My Beatles phase has never really ended.

Like all of us, I go through phases. One week I’ll be super-into the films of Billy Wilder, or I’ll be reading all of Percival Everett’s novels I can find or all of the Daniel Warren Johnson comics I can hoover up, and the next week I’ll be all about exploring the discography of Hüsker Dü.

But one phase that never really ends for me? That Beatles phase. Sure, it waxes and wanes, I might go a few weeks without listening to or thinking about the Beatles, but in the end, as the man said, I get back, get back to where I once belonged and dive back into figuring out the Beatles.

There’s been a flood of Beatles content lately, so I’ve been heavy in a Beatles phase the last week or two again – rewatching the terrific 1995 Anthology documentary for the first time in ages now that it’s made its way to streaming, and listening to the latest grab bag of odds ’n’ ends, Anthology 4, all while reading a very enjoyable new deep dive into the great Lennon-McCartney partnership, John & Paul: A Love Story In Songs by Ian Leslie.

The thing about the Beatles is, like anything that starts to pass into the realms of mythology, you never really get to the bottom of it all. I consider myself a 7 out of 10 on the scale of Beatlemania – I’m not one of those guys who can tell you who Stuart Sutcliffe’s grandparents were or what John Lennon had for breakfast the day they recorded “Penny Lane.”

There’s 213 or so “official Beatles songs” plus all the infinite demos, jams and alternate takes that have been pouring out the last few years in super fancy special editions. Recently I came back to the mildly obscure track “Hey Bulldog,” and really listened to it – the thumping piano intro, McCartney’s sturdy bass line, the giddy sneer Lennon gives the lines “What makes you think you’re something special when you smile?” It felt like a whole new song suddenly bloomed to me even thought I’m sure I heard it dozens of times before. How did this happen?

My parents weren’t big music listeners – about all I can recall in the way of “rock” music in the small vinyl collection was some Peter, Paul and Mary – so I didn’t really start hearing the Beatles in childhood, but I was the perfect age to discover them when their albums first started coming out on CD during high school and Generation X got Beatlemania. The Past Masters collections in particular cracked my head open navigating the band’s stunning evolution from poppy singalongs to psychedelic freak-outs. I still can’t quite fathom how they went from singing “Love Me Do” in the Cavern to recording “Tomorrow Never Knows” in less than four years.

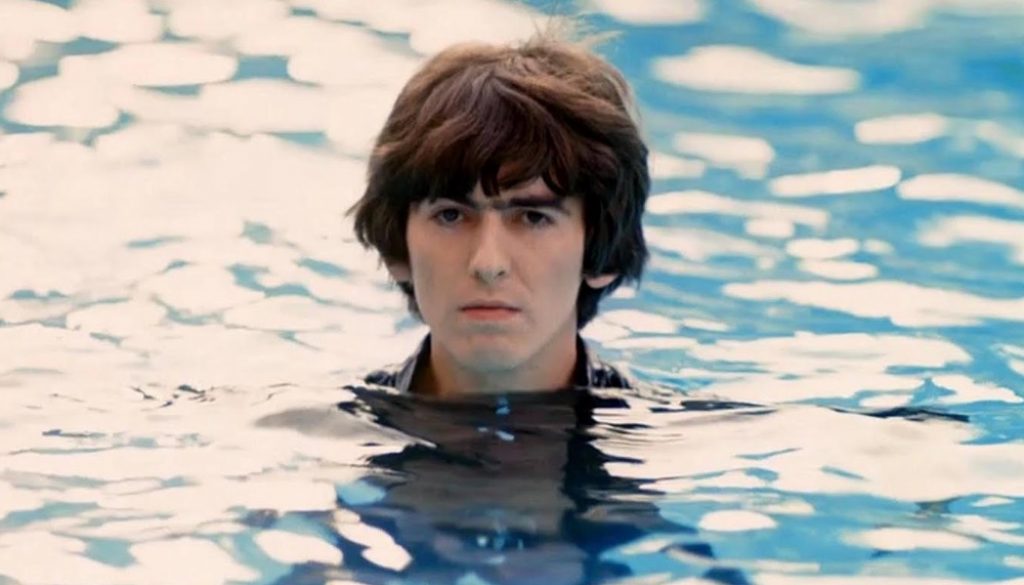

There’s a spark of joy that ignites in me whenever I truly listen to the Beatles, and I think the central mystery at the heart of it all is how these people, these scruffy rough kids from Liverpool, exploded to change pop culture in their decade or so of existence. We want to get inside these songs, to find how creativity itself works. The magic of creation remains the greatest magical mystery tour of all, and in an age where we’re increasingly served up algorithmic bait, fluff and trivia, the rough-hewn analog invention of Paul, John, George and Ringo still feels bottomlessly appealing to me.

This is why I never really end my Beatles education, because even a bit of a cash grab like the fourth Anthology collection, with its surplus of pretty rote instrumental tracks, can grab me by digging up the gloriously unhinged take 17 on “Helter Skelter.” I sucked up the unabashed nostalgia of “Now And Then” and I dug the rhythmic hypnotic excess of Peter Jackson’s sprawling Get Back miniseries.

I’ve listened to Abbey Road or Revolver a hundred times a hundred times over the years and yet I can still find tiny new scraps of newness in those well-worn grooves. Yep, like everything else, the Beatles have become a content-churning factory in 2025, and, that new “final” ninth episode of Beatles Anthology probably wasn’t truly necessary, yet the little fragments we get of 50-something Paul, George and Ringo (30 years ago!) jamming and messing about with John’s sketchy demos on “Free As A Bird” still feel true despite the glossy sheen of Disney’s content farming.

And so it’s gone, over the years – I keep coming back to the Beatles, and discovering how much I still haven’t really paid attention to before.

The very last words Ringo sweetly says as the nine-hour journey of Anthology winds down are, “I like hanging out with you guys.” Me too, mates.