You know, I love the Ramones a little more every day, and their molten-punk purity of just bashing out pop tunes as fast they could. They weren’t fancy – they were anything but – but they hit on some elemental force that they turned into a 20-plus year career.

Back in 1979, legendary producer Roger Corman and director Allan Arkush somehow thought the Ramones would be the perfect band to anchor a classic teenage rebellion musical with a warped underground edge. Rock ’n’ Roll High School is a campy screwball delight even now, a time capsule of leotards and neon fashion in that cusp of an era where disco, punk and new wave all scrambled for cultural relevance.

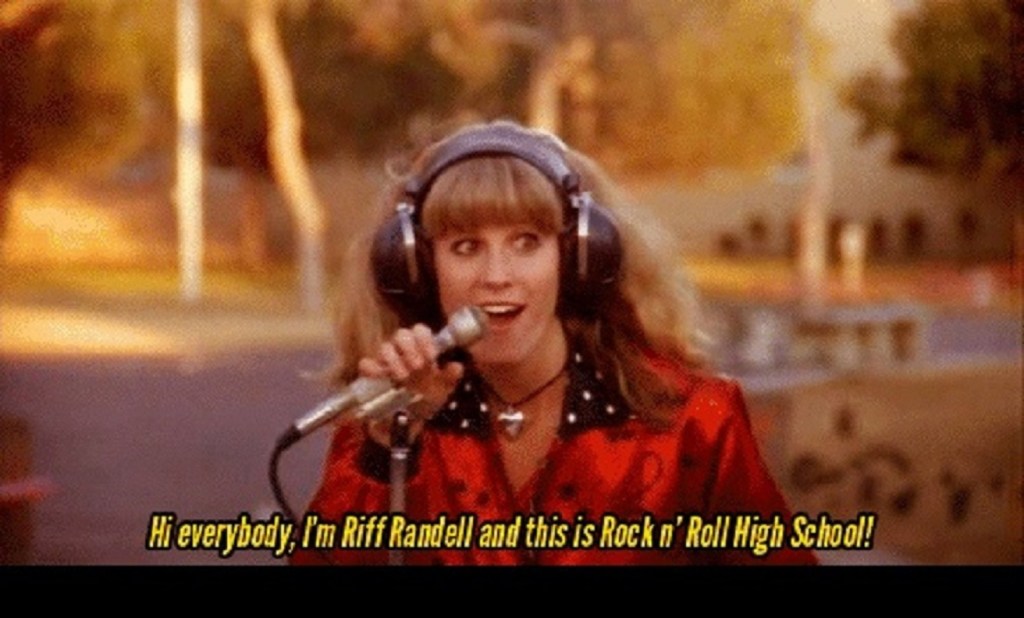

PJ Soles is Riff Randell, a perky punk fan with a heart of gold who’s the Ramones’ biggest fan, while her best friend Kate is a nerdy good girl with a crush on football player Tom. When the no-nonsense new Principal Togar (the wonderful Mary Woronov, veteran of Andy Warhol movies and much more) comes into town, it all sets up your classic clash between teens and authority.

It’s a wonderfully sincere little punk rock movie, with Soles’ chipper enthusiasm jostling with Woronov’s sexy dominatrix vibe. It lacks the meanness of a lot of teen movies (for comparison, I watched 1984’s Revenge of the Nerds for the first time in decades the other day, and hoo boy that hasn’t aged well). Even the handsome football jock in this movie is kind of a decent guy, despite being an utter horndog. The kids in this movie mostly look like real kids rather than 30-year-old cosplayers, and it’s filled with great character actors like Clint Howard and Paul Bartel’s stiff music teacher who, of course, loosens up and gets down with the punkers.

