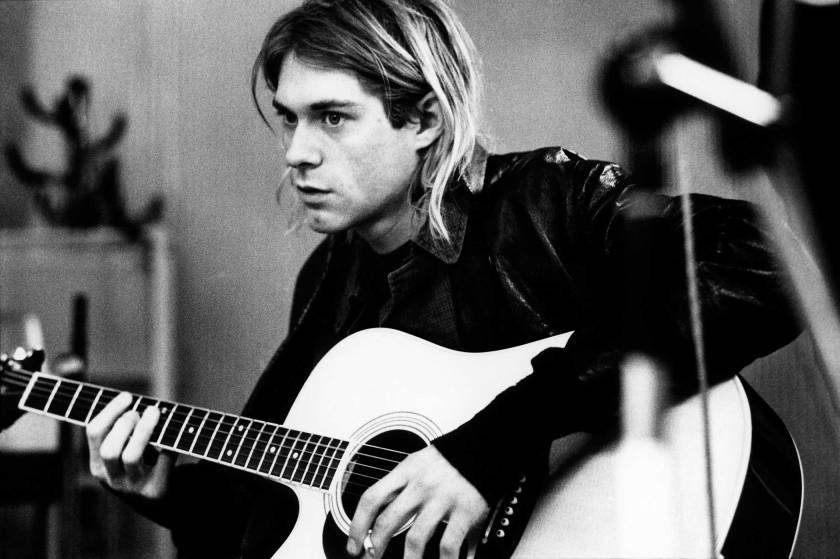

January 2019: …Let’s wrap up That’s So ’90s Week here on the blog with a multiple-flashback-approach. Here’s a newspaper column I wrote in April 1999, on the fifth anniversary of Kurt Cobain’s suicide, trying to make sense of that moment in time. Revisiting my words now in 2019, nearly 25 years on (!) after Kurt’s death, it’s a weird echoing effect indeed. A reminder that something sad never quite leaves your brain, that few moments are ever completely one thing. It’s one of my favorite of the couple hundred columns I wrote, back when there were newspaper columns.

April 1999: Five years ago now.

Few people noticed it and few comments were made in the news about it, but Friday was the fifth anniversary of the day Kurt Cobain died. The lead singer of the grunge rock band Nirvana took his own life with a shotgun in an apartment in Seattle five years ago.

In his suicide note, Cobain quoted Neil Young’s lyric about how it’s better to burn out quickly than fade away.

The thing no one told Kurt is that everyone fades, in fact and in memory.

A lot of you out there could probably give two tosses for Kurt Cobain’s sorry fate. Just another screwed-up junkie musician.

But I cared about him then and I care about him now, in the strange way you can care for someone you’ve never met who touched your life with their work – the way I care about, say, John Updike or George Lucas or Michael Stipe. It’s an abstract emotion but that makes it no less real.

A song can capture a moment forever. I hear “Pretty In Pink” by O.M.D. and I’m 15 again, instantly. The Velvet Underground always conjures up drunken all-night college parties, me leaning with my head up against the speaker.

And Nirvana. Nirvana was the music I listened to when I drove, loud clashing and screaming about the world. The music spoke of the underbelly of life, the flesh-rendering pain love can cause, the numbness a life can slip into, potential wasted. It was the music for me, then, the person I was then.

Strangely, the day Kurt Cobain died was one of the finest days I had ever known.

That morning, I had found out that I was the recipient of a summer internship with Billboard magazine in New York City.

I’d won out over dozens of other journalism students from around the country, and I’d spend the summer working for one of the biggest music magazines in the world, in the heart of the Big Apple. It was all too good to be true, and the world itself seemed to blossom and spread around me, acres of possibility and potential flowering.

I decided to drive home, from college in Mississippi up to Memphis to tell my parents the good news. I turned on the radio, and they were playing Nirvana, “Come As You Are,” and I began humming along. The song ended, and I heard the DJ say something about “the late Kurt Cobain.” My heart skipped the tiniest bit, the way it always does when you first hear bad news.

