One of the secrets of Bob Dylan’s success is his enduring mystery. Dylan has forged a 60-year career out of being opaque, inscrutable…. a “complete unknown,” if you will.

I’ll admit, I’m kind of a sucker for rock star musical biopics, even when they’re terrible. I watched Elvis and Walk The Line and Bohemian Rhapsody and I embrace the cheesy “rags to riches to overdose” narrative of such films, even when my head admits they’re not always great movies.

A Complete Unknown is a deep dive into Bob Dylan’s early years that does its share of romanticising and mythologising… but then again, hasn’t Dylan himself been doing that since he was a kid? For me, it hit the spot by embracing the many mysteries of Bob, revelling in music biopic cliches while being just prickly enough to feel real.

Timothée Chalamet is really far too pretty to be young Bob, who had a reedy, squinty babyface, but he nicely summons up the keen intelligence, peculiar charisma and somewhat mercenary ethics of young Bobby. Dylan rode into New York from rural Minnesota pretending to be everything from a hobo to a carnival worker. He threw aside his birth name of Zimmerman and became a kind of perpetual musical sponge, absorbing everything and synthesising it into something kind of new.

A Complete Unknown is about the birth of an artist who’s also a magpie, a wry cynic and also kind of a genius who’s not really a very nice guy. Dylan is called an “asshole” a couple of times in the film, which thankfully doesn’t try to show him as some kind of saintly hero. We avoid some big teary monologue where Bob Dylan reveals all the dark secrets that motivate him.

This exchange is as close as A Complete Unknown gets to peeking behind the mask: “Everyone asks where these songs come from, Sylvie. But then you watch their faces, and they’re not asking where the songs come from. They’re asking why the songs didn’t come to them.“

Chalamet’s natural teen idol charm is cleverly subverted just enough to make his Dylan feel like an echo of the thin wild mercury sound of the man himself. (And while he doesn’t sound exactly like Dylan singing, he sounds close enough to make it work, and lipsynching Dylan would’ve been even weirder.)

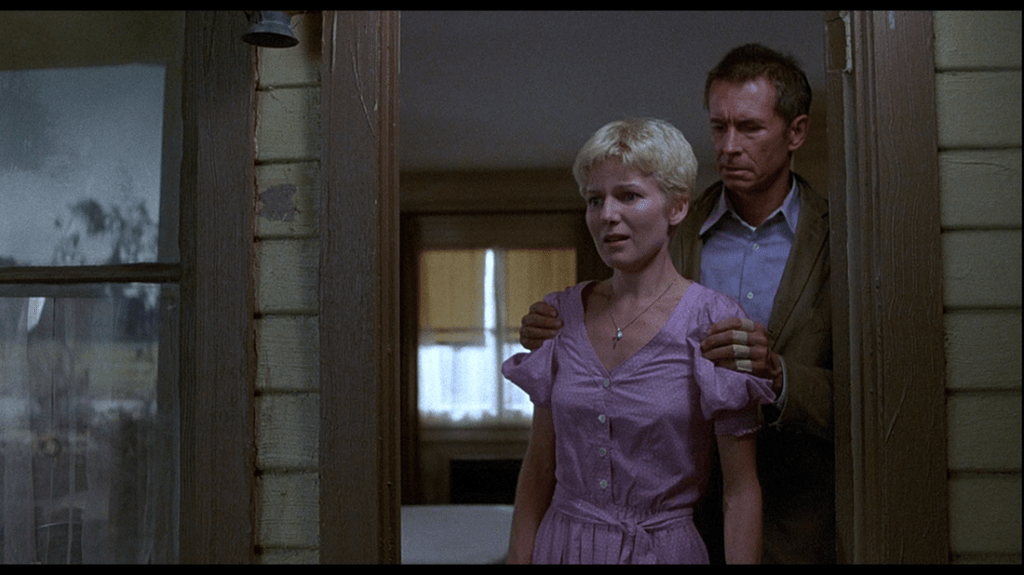

A Complete Unknown takes the great Bob Dylan creation myth and hits all the beats – his turn from folk music to electric, his wry confidence, his thorny romance with Joan Baez, his worship of Woody Guthrie. The movie follows Dylan from his arrival in New York as an eager kid up through his explosion into stardom in the mid ‘60s, and its big emotional turn is in Dylan’s moving from stark and preachy folk into raw and raucous rock, culminating in his famously defiant “electric” performance at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival.

A Complete Unknown wrings Dylan’s transformation for a lot of drama that might seem a bit hokey from 2025 eyes – so he’s playing an electric guitar now, so what? – but it’s worth remembering that Dylan’s “betrayal” of folk was a big deal back in the day. (Ed Norton‘s marvellous supporting turn as folkie Pete Seeger really captures the man’s uniquely kind heart and endearing dorkiness.)

As anyone who’s dipped their toes into the vast waters of Dylanology knows, there’s an infinite number of Bobs in the Dylanverse. (At least 80, as I painstakingly rambled on about a few years ago!) There’s no way A Complete Unknown, which follows a fairly basic biopic blueprint, could satisfy everyone, and we’ve certainly got cinema bizarro like Todd Haynes’ I’m Not There or Bob-starring oddities like Masked And Anonymous to fill any taste.

Watching Martin Scorcese’s superb documentary No Direction Home again recently, which follows Dylan’s 1966 tour of Britain in some dazzlingly vibrant footage, I was struck by how angry many of the British fans interviewed at the time were with Dylan’s new style. “I think he’s prostituting himself,” one barks. Yet to my eyes now, the hyper electric Dylan of 1966 is quite possibly his finest era. God only knows what would’ve happened if social media existed at the time.

Unknown works for me because it never quite pretends to be definitive, and knows there’s many more alternate Bob stories to be told. But hey, it’s turning new audiences on to Dylan music, got a bunch of Oscar nods, and is a reminder that after nearly 84 years walking this Earth, there’s still nobody quite like him.

Is it 100% true? It’s pretty and darned entertaining, but perhaps its biggest success is in carefully keeping Bob Dylan’s true motivations a complete unknown.