I’m not a violent man. I’ve been in like three actual fights in my life, and think I lost 2.5 of them. But I do love a good ass-kicking on the screen, the weird poetry of movie violence.

In the pandemic era, there’s been no steady flow of blockbuster superhero epics and action flicks to look forward to. So I’ve been spending an unseemly amount of time diving into the past in search of an adrenaline fix, and eventually asking myself: Can one watch too many kung-fu movies?

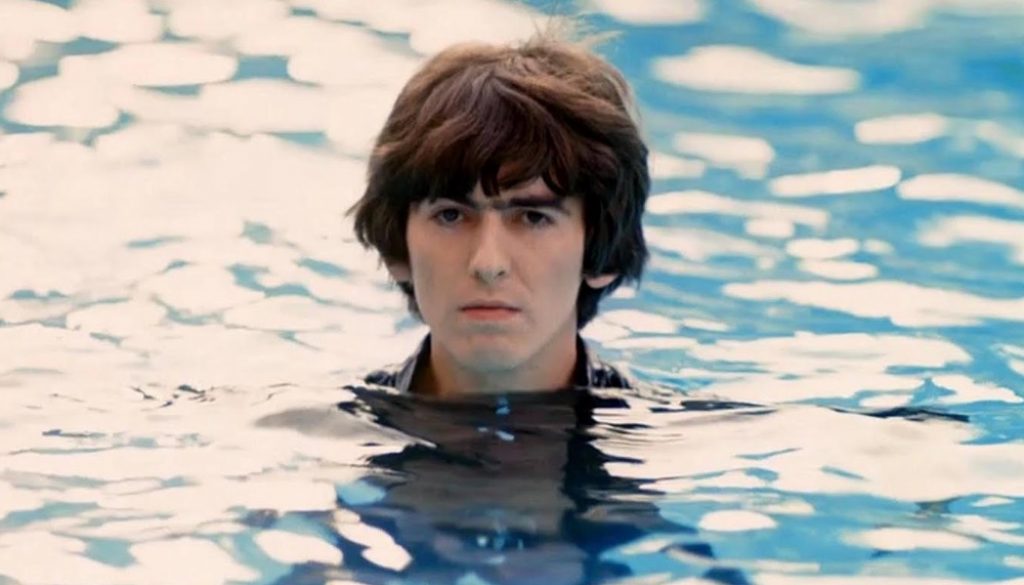

I dig a good flying kick to the face, and have long loved the acrobatic chaos of Jackie Chan or the slick killer grace of legendary Bruce Lee. The scarcity of cinema visits and new movies to watch the last year or so has led me to dive even deeper into the wonderful, wacky bottomless world of martial arts cinema, a true “shared universe” of peak human suffering and mythological endurance, where men are battered, beaten and rearranged into new shapes without the benefit of CGI. There are literally thousands of movies churned out by Hong Kong and other studios in the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s, and for every gem I’ve seen I discover another half-dozen I haven’t.

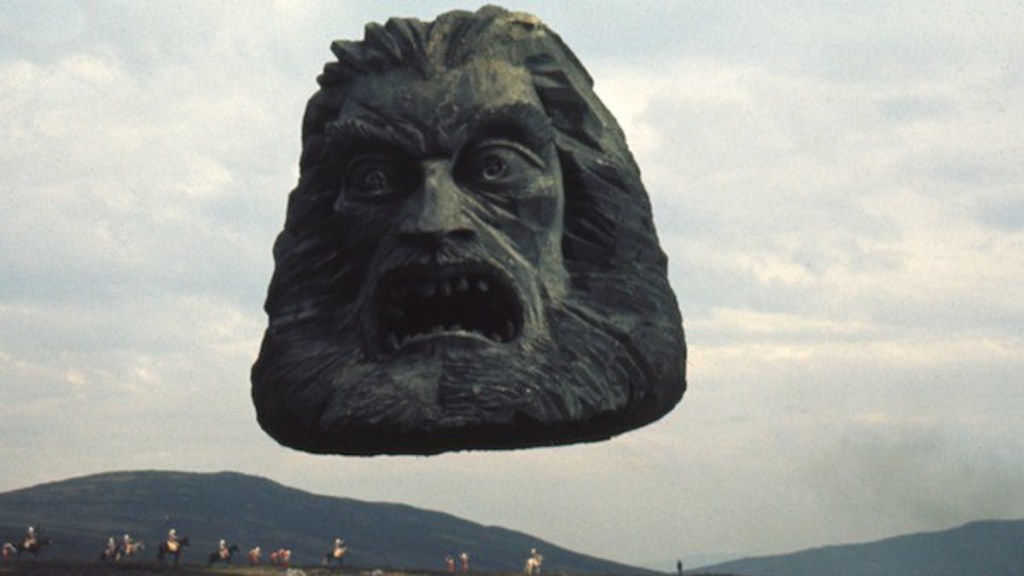

There’s something visceral and exciting for me about seeing that Shaw Brothers studio logo opening up a film, a sign that the story ahead will provide epic action and mythic storytelling — maybe not so much character development or realistic human interaction but hey, that’s not why we’re here. Betrayal, vengeance, revenge and redemption – that covers the vast majority of themes, dressed up with an infinite number of brutal actions.

I slid into the habit of watching more and more kung-fu flicks in recent months as a remedy to the chaos of the outside world – here, all problems can be solved by a good backwards kick-flip.

I drank in more classic kung-fu movies I’ve long meant to see, like The Prodigal Son, with Yuen Biao and the wonderful late Lam Ching-ying in one of the best zero-to-hero storytelling arcs; Sammo Hung’s hilarious bulky grace in The Magnificent Butcher and other films, the bloody King Boxer/Five Fingers of Death with its ripped eyeballs and music so memorably sampled by Quentin Tarantino; endearingly awkward Jimmy Wang Yu’s One-Armed Boxer and One-Armed Swordsman; the immensely creepy Mr. Vampire with its gloriously weird hopping “jiangshi” Eastern-style vampires.

More recently, there’s the amazing work of Donnie Yen in films like the awesome Ip Man series and insanely intense battles in Kung Fu Killer or SPL (Kill Zone). Yen combines Clint Eastwood’s stoic Man With No Name allure with a dazzling speed and grace that’s made him one of the most exciting action heroes to watch perform in ages.

Not every martial arts movie is equal – the attempts at humour in many “kung fu comedies” is often very broad, dated and sexist and too frequently, rather rapey for my tastes. The cheaper and goofier the movies are, the more raw and silly the experience. The cheapest kung-fu flicks like this massively fun bargain-basement box set I got a while back are watched more as archaeological experience than anything.

Still, as much as I love these movies, one can overdose. When I start imagining everything in subtitles and every interaction involving duel of honour kicks and punches, I’ve got to back off sometimes and watch something which features actual human beings having actual conversations. The heightened, performative world of martial arts movies is such a self-contained world that it’s a shock to the system to see people in another movie going out to dinner without tables being overturned and bodies flying over the buffet. The pleasures of a good kung-fu flick are endlessly simple joys for me, but it’s never good to dine too much on just one thing. You can’t live on potato chips alone.

When I find myself with idle images of Jackie Chan somersaulting over furniture or Donnie Yen working the wing-chun dummy dancing in my brain at bedtime, it’s a sign to back off a little bit. But I always know I’ll be back, primed for yet another tale of endlessly acrobatic human beings and the damage they can do.