It took me 46 years, but I finally got my ROM toy.

As young fanboys turn into old geeks, we often fantasise about the childhood toys we once had, or the ones we never had at all.

I’ve written before about how addicting action figures could be and how, despite being a bit more flush of cash than I was when I was 11, I try to be a little more restrained these days. I’ll still buy one here or there, but they have to be special.

Like ROM.

Growing up in the late 1970s I was a vagabond child, and spent much of my eighth year travelling in a campervan in Europe with my family. I’d see comic book ads for things like Micronauts or Shogun Warriors or those new-fangled Star Wars action figures but I sure as heck wasn’t going to find them in Luxembourg or wherever the heck we were that week.

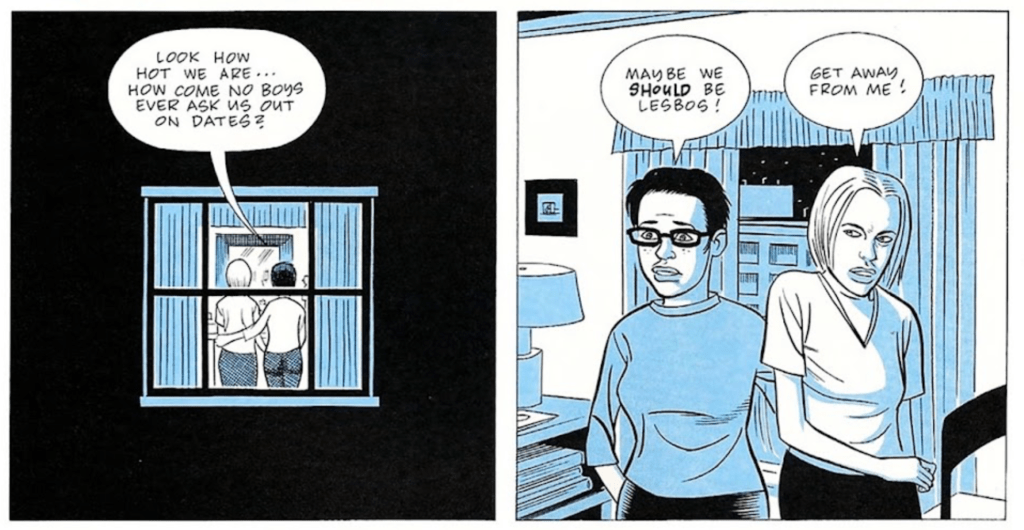

We couldn’t get a lot. One toy my parents got me somewhere in Europe which sounded cool was the Amazing Energized Spider-Man (TM) with web-climbing action, who rather lamely turned out to be an utterly immobile statue of Spidey with a perpetually raised left arm, who would get hoisted up by his little energized web winch thing. It wasn’t terrible, but there wasn’t a lot you could do with a Spider-Man toy who always looked like he was hailing the cross-town bus.

