Frankenstein’s Monster is dead, but he’ll also really never die.

I love it when a character hits the cultural level of a Sherlock Holmes or a Batman, and can be endlessly reinvented for new eras.

Maggie Gyllenhaal’s The Bride is the latest reimagining of the bones of Mary Shelley’s tale, a wild, anarchic creation myth and love story. It’s as loose and freaky as major Hollywood productions ever get these days, and while it’s sure to be divisive, I kind of loved it.

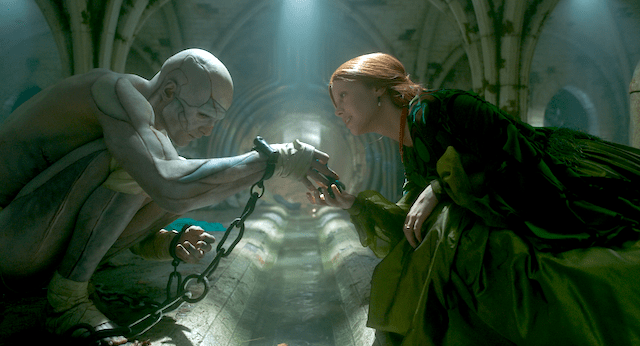

Very loosely retelling the events of Bride of Frankenstein in the 1930s, Oscar nominee Jessie Buckley gives a delightfully unhinged performance as a new “Bride” to Christian Bale’s wounded and lonesome Frankenstein’s monster. The Bride at times feels as rough and patched together as the monster himself, but that’s what charmed me – it tells something new by stitching together ghostly possession, a screwball musical, a blood-spattered romance and a Bonnie and Clyde-style violent lovers on the run arc.

The monster and his bride tear through polite society, and while the plot is sprawling and doesn’t always add up, terrific turns by Bale, Buckley and Annette Bening as this movie’s “mad doctor” work well. A truly insane homage dance number to Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein is the most audaciously strange scene I’ve seen so far this year. This one’s for the sickos, and I’m proud to be among them.

I’m here for all the Frankensteins, to be honest, right on down to campy ‘60s kaiju romp Frankenstein Conquers The World and the ultra-sleazy Frankenhooker.

There remains endless potential in the story of man creating life, and how it (usually) all goes horribly wrong.

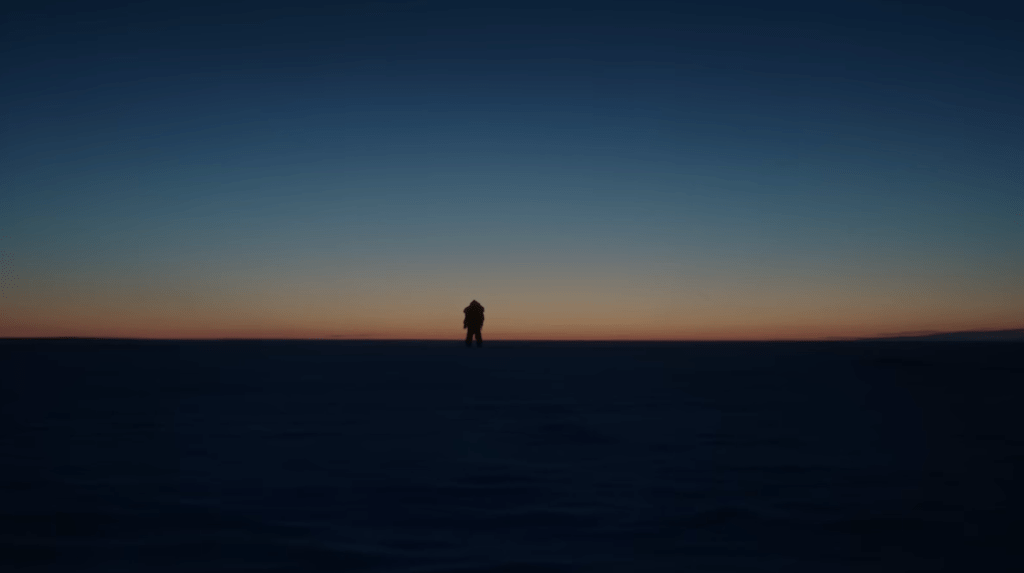

We’re only a few months from the last great Frankenstein movie, Guillermo Del Toro’s Gothic Oscar-nominated epic of an adaptation of Shelley’s novel with a committed and curiously sexy performance by Jacob Elordi as the monster. That one is as overwrought and passionate as The Bride, but in a completely different way. Those great lonesome Arctic chase sequences – always my favourite part of the original novel – sparkle on the big screen.

