America might’ve been just the thing to impress a new boss.

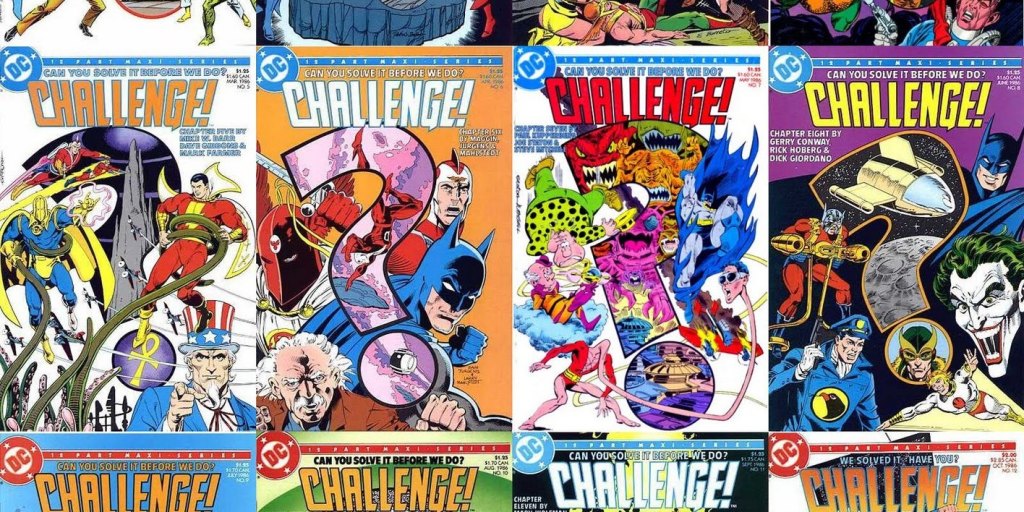

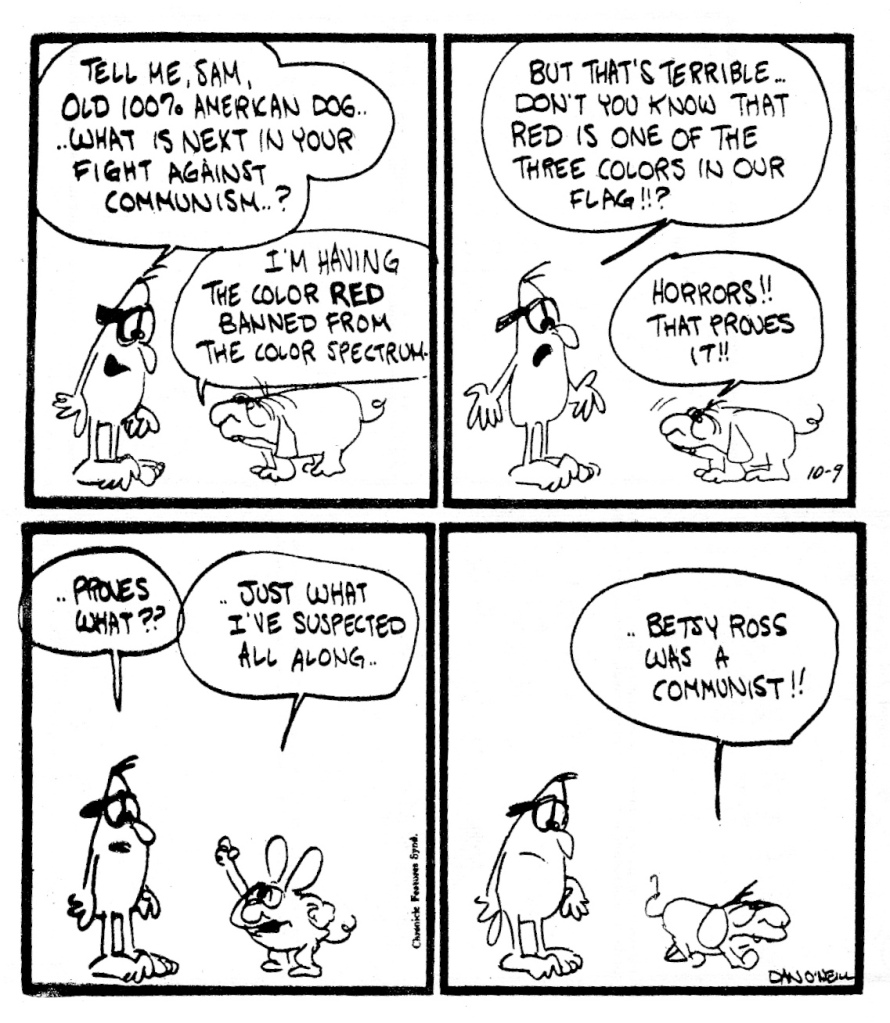

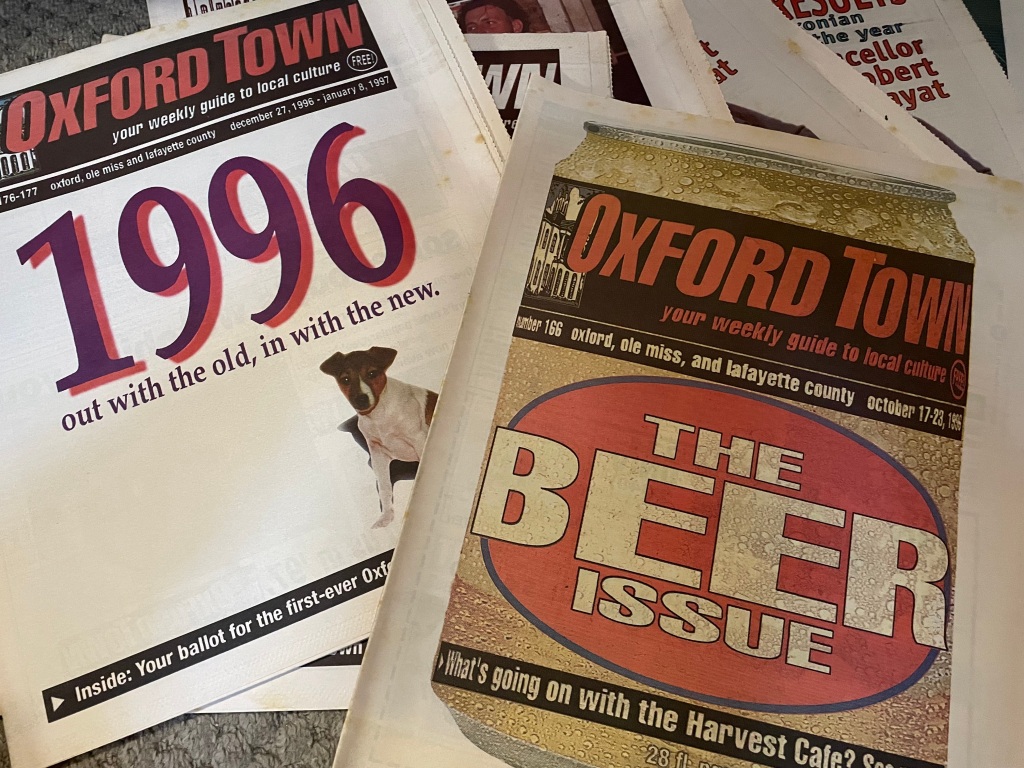

The box contains the very first paid journalism I did for The Daily Mississippian college paper 30 years ago now, like the time I interviewed California Gov. Jerry Brown (and accidentally stepped on his foot) or that time I had a daily newspaper strip. It contains more than 100 issues of the local “free alternative weekly” newspaper I worked at and then became editor of, Oxford Town. I kept all the issues I edited, because