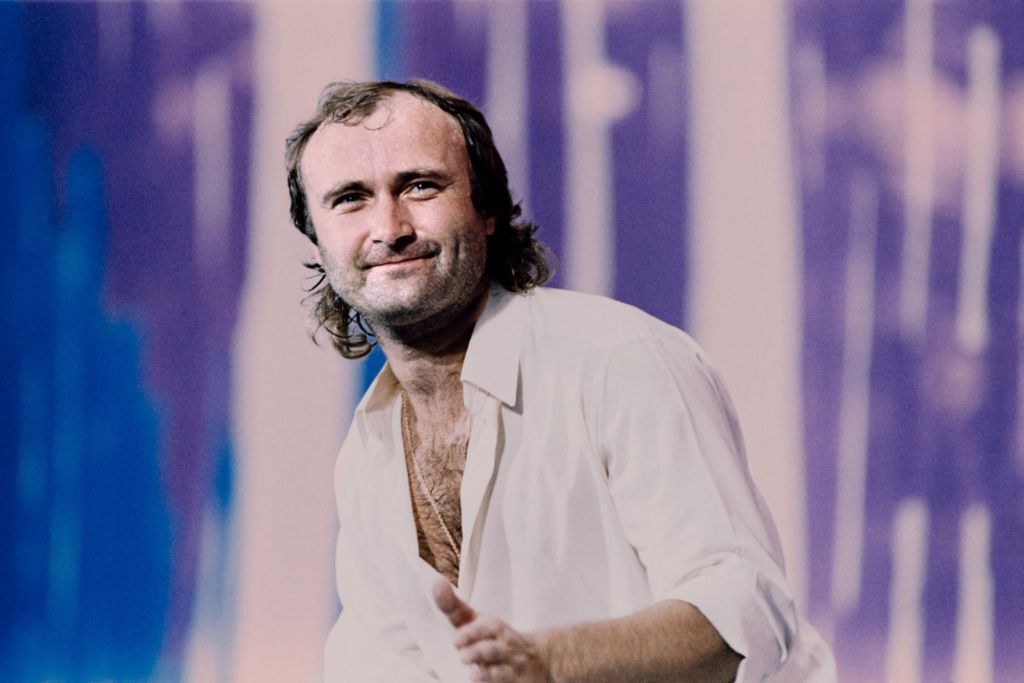

And when the Ramones rock into town, they’re like a blast of sleazy adult energy that still manages to feel cartoony.

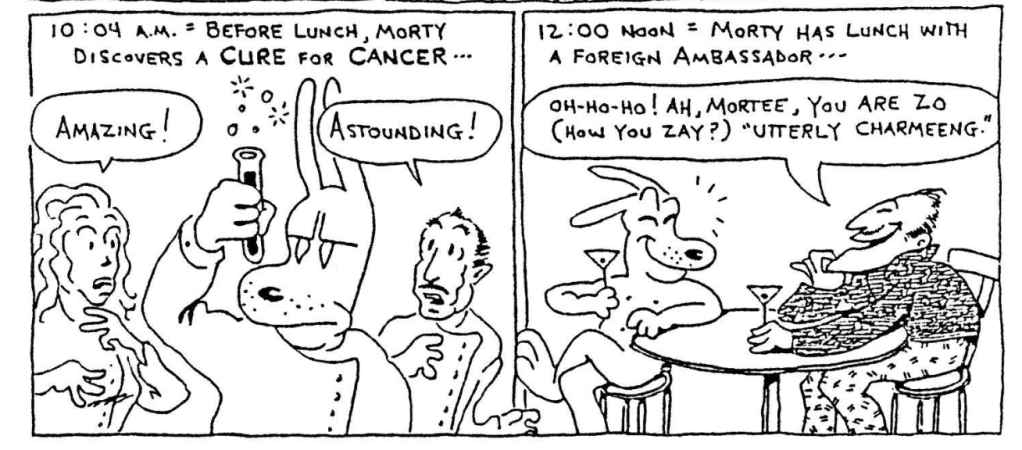

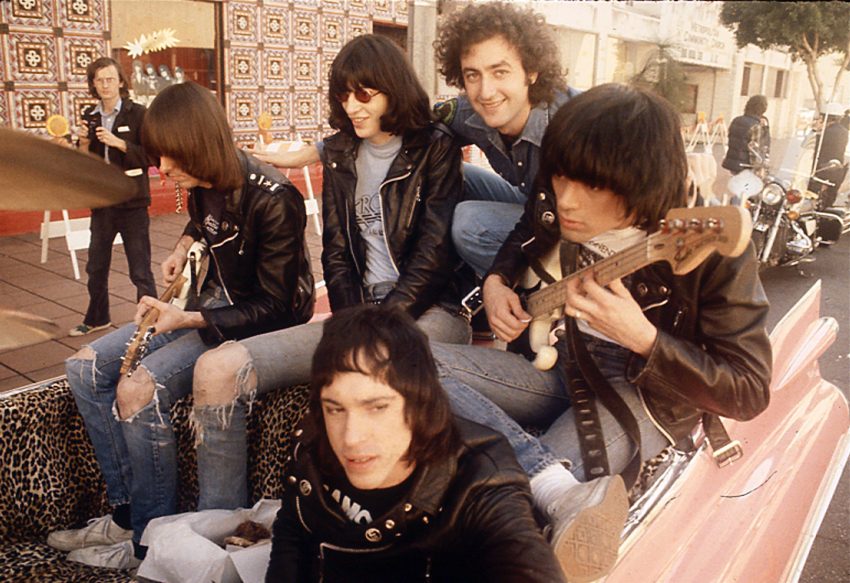

One of the beauties of Rock ’N’ Roll High School is just how weird the Ramones are on screen. They don’t appear until around halfway into the movie, riding down the street in a groovy Ramones-mobile and looking like they just fell out of a comic book, a leather-clad blast of menacing charm.

