At this point, complaining about what a terrible year life has thrown at us is a bit of a cliche, eh? So yeah, bad things happened in 2025, oh boy did they … but if you try to doomscroll less and open your eyes a little more to everyday goodness, sometimes things can feel like they even out.

As always, the soothing balm of pop culture – a good book, a great album, a rad comic or a mind-blowing movie – helps make the world go down a little smoother sometimes. So, at the end of year in review week for me, let’s hopescroll, with the 10 best pop culture moments I had this year!

Amyl and Sniffers live at the Powerstation, February 16: This was not a very big year for live music for me, but I promised 2025 would be my year of punk rock because right now being a punk seems the best way to fight all this enshittification. Australia’s awesome punk rising stars Amyl and the Sniffers delivered a hell of a show, full of joyful rage and a reminder that not everyone has turned evil in 2025. They’ve already played to far bigger crowds this year than the cozy Powerstation, but I’m glad I saw ‘em when I did.

Superman saves squirrel: If you didn’t like this moment in Superman, what can I say? It’s the essence of Superman – he won’t even let a squirrel die if he can help it! and a welcome return to optimism after far too many grimdark Superman tales.

Pluribus: Breaking Bad creator Vince Gilligan’s apocalyptic new epic starring a fantastic Rhea Seehorn might be the year’s best television – full of fascinating worldbuilding and a methodical yet hypnotic pace – a welcome novelty in this era of endless distractions. While some armchair critics called it ‘boring’ because it didn’t feature Walter White blowing up stuff every episode, I don’t think they get Pluribus. It’s a unique vibe that leaves you thinking about what it really means to be human and part of humanity. I only hope it continues to pay off whenever Season 2 comes around.

The Pitt: Old-school and yet up-to-the-minute, this electrifying hospital drama was also a sharp reminder that despite all the endless glut of “content” flooding streamers with meandering plots, sometimes you can just pare everything back to good characters and plot momentum and score one of the best shows of the year.

That juke joint scene in Sinners, which floored me with its sheer beautiful audacity and confidence that the audience would keep up: “So true, it can pierce the veil between life and death.”