I still, 25 years on, remember every silly story, every goofy design choice, every snarky pun I tried to sneak past the publishers. You never love and hate a job quite like the very first job you feel truly good at, you know.

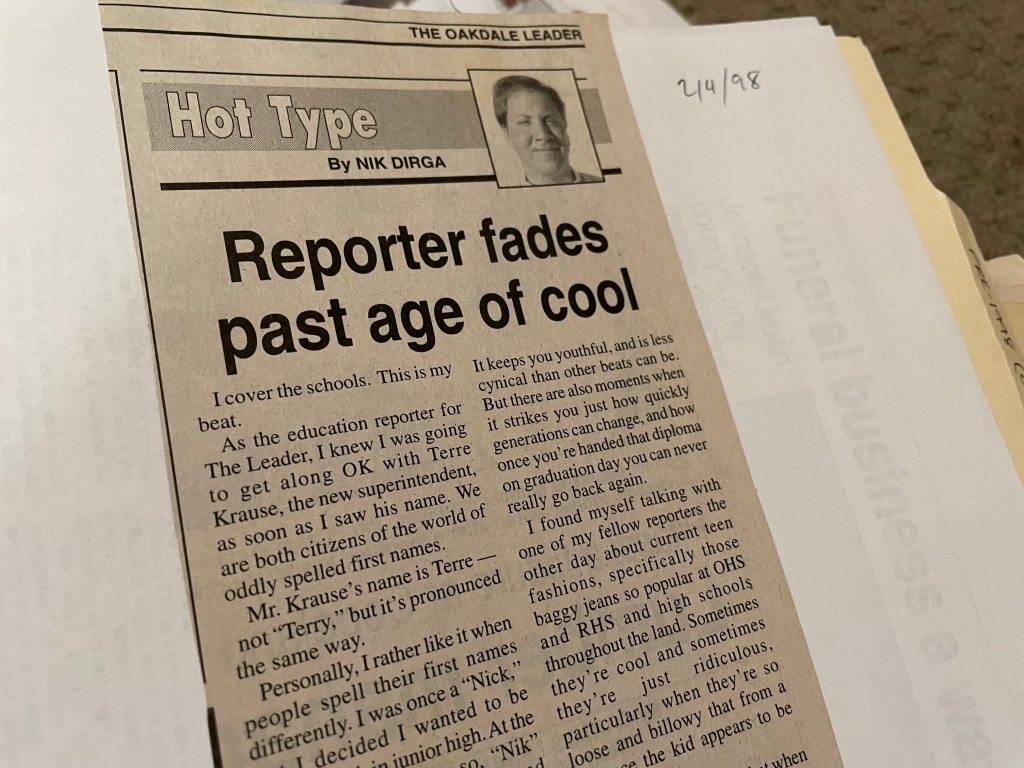

The box endures, newsprint archaeology of a so-called career through my college days in the 1990s and into the early 2000s, to a tiny newspaper in Oakdale, California where I lasted an anaemic 8 months, to the newspapers in Lake Tahoe I edited for years, to the great little paper in Oregon I worked at just after I got married and had a kid.