The Ramones seem rather uncomfortable shoehorned into this teen comedy, and yet, it all works – they’re an intrusion from another world, and you can’t take your eyes off them. Joey, in particular, was all awkward angles and bulbous features covered by a mane of hair and those ever-present dark glasses, and he looked a bit like a scribbled rough draft of a rock star come to life.

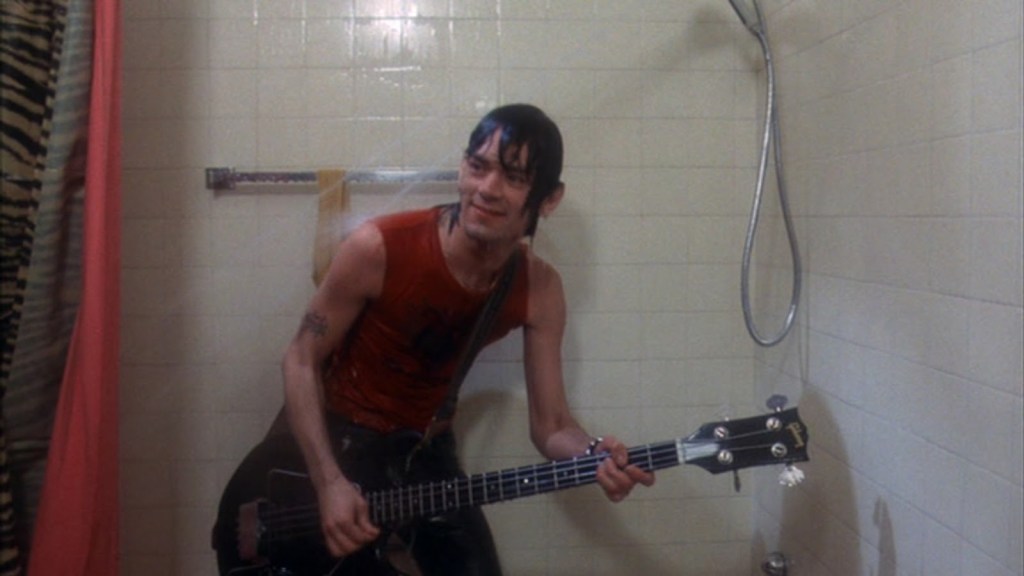

The movie’s best scene is a barely-disguised masturbatory fantasy by PJ Soles of the Ramones playing in her bedroom, capped with Dee Dee revealed to be playing in her shower! I love the darned Ramones, but picturing them as Elvis-type sex symbols feels like a stretch. Did they ever even take off those leather jackets, anyway?

