Nobody made being a total bastard quite as funny as Rik Mayall.

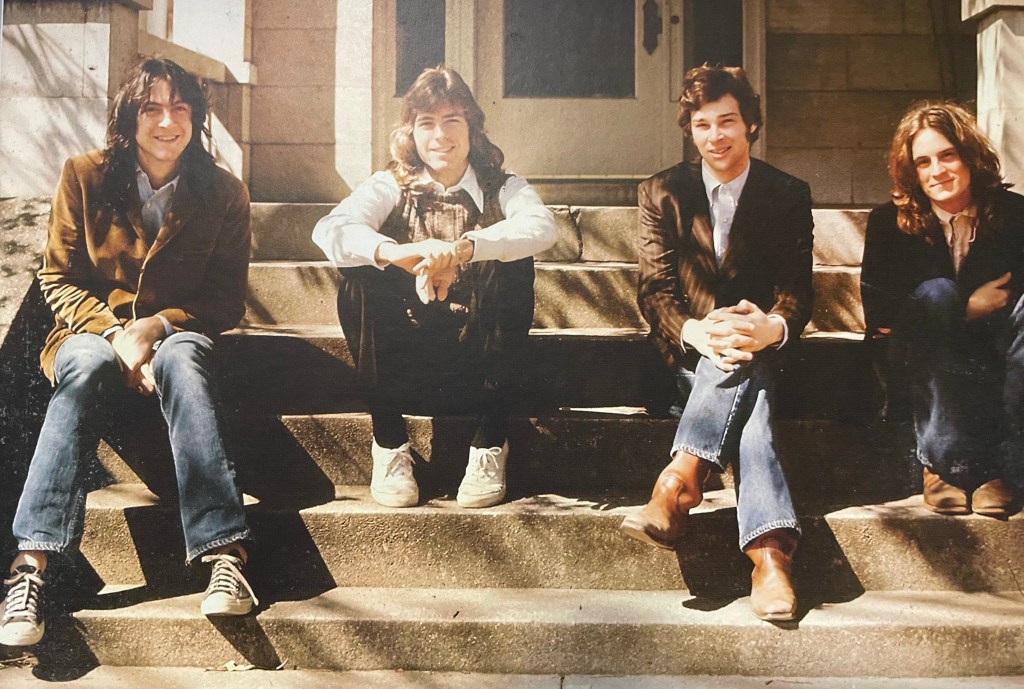

When I first stumbled on The Young Ones in the late ‘80s during its inexplicable MTV late-night airing in America, I felt like I’d seen into a different universe. The anarchic gang of college misfits were all hilarious, but to me, Mayall’s Rick was on another level of twitchy, ego-free energy, willing to make himself look as sweaty and horrible as possible for the gag. He bounced perfectly off Ade Edmondson’s ultraviolent punk parody Vyvyan.

Rik Mayall’s been gone 10 years now, a fact I still find kind of baffling. His comedy was so insanely energetic it seems impossible it should ever be stilled.

Mayall was the patron saint of comedy that combined ego and humiliation in equal measures.

Rick on The Young Ones was everyone’s worst nightmare of a pretentious, oblivious student, adopting pet causes left and right, constantly sure of his own righteousness and yet constantly trembling with his own self-hatred. You felt sorry for him but you also probably wanted to kick him right in his stupid face, too.

Nothing ever worked out for Rick, who hated everyone but hated himself the most. Mayall managed the extremely tricky wrangle of making this hilariously funny, a character who’s all twitchy id whether he’s trying to pick up “birds” at a party or insulting his roommates. Nobody ever spat out “Bastard!” quite as caustically as Mayall.

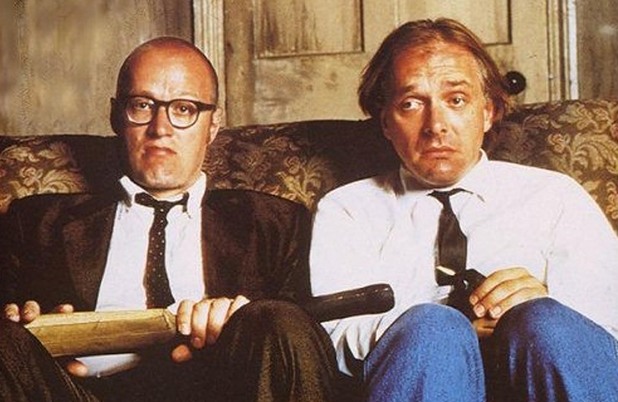

Later on, in their follow-up show Bottom, Mayall and Edmondson refined the Young Ones formula by narrowing in on losers Rick and Eddie, two gormless young men hurtling towards pathetic middle age. Bottom, as good mate Bob recently recalled in his own blog, is a masterpiece of over-the-top comedy, where every gag is pushed as far as it will go and then some.

Mayall and Edmondson smack each other around like a Looney Tunes cartoon, are consumed with unrequited lust for the opposite sex and their own sleazy poverty. I like to pretend that Bottom’s “Richard Richard” and Eddie are of course The Young Ones’ Rick and Vyvyan about 10 years on, youthful idealism and identities ground away and living lives of quiet desperation.

Later on, Mayall played the world’s most corrupt politician Alan B’stard in the witty satire New Statesman, and was great as blustery fool Lord Flashheart in Black Adder. He tried to break through in the US with the loud, antic cult comedy Drop Dead Fred, but it didn’t quite work – Mayall’s frantic man-child routine got grating quickly when stretched out to an entire movie.

At his best, Mayall played insecure, hateful guys who can never quite figure out that they’re their own worst enemy. It’s a marker of his talent that the creeps and bastards he played still felt ever so slightly loveable. When Bottom’s Richard Richard gets a well-deserved ass-kicking and then sits there ugly-weeping, who doesn’t feel a twinge? Maybe it’s just me. Losers are inevitable more entertaining than winners.

Rik was carried off by a heart attack in June 2014 at just 56. It’s probably the blackest of comedy to say so, but sometimes I wonder if that’s the way the Young Ones’ Rick, Bottom’s Richie and New Statesman’s B’stard all wouldn’t have gone as well, pushing their self-loathing energy until it burst.

I can still watch those episodes of The Young Ones and Bottom over and over no matter how many times I’ve seen them, and Mayall’s comic skill, working himself up into a sweaty red-faced mess to get a laugh, gets me every time. I only wish we’d gotten a little bit more of him.