I’ve been a Shakespeare fan ever since high school, and even volunteered regularly for several seasons at Auckland’s wonderful Pop-Up Globe revival. I’ve seen quite a lot of Shakespeare on stage over the years… or, until recently, so I thought.

When I start to actually think about it, I’ve realised I’ve only seen about half of Shakespeare’s 37 (more or less) plays actually performed live on a stage, which makes me feel like a lot less of a Shakespeare fanboy than I thought I was. (There’s even a name for doing it – “completing the canon.”)

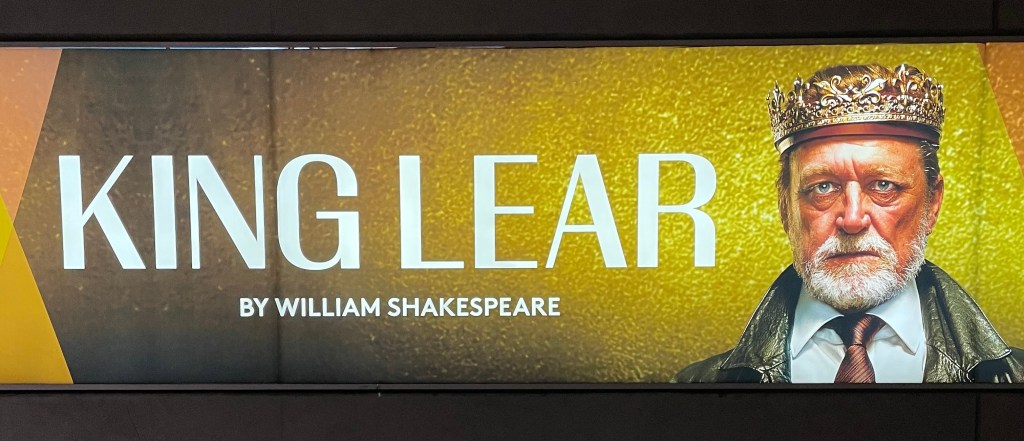

I finally filled one of my most notable gaps this week by seeing Auckland Theatre Company’s fierce, excellent production of King Lear starring and directed by Michael Hurst, a brutal escalating powerhouse of a tragedy which – although I’ve seen several filmed productions – I’d somehow never managed to see performed live in all my mumblety-mumble years. (Lear is still on for a few more weeks and it is most highly recommended if you’re in Auckland!)

Lear was by far the best-known Shakespeare play I had missed out on, and added to the tally earlier this year was another one I’ve inexplicably missed seeing performed live, a highly enjoyable outdoor lakeside theatre version of Antony and Cleopatra at Auckland’s Shakespeare in the Park.

Some people idolise pro wrestlers, or rugby stars, or pop singers. But honestly, for me, among my top cultural heroes, the ones whose achievements I both appreciate and yet cannot quite imagine doing myself, are the stage actors.

Imagine getting up and speaking hundreds of Shakespeare’s verses and monologues before a crowd, and imagine doing that nearly every night, while wearing a bulky costume, possibly having a stage fight or three, and also managing to put some life into your role. It’s a herculean accomplishment that I sometimes think we don’t quite appreciate as much in the age of ever-streaming content.

Michael Hurst, one of New Zealand’s great actors, wrung himself out over the course of nearly three hours in King Lear the other night, delivering a tense, nervy and unhinged performance of what’s often been called the greatest role an actor can hope to perform. I was sweaty and overwrought myself just watching him and couldn’t imagine what it’s like to be asked to deliver that kind of all-in acting, again and again.

It’s easy to love Shakespeare without seeing it performed, of course, and there have been a lot of magnificent movie and television versions of the plays. But the stage is the crowning way to appreciate Shakespeare, and the beauty of it all is, you’ll never quite see the same play twice.

Several plays I’ve seen quite a few times live, like Richard III at Oregon’s famed Ashland Shakespeare Festival and at the late great Pop-Up Globe. I saw Hamlet, Henry V and Othello so many times at the Globe that I grew to appreciate the tiny, almost indistinguishable differences in line readings each time, the slight changes in gesture that altered an entire scene.