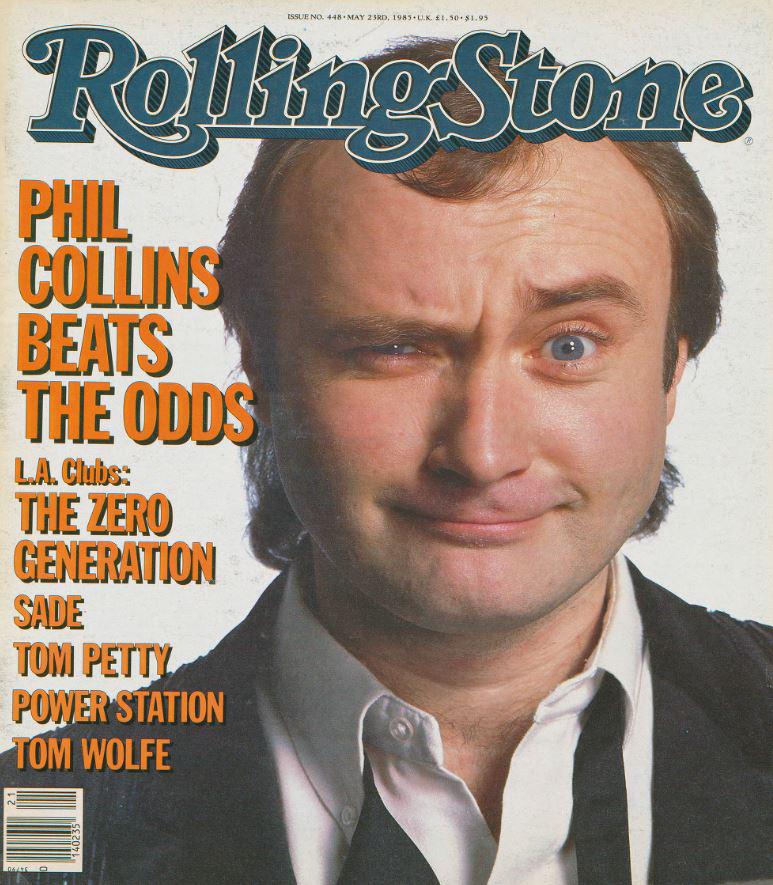

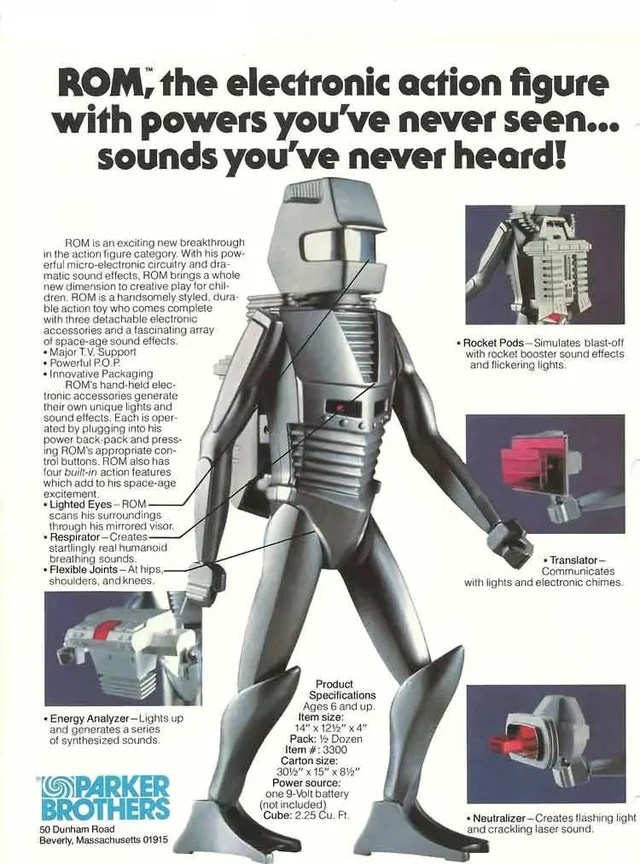

But one enticing toy I kept seeing in the American comic books I foraged from military base PXs in that distant world of 1979 was ROM. The ads blared, “ROM HAS COME … EVIL IS ON THE RUN!”

The ad boasted of “the greatest of all spaceknights”, who was premiering in a cunning case of cross-synergy with an electronic action toy by Parker Brothers and a new Marvel comic book series. Who was ROM? Heck if I knew, but I wanted to know.