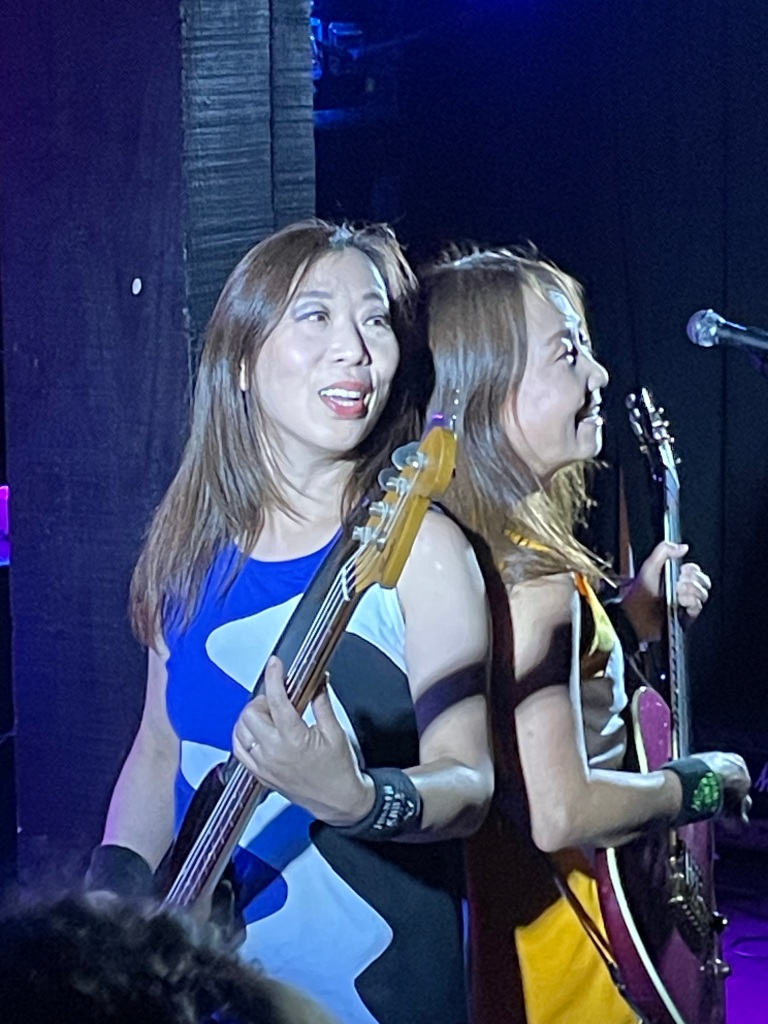

There’s feature interviews I wrote about Pulitzer-prize winning authors and Russian painters and zoo veterinarians and chocolate makers. There’s endlessly navel-gazing columns spanning my optimistic 20s and early 30s that I’m both kind of proud of and embarrassed by these days, lots of random music commentary, a long run of video review columns (hey! remember video stores?) and more. If you want to know what I thought of Terminator 3: The Rise of the Machines, the box is the place to go! Hell, there’s even a couple of journalism awards I won!

None of this is remotely useful to me in my alleged career these days, working as a digital journalist and factchecker and freelance writer and whatever the heck else it is I do in an industry that’s changed an awful lot in the 30 years I’ve been doing it. A lot of my writing was very of-the-moment stuff that matters little today. So I could just toss all of this stuff that’s gone from Mississippi to California to New Zealand with me.

But, still. If I throw out a newspaper I edited 25 years ago, that’s it. It’s essentially erased. There’s no website carrying most of its contents, no scanned repository of most small-town newspapers. Heck, even most newspapers unless they’re The New York Times barely have any kind of online archive past the last decade or so. Contrary to what sometimes feels to be the case, all of life isn’t online.

I can pare it down. I have no earthly reason to keep three copies of an issue of a newspaper I edited in 1997 that I was particularly proud of at the time, really.

The box is hefty and awkward and old-school, but even long after the ink has dried on those pages, it feels like it still means something, somehow. Journalists live by their words.

I’ll whittle the box down a little bit more again in this go-round, but will end up keeping most of it still, where it’ll end up in the back of a closet for another several years, a silent testament to the stories I once told and the deadlines I once met. Heck, maybe one day my son will inherit it and either treasure or trash it all.

You can just throw out the stories of your life, but why would you?