But there’s an awful lot that still, decades into being a Bard-idolator, I’ve never managed to see performed live. The list has shrunk, but it’s still a lot longer than I imagined – and I hope to gradually seek out the missing plays in coming years.

It’ll be tricky, because a lot of the ones that are left are ones you rarely ever see performed. Everyone has seen some version of Romeo and Juliet, I’d wager. How many of us have watched Troilus and Cressida on a stage?

A particular blind spot is an awful lot of the histories, all those Henry VI Part 2 and 3s and such, and a heap of the more rarely-performed plays like Pericles, Cymbeline and Timon of Athens. (Has anyone even seen Timon of Athens? Come on!)

Many of the rarer works I have seen superbly translated to film, like Ralph Fiennes’ astoundingly intense translation of Coriolanus to the war-torn Balkans or Julie Taymor’s vivid and grotesque slasher-horror of Titus Andronicus with Sir Anthony Hopkins. (It’s hard to imagine most local theatre companies putting on Titus, what with the cannibalism and mutilation and murder and all.)

One’s goals become a little less ambitious as you get older. Trying to tick off all 37 or so of Shakespeare’s plays on stage is a small one in the big picture, but heck, I’ll give it a go. I don’t know if I’ll ever “complete the canon,” given how little New Zealand is and how rarely some of the plays are put on. At the very least, I’ll see some wonderful plays, and that’s the experience to remember.

To quote one of those ones I haven’t seen yet, here’s a line from Troilus and Cressida that seems apt:

“Things won are done, joy’s soul lies in the doing.”

Therefore, since brevity is the soul of wit, And tediousness the limbs and outward flourishes, I will be brief. — Polonious

Therefore, since brevity is the soul of wit, And tediousness the limbs and outward flourishes, I will be brief. — Polonious As I’ve said before, I find Shakespeare bottomless – an infinity of meanings can be found in his works, and new twists reveal themselves in every new look. Hamlet is perhaps his crowning jewel as an artist, a play about a young man who asks the question every single one of us asks at some point in our lives: To be? Or not to be?

As I’ve said before, I find Shakespeare bottomless – an infinity of meanings can be found in his works, and new twists reveal themselves in every new look. Hamlet is perhaps his crowning jewel as an artist, a play about a young man who asks the question every single one of us asks at some point in our lives: To be? Or not to be? What does it all mean? After hours and hours of Hamlet this season, I’m still not quite sure.

What does it all mean? After hours and hours of Hamlet this season, I’m still not quite sure. One of my highlights of the last three summers has been working at the remarkable

One of my highlights of the last three summers has been working at the remarkable  I’ve loved Shakespeare since a superb high school teacher (thanks, Mr. Lehman) showed us how the Bard wasn’t all dusty words and impenetrable verse, but a living, breathing body of work that contains some of the greatest stories ever told. Shakespeare is meant to be seen, not merely read aloud in a halting adolescent voice in a dry classroom.