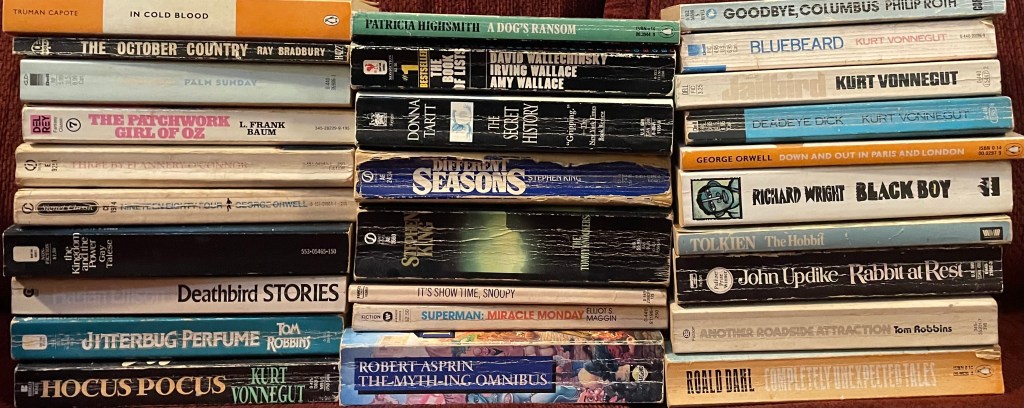

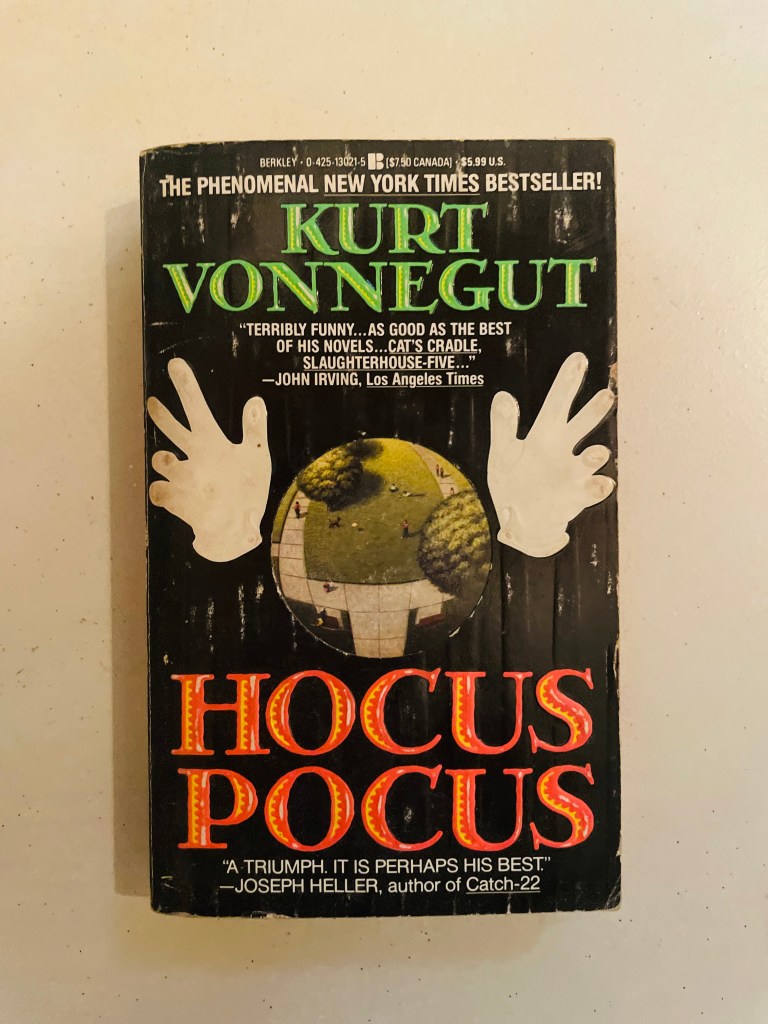

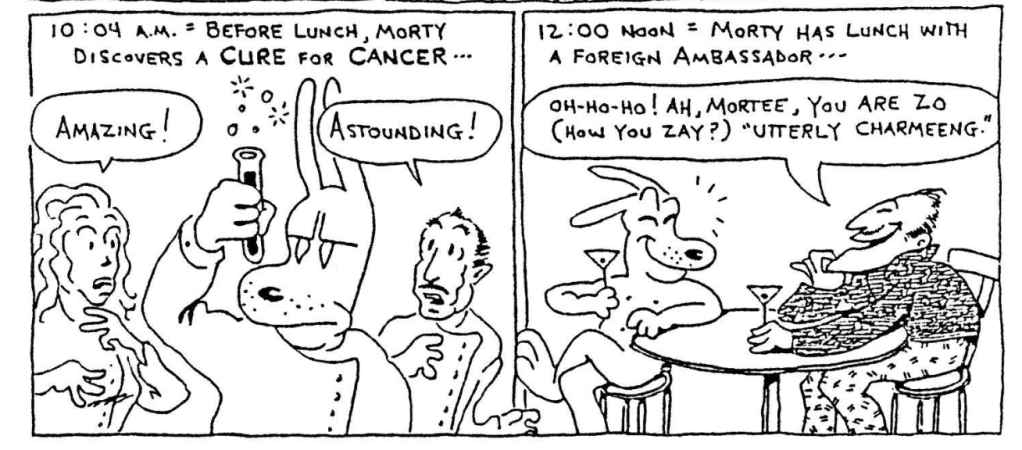

The Collected Cranium Frenzy by Steve Willis: One of the coolest little projects this year was a comprehensive reprinting of Cranium Frenzy, the surreal and hilarious small press comics of the legendary Steve Willis. Never heard of him? You should! As I’ve written in the past, Willis is absolutely one of the greats of the minicomics scene ever since the 1980s, but like most minicomics, it was literally impossible to find his work in print. Phoenix Productions have picked up the ball with five gorgeous little books collecting decades worth of work by Willis all on Amazon, well worth seeking out for the adventures of Morty the Dog and many more!

Wet Leg, moisturizer: I’m an old geezer whom Spotify now tells me is roughly 110 years ancient, but my favourite album by a “new” band this year was Wet Leg’s sprightly, sexy and hook-filled second album, a catchy fusion of alternative rock (does that still exist), post-punk, dance and whatever else you’d like. I’ve been humming along to “liquidize” for months. Be my marshmallow worm!