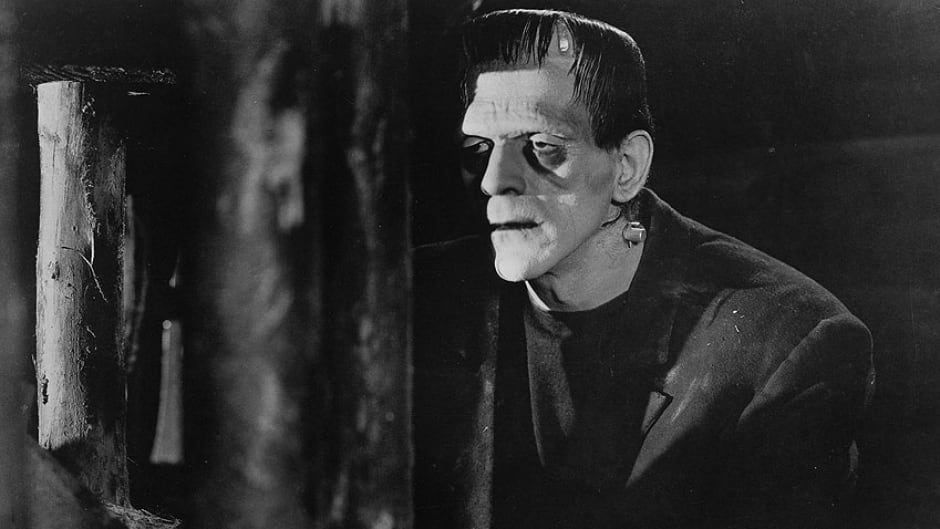

A rough Google estimate tells me there’s been close to 500 spins on the Frankenstein story. Boris Karloff set the standard, of course, and his performance, closing in on a century ago now, remains the template for investing the monster with both humanity and menace. Christopher Lee played the creature as a hurt, abused animal, with melting-egg makeup that seemed startlingly grotesque in 1957’s Hammer production The Curse of Frankenstein – then followed by a half-dozen more Hammer movies that totally reimagined the creature’s story each time, even as a woman and once as a New Zealand wrestler with the world’s worst makeup job.

Every era has its Frankenstein – splattery gore from Andy Warhol in the ‘70s, kid-friendly spoofs like The Monster Squad in the 1980s, bombastic excess like Kenneth Branagh’s 1990s take. I like the weirder angles, like Roger Corman’s Frankenstein Bound from 1990 that throws time travel and metafiction into the mix.

I’m even fascinated by the schlocky look of 1910’s Frankenstein by Edison Studios, the first adaptation of the creature’s story done in a mere 16-minute silent film, with Charles Stanton Ogle as a shaggy, deformed monster that’s memorably bizarre. A mere 116 years old now, it’s more of a curio than a successful film, but it sets the template for many a Frankenstein story in the century-plus since.

And that doesn’t even get into the non-film realms, like DC Comics turning Frankenstein’s monster into a kind of immortal holy warrior, queer fiction imaginings like Jeanette Winterson’s Frankissstein and the novel and movie of Gods And Monsters, or modern-day parables like Ahmed Saadawi’s Frankenstein in Baghdad.

The Bride builds on all these flocks of Frankensteins, and Gyllenhaal’s weird delight of a film embraces the shimmering fluid identities of the monsters – her romantic duo are alternately enraged and peaceful, needy and fiercely independent. I expect The Bride is the kind of movie a lot of people will hate, and it’s certainly not flawless, but it’s brave in its own weird way.

For a book that came out 208 years ago, Shelley’s Frankenstein is still remarkably futile ground for birthing all kinds of stories about mankind’s hopes and dreams, and nightmares.