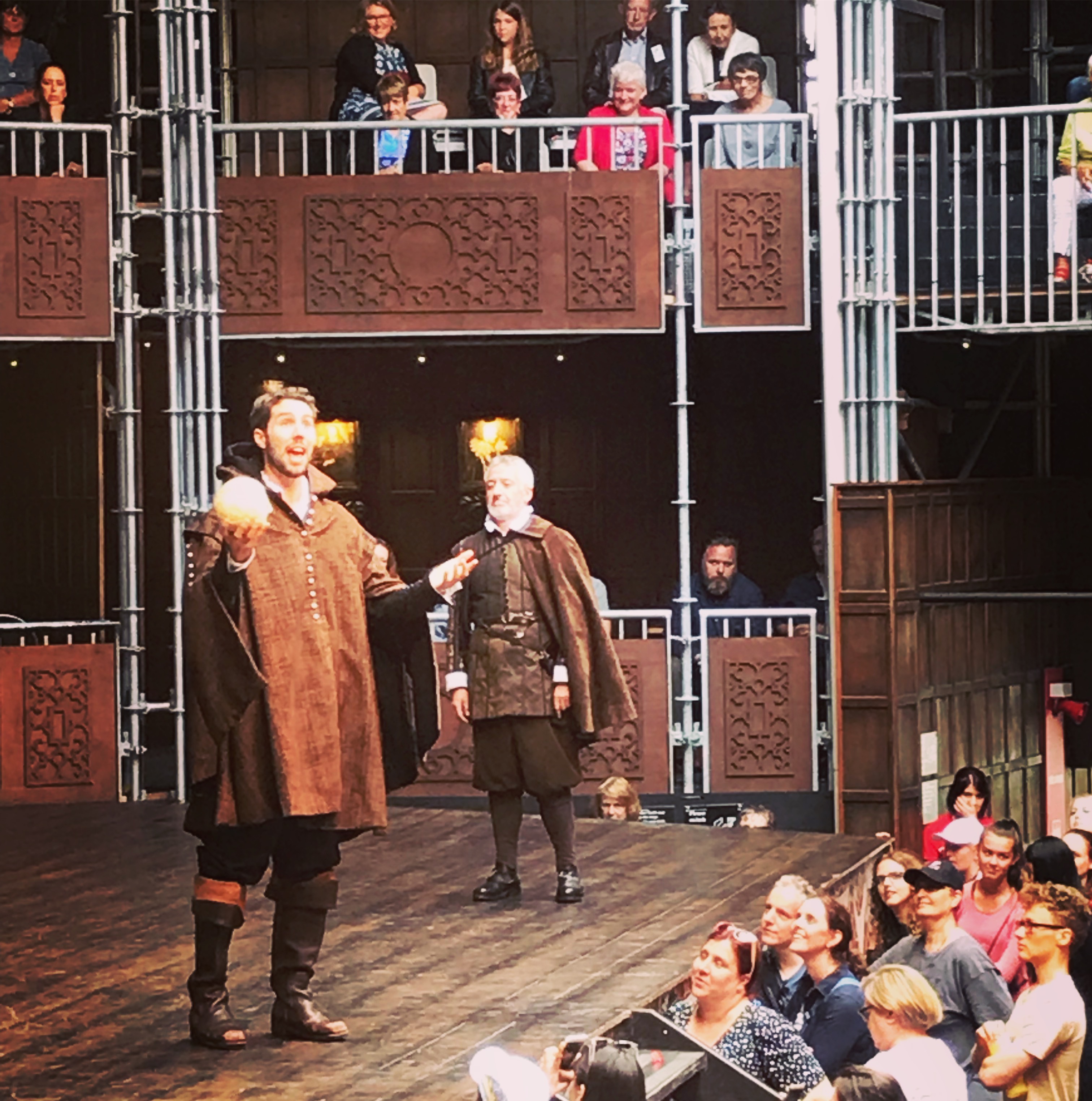

I’ve loved Shakespeare since a superb high school teacher (thanks, Mr. Lehman) showed us how the Bard wasn’t all dusty words and impenetrable verse, but a living, breathing body of work that contains some of the greatest stories ever told. Shakespeare is meant to be seen, not merely read aloud in a halting adolescent voice in a dry classroom. A joy for me is seeing how into the plays the audience still are in 2019. This isn’t boring Shakespeare – trust me, when the stage blood starts gushing into the audience during the bloody close of Richard III, you wouldn’t call this stuffy. There’s a witty, relaxed vibe that’s perfect for a New Zealand summer. We get all kinds of crowds – young, old, repeat customers and those who’ve never seen a Shakespeare play in their life.

A joy for me is seeing how into the plays the audience still are in 2019. This isn’t boring Shakespeare – trust me, when the stage blood starts gushing into the audience during the bloody close of Richard III, you wouldn’t call this stuffy. There’s a witty, relaxed vibe that’s perfect for a New Zealand summer. We get all kinds of crowds – young, old, repeat customers and those who’ve never seen a Shakespeare play in their life.