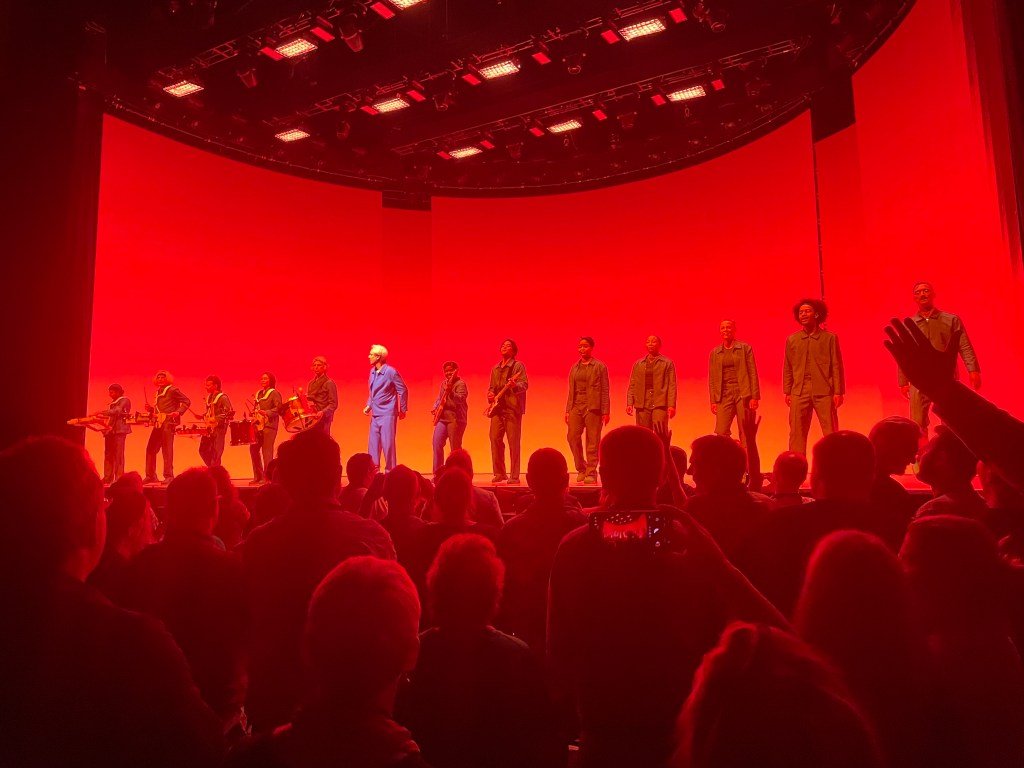

The Ramones couldn’t really act worth a lick – most of them barely have lines in the movie, and when they do they sound like the raw amateurs they were at doing anything other than punk rock. A highlight of the film is simply watching them in concert blasting through numbers like “Blitzkreig Bop,” “Teenage Lobotomy” and “Pinhead” and the title song.

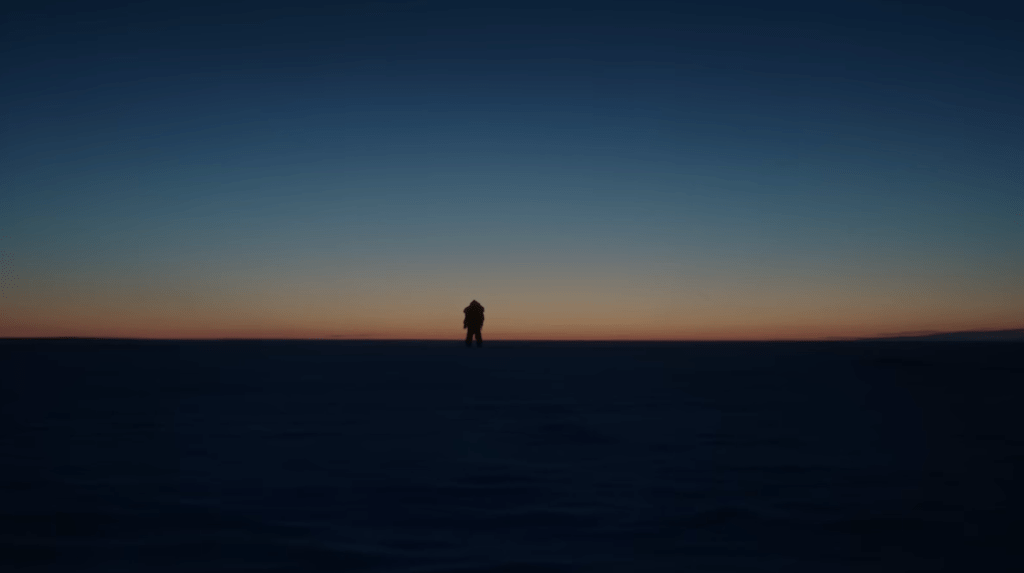

In real life, they were troubled, of course – only one of the band made it past his early 50s, and Joey, Johnny, Dee Dee and Tommy are all long gone now. The Ramones blazed through the culture like one of their songs, and I’ll always regret that I never saw them live.

By the time the Ramones show up at the high school and tear it all up in a furnace of punk petulance and a literal explosion, it’s cathartic as hell, even if you didn’t mind high school all that much. Take that, Principal Togar and all the jerky fascist authority figures in this world who think they know what’s better for everybody else. (Um, I might just be projecting about life in the year 2026, a little…)

Amusingly, the behind-the-scenes on the blu-ray talks about how the movie almost came to star other bands – such as Van Halen or Devo (can you imagine?).

Yet it’s the Ramones, who got so much out of a handful of chords and lyrics about freaks and fumbling love and sniffing glue, who were the perfect fit for this subversive take on teen musicals. Their presence captures the alchemic power a great rock song can have in your life, the way it feels like it blows down the doors of your boring reality and hurls open the doors of infinite potential. Yeah, even if they’re just singing about how Sheena is a punk rocker.

As both a time capsule and a kind of warped Bizarro version of so many other far worse rock ’n’ roll teen movies, Rock ’N’ Roll High School has strangely endured, closing in on 50 years now. It’s a blast of pure weird joy that makes the world feel a little bit better every time I watch it. Gabba gabba hey!