Cameron Crowe’s Say Anything is a great movie and one of the best teen romance movies ever made – quirky yet sincere, witty yet honest. John Cusack’s Lloyd Dobler and Ione Skye’s Diane Court feel real in a way so many ‘80s teen movies never manage to. I saw it at least three times in the theatre back in 1989 when I was deeply underwater in my own series of doomed high school love affairs and I love to revisit it in the years since.

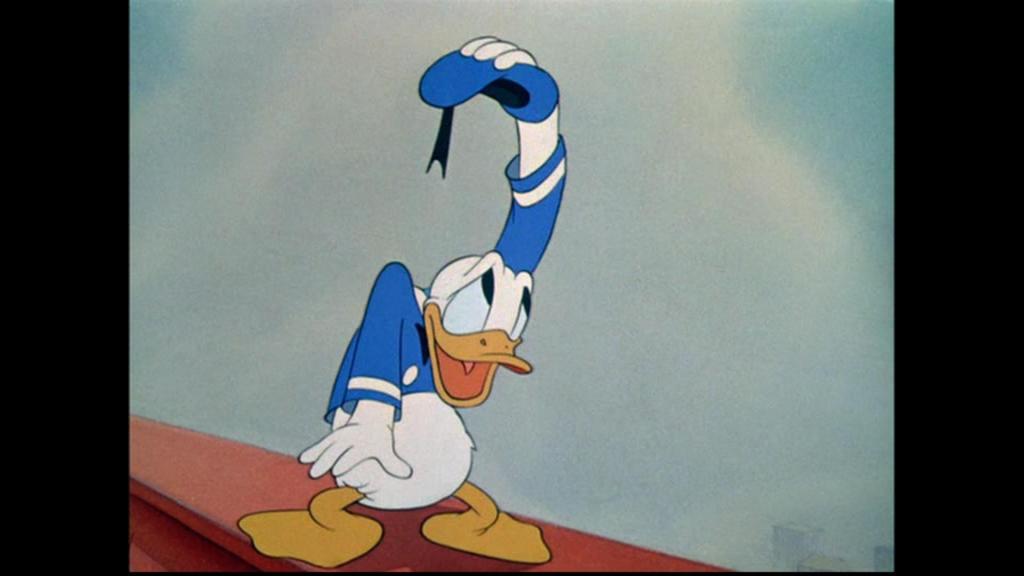

And yet – I think just about my favourite little moment in the movie, even more than that whole iconic boombox scene, isn’t anything to do with teen romance at all.

Instead, it’s Diane’s father Jim, played by the late great John Mahoney, singing alone in his car off-key along to Steely Dan’s “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number” just before his life is about to fall apart.

Poor old Diane’s dad has been defrauding the rest home he manages and will soon be arrested, and it’s a tragic little twist in the movie that the father she idolises turns out to be an inept con man. At this point, Jim probably knows there’s bad things coming, and they do, but just for a moment, he’s in a car and Steely Dan comes on the radio and that’s everything.

Diane’s dad sings happily along with Steely Dan with all his heart, not caring that he sounds awful, but the music has snagged something deep inside of him and it won’t let go. Sometimes a song gets you like that, usually when you’re alone, and you feel it pulling you inside whether you want it to or not. I have a frickin’ awful singing voice, but sometimes you move on sheer primal instinct.

Music hits on a different level than most things, and it can break you open in new ways when you least expect it.

A song by the great Neutral Milk Hotel came on Spotify while I was out exercising a year or so back, and Jeff Magnum’s strained and aching voice hit me hard, bringing to mind all the love and loss we go through and the things we just can’t fix. Almost unconsciously I started singing along with “In The Aeroplane Over The Sea” and damn it, the lines “How strange is it to be anything at all” got me suddenly choking up in the middle of a suburban walk, sucked in. It felt wonderful and painful all at the same time, in an inchoate way I can’t even fully explain.

Or the other day that ‘80s chestnut “Head Over Heels” by Tears For Fears came on and for some reason this time the chorus got me, and I began singing along alone in the car, ecstatic and sad and nostalgic and hopeful in all the ways a good song can unearth in you. And don’t even get me started about Peter Gabriel’s “In Your Eyes” also featured so prominently in Say Anything… that song contains entire multiverses for me.

There’s a part of everyone that sometimes is just like Lloyd Dobler’s girlfriend’s dad, singing along by yourself about Rikki, hoping she doesn’t lose that number, knowing she probably will, but maybe she’ll send it off in a letter to herself.

There’s a beautiful loneliness to Jim Court’s car singalong, but there’s also the music, keeping him company and for just a few seconds, making everything all right again.