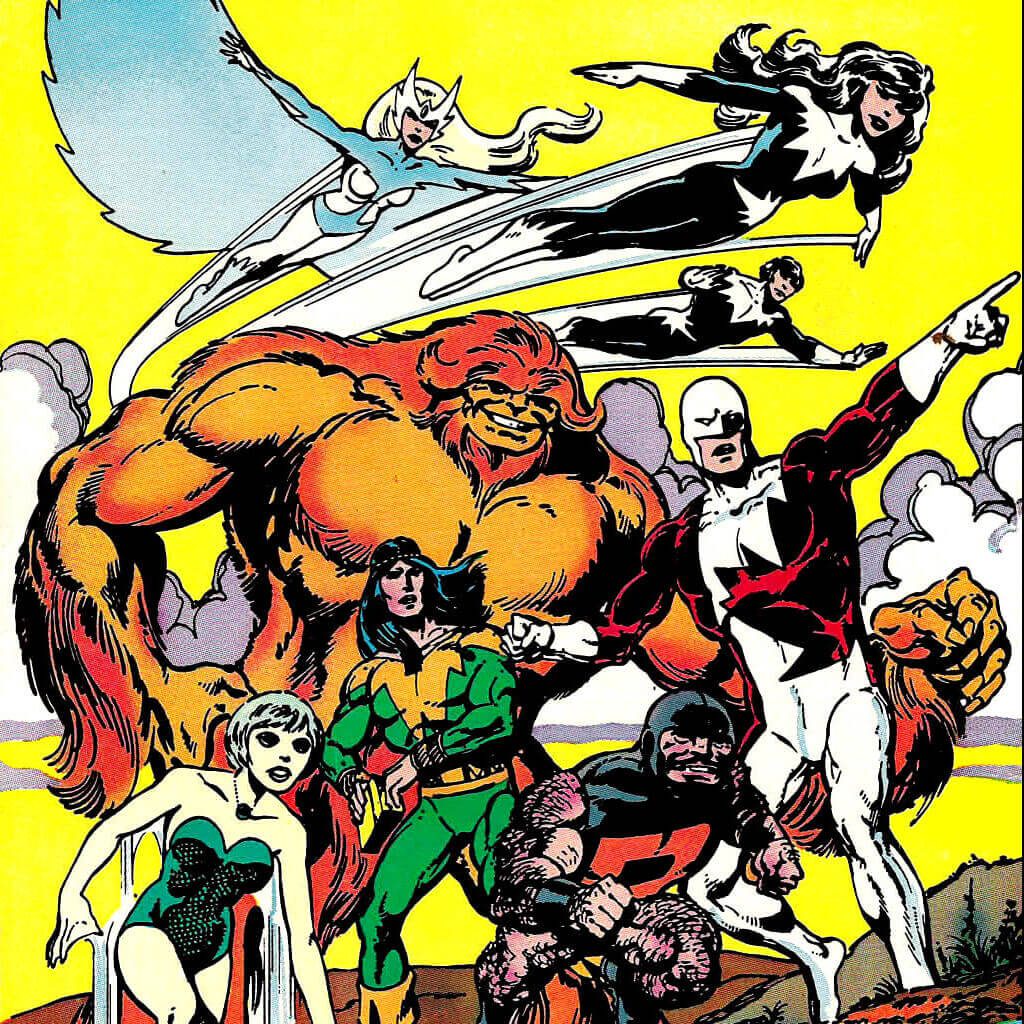

Of course, I eventually picked up those ROM comic books, which are still a favourite of mine. Over a 75-issue run well into the ‘80s, ROM’s surprisingly good comic lasted a lot longer than the toy ever did, thanks to the energetic corny delights of Bill Mantlo’s writing and Sal Buscema’s reliably expressive artwork.

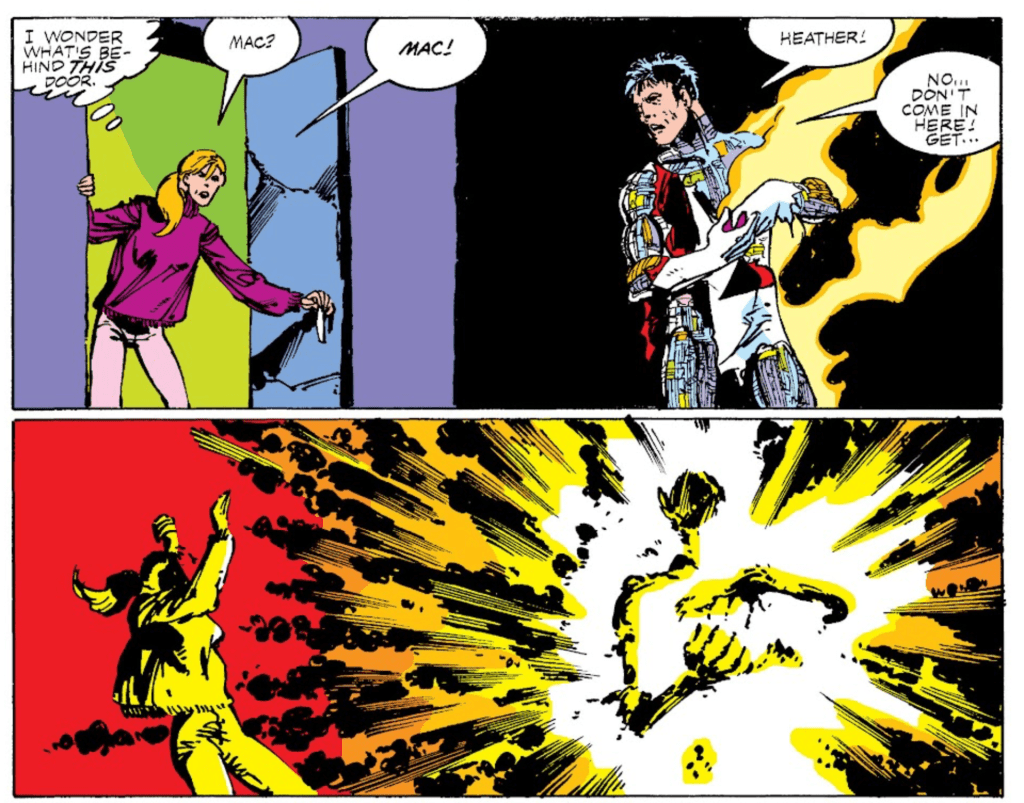

Over several years Mantlo spun a story of ROM, who sacrificed his humanity to battle the evil Dire Wraiths. It was never revolutionary comics but it was always good fun, and unlike so many comic book series it actually had an ending, which I really appreciated.

I loved those ROM comics, but I was never able to find myself a vintage ROM Parker Brothers toy. They kind of flopped and you never saw them at yard sales or swap meets and there wasn’t an internet to search then. These days, you could drop a few hundred bucks for one on eBay, but I’m not that dedicated to reliving my childhood fantasies of having all the cool toys.

But then the other day, I saw a new Marvel Legends ROM action figure for a decent price online – sure, it wasn’t the 13-inch tall “electronic action toy” of yore but it was pretty darned shiny with all ROM’s fancy accessories and that glam silver iconic spaceknight sure did look appealing. (And to be totally honest, it’s a much better looking action figure than the somewhat awkward 1979 toy.)

So I bought my ROM.

And gosh darn it, he is still pretty cool, I think.

Maybe next I can find a cheaper modern version of those super cool 24-inch tall Shogun Warriors toys that the kid down the road had. After all, a spaceknight’s work is never done.