I gleaned the rest of the details over the next few minutes. Found in Seattle. Suicide. A shotgun. Heroin problems.

Kurt Cobain was dead.

It was a black spot, a small black spot on an otherwise pristine day.

I drove around Memphis that sunny April afternoon for a good while, playing the tape of Nirvana’s In Utero album I’d kept in the car and thinking what I considered mighty deep philosophical thoughts about life, the universe and everything, about how maybe only a razor’s edge of choice and circumstance separates the cocky college kid from the rock star with a shotgun in his mouth.

The sun splintered jewels of light into the car as I drove, pinballing between highs and lows.

I felt insanely happy one second – I was bound for New York City, where all things begin, where I could be anything! – and terribly apprehensive the next – New York alone, I was only 22, what would happen to me there?

The black spot on the day sat there, too, imprinting on the back of my brain a vague terror of demons unseen, unknowable.

“What else should I be? All apologies… What else could I say… everyone is gay… What else could I write… I don’t have the right… What else should I be? All apologies…”

—Kurt Cobain, 1967-1994

Yeah, he was a junkie. He was a self-proclaimed screwed-up loser who felt he didn’t deserve half of the adulation and acclaim given him during his short, sad life.

Kurt Cobain was not the nicest guy, and his music reflected that – the burnt-throat garglings of someone who would wake up some mornings with absolutely no idea of why he was here or what the point of it all was.

His screams and fractured musical chords tried to make some sense of that chaos. I would not wish his life on me or anyone, but what he said to me with his music made a difference to me, then, and when I listen to it now it still resonates.

I wrote a column, back then in spring 1994, about Kurt Cobain’s death.

I wrote: “I know there were others out there who gladly drank in Nirvana’s music, their corrosive rage and pain, and who saw Cobain as another scared, angry kid like themselves. Cobain’s music didn’t appeal to everyone: it was probably just scary noise to a lot of you reading this. But to me, there was something that could seem so very eloquent about a scream. Nirvana’s music could be beautiful in its ugliness.”

Kurt Cobain’s music came from pain. But in some way, the raw abrasiveness of it all was a healing salve to me. Ugly and beautiful, now strange and gone with no more to come from that dark and gifted place in Kurt Cobain’s heart.

It was a beautiful day there, driving around Memphis five years ago. That little black spot that was Kurt Cobain’s end… perhaps it made the air and sunlight seem sweeter still.

Another fine singer who is a favourite of mine put it best, perhaps, in a song of his own:

“There’s a bit of magic in everything, And some loss to even things out.”

–Lou Reed, “Magic & Loss”

For That’s So ‘90s Week, I’m taking a look back at some of the pop culture epherma of the ’90s that sticks with this ageing Gen-Xer.

For That’s So ‘90s Week, I’m taking a look back at some of the pop culture epherma of the ’90s that sticks with this ageing Gen-Xer. It’s like a petri dish of what social scientists might imagine the prototypical ‘90s Gen-X life story to be. Pete dishes on an oil rig, in Alaska, in chain restaurants and communes and tiny roach-infested dives. As his zine grows, he becomes a folk hero, and even appears on David Letterman (sort of – I won’t spoil the story, which is totally on brand for Pete). These days he’d probably be some kind of live-streaming influencer, but in the ‘90s a guy like Pete would just drift into your life occasionally, a battered zine showing up in the mail or a phone call from a guy wanting to crash on your couch for a week.

It’s like a petri dish of what social scientists might imagine the prototypical ‘90s Gen-X life story to be. Pete dishes on an oil rig, in Alaska, in chain restaurants and communes and tiny roach-infested dives. As his zine grows, he becomes a folk hero, and even appears on David Letterman (sort of – I won’t spoil the story, which is totally on brand for Pete). These days he’d probably be some kind of live-streaming influencer, but in the ‘90s a guy like Pete would just drift into your life occasionally, a battered zine showing up in the mail or a phone call from a guy wanting to crash on your couch for a week.

But “Frasier.” Ah, “Frasier.” For me, “Frasier” is the warm witty blanket of ‘90s TV, perfectly constructed one-act farces that I can watch over and over again without tiring. If asked, I’d have to say that I think “Frasier” is the peak of the traditional sit-com form – one that’s been deconstructed and reconstructed often since, but rarely bettered.

But “Frasier.” Ah, “Frasier.” For me, “Frasier” is the warm witty blanket of ‘90s TV, perfectly constructed one-act farces that I can watch over and over again without tiring. If asked, I’d have to say that I think “Frasier” is the peak of the traditional sit-com form – one that’s been deconstructed and reconstructed often since, but rarely bettered.

All right, it’s time to post again and stop hanging out at the beach and such. It’s 2019, oh man oh man, and that means 1999 was 20 years ago, which means the ‘90s ended 20 years ago, which means my 20s ended 20 years ago and I am officially old.

All right, it’s time to post again and stop hanging out at the beach and such. It’s 2019, oh man oh man, and that means 1999 was 20 years ago, which means the ‘90s ended 20 years ago, which means my 20s ended 20 years ago and I am officially old. I’ve been collecting comics for (gulp) nearly 40 years now, but the 1990s was the closest I ever came to abandoning my monthly fix. Marvel and DC’s mainstream comics hit their gaudy nadir, and I was dead broke a lot of the time anyway. But there was an awful lot of brilliance to be found in the spirit of independent comics – Hate, Eightball, Cerebus, Yummy Fur, Naughty Bits, Dirty Plotte, DC/Vertigo’s Sandman – and that kept me going.

I’ve been collecting comics for (gulp) nearly 40 years now, but the 1990s was the closest I ever came to abandoning my monthly fix. Marvel and DC’s mainstream comics hit their gaudy nadir, and I was dead broke a lot of the time anyway. But there was an awful lot of brilliance to be found in the spirit of independent comics – Hate, Eightball, Cerebus, Yummy Fur, Naughty Bits, Dirty Plotte, DC/Vertigo’s Sandman – and that kept me going. Throughout ACBC, we see the twin poles of creative independence and corporate greed battle, greed usually winning. Marvel sells 8 million comics and goes bankrupt a few years later. DC kills Superman, breaks Batman’s back, makes Green Lantern a mass murderer, chops off Aquaman’s hand (spoiler: they all get better). Image Comics is formed in 1992, and despite beginning with some pretty awful clenched-teeth superheroic angst, it’s still here in 2019 and publishing a diverse and intelligent line of books. Former Marvel editor-in-chief Jim Shooter, on the other hand, keeps popping up throughout the book starting up new companies that quickly fade away.

Throughout ACBC, we see the twin poles of creative independence and corporate greed battle, greed usually winning. Marvel sells 8 million comics and goes bankrupt a few years later. DC kills Superman, breaks Batman’s back, makes Green Lantern a mass murderer, chops off Aquaman’s hand (spoiler: they all get better). Image Comics is formed in 1992, and despite beginning with some pretty awful clenched-teeth superheroic angst, it’s still here in 2019 and publishing a diverse and intelligent line of books. Former Marvel editor-in-chief Jim Shooter, on the other hand, keeps popping up throughout the book starting up new companies that quickly fade away. I’ve always considered myself a pretty adequate comics history nerd, but there were entire publishing companies unearthed in this book I’d never heard of. Sacks and Dallas keep the constant flow of information moving in an entertaining way, and there’s tons of juicy comics-biz gossip peppered throughout.

I’ve always considered myself a pretty adequate comics history nerd, but there were entire publishing companies unearthed in this book I’d never heard of. Sacks and Dallas keep the constant flow of information moving in an entertaining way, and there’s tons of juicy comics-biz gossip peppered throughout. I’m in my 12th year as a New Zealander now, a statistic which kind of stuns me. That’s about a quarter of my life now, and I’ve been a dual citizen of two nations for several years. And I’m finally starting to think of January as summer.

I’m in my 12th year as a New Zealander now, a statistic which kind of stuns