What is it: The first “midnight movie,” the surrealist “acid western”, “the weirdest western ever made.” Director Alejandro Jodorowsky’s extreme cult hit El Topo was a groundbreaking, aggressive statement that helped to change cinema, taking western movie tropes and turning them into a bizarre, questing meditation on morality and enlightenment. Populated with grotesque images and moments of startling beauty, it’s soaked in blood, disorienting with its casting of real-life disabled or maimed performers, and the kind of movie all the film cognoscenti say that you really must see at least once. So, finally, I saw it once.

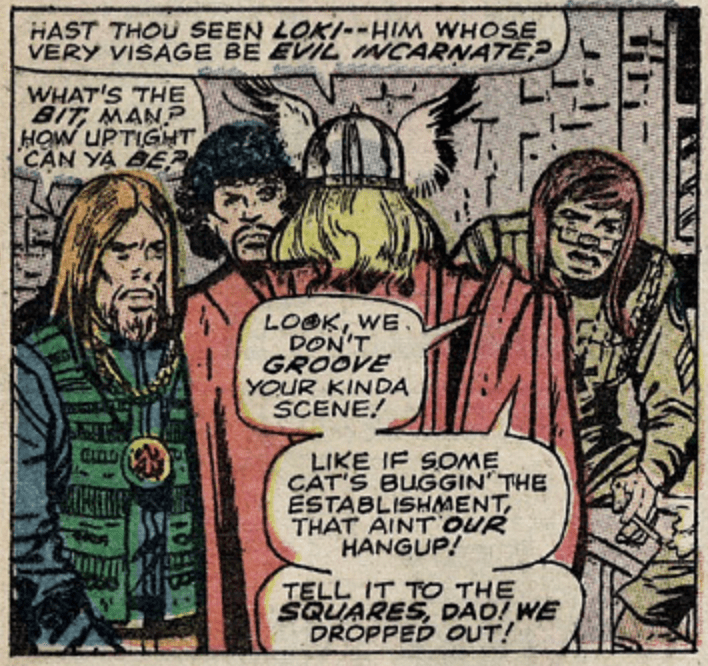

Why I never saw it: For a movie that’s legendarily strange, El Topo has had a difficult path to actually being easy to see. It got tangled up in legal wrangling and was only released on DVD in 2007. The first of Jodorowsky’s films I’ve dipped into, El Topo is often called Jodorowsky’s ‘most accessible’ movie. I’m a fan of weird, but weird is very much in the eye of the beholder, ain’t it? (I still recall a date who I took to the Michael Bay movie The Rock talking about how strange and weird it was afterwards. Reader, we did not date again.) I love my Lynch and Cronenberg but am fully aware I’m a mere babe in the wild, vast woods of weird cinema, and have to admit I wasn’t quite sure what to expect with El Topo.

Does it measure up to its rep? The big question for every viewer of El Topo is whether or not it’s just a procession of cruelty with no deeper meaning. When the subject is nothing but “people are terrible,” it gets old, fast. El Topo starts off feeling a bit like a particularly dark spin on the whole “lone gunman wreaks vengeance” plot, following the man in black and his inexplicably naked young son (Jodorowsky himself plays the gunman) as they discovered a gutted village filled with dead people, track down the corrupt bandits responsible and execute them. The gunman then abandons his son for a rescued hostage and ends up on a surreal quest through the desert to kill four gunmen legends and become “the best there is,” a quest that gets increasingly stranger. In the end, the gunman disappears and is reborn years later in a cave, bleached white and now a mystical holy man who can’t quite escape his violent past.

While it’s hefty with the DNA of John Wayne, Clint Eastwood, Django and other western icons, to me it also shares an awful lot with books like the dark, biblically violent Cormac McCarthy novel Blood Meridian, which also sees the west as a seething quagmire of man’s worst instincts, or of Robert Bolaño’s epic 2666, which turns an unflinching catalogue of murders into something stranger and deeper. If anything, I have to admit that El Topo wasn’t quite as weird as I imagined it might be, especially in its more grounded first half. Where it sticks, however, is the insinuating ugly beauty of its vision, where Jodorowsky stages violence with an icy calm eye as men, women and even children are gunned down, and in the end, we’re not certain if he’s saying life is worth nothing – or worth everything. There’s precious little hope in its final moments, suggesting an endless circle of violence and thwarted redemption.

Worth seeing? On one level, El Topo probably doesn’t seem quite as groundbreaking as it might have 52 years ago. We’ve had plenty of deconstructionist westerns: Clint himself in Unforgiven, Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man and much more, and plenty of weird, brutal cinema. Yet despite its more grotesque flourishes, El Topo is still a singular, fierce vision. His use of real-life amputees and dwarves is confronting, as is the brief animal deaths and sexual violence. Jodorowsky claimed back in the ‘70s that he really raped his actress co-star in one vivid, violent sequence, although he’s since walked that back as a big-mouthed publicity stunt. Either way, El Topo is still a triggering film, but it has value as some kind of warped mirror on society. Seen 50 years on, yes, El Topo does seem madly self-indulgent, frequently sadistic and exploitative. Yet it’s also hard to stop thinking about some of its imagery. I’m a sucker for the vision of a man in black, riding across the desert, on his way to who knows where, but knowing there’ll always be blood in the end.