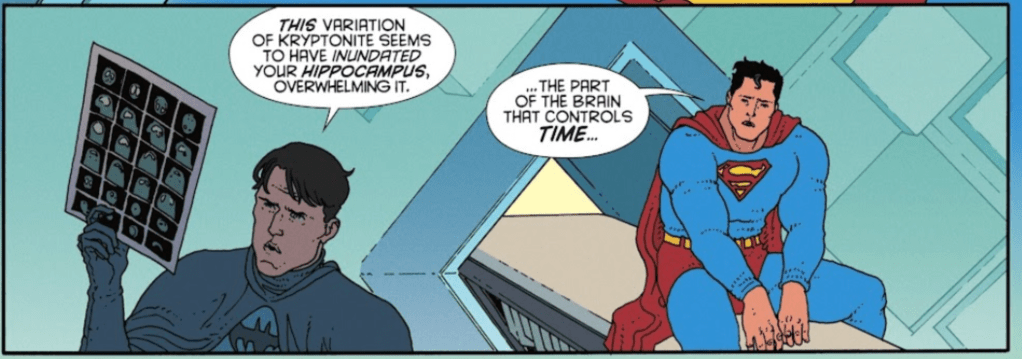

Superman: The Kryptonite Spectrum: A wonderfully quirky miniseries by Ice Cream Man creators W. Maxwell Prince and Martin Morazzo that embraces all the wacky insanity of vintage Superman comics and gives it a surreal spin, kind of like if David Lynch tried to write a Spider-Man comic. I’ve sampled Ice Cream Man and it wasn’t my thing, but this Superman miniseries is such a colourful “elseworlds” delight that I’ll be keeping an eye on these creators from now on.

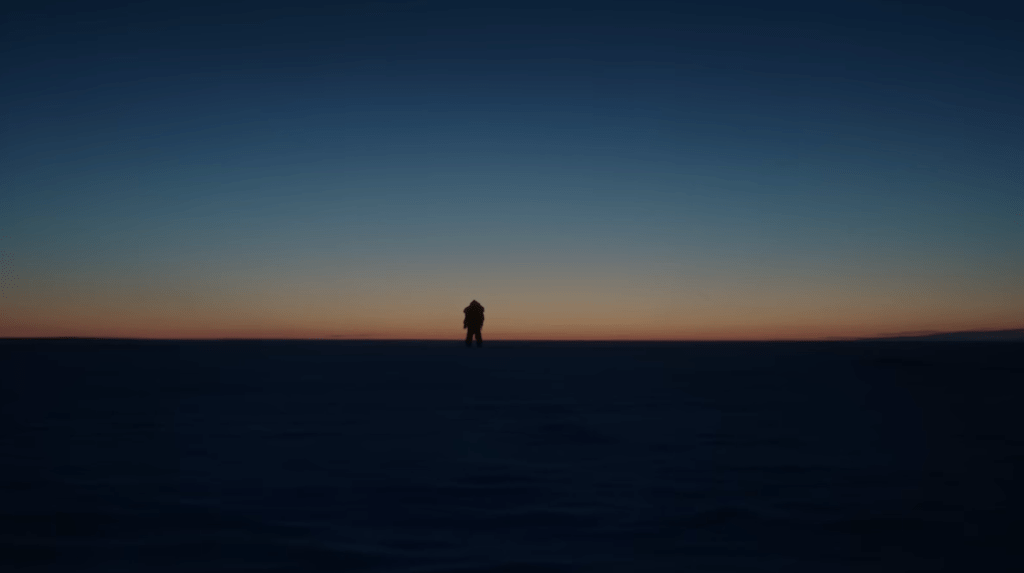

This one amazing shot in Guillermo Del Toro’s terrific Frankenstein:

Writing a book: I hit 30 years in journalism at the end of 2024 and decided it was time to put together a “greatest hits” of sorts of my columns, essays, articles and more. It’s a total vanity project but I’m really pleased with how Clippings: Collected Journalism 1994-2024 came out and the kind words by family, friends and even a few complete strangers who’ve bought it. It’s more than 350 pages of scribbles that somehow sums up my so-called career. Get it now over on Amazon (and you can pick up a few collections of my long running comic series Amoeba Adventures there too)!

Let’s all try to have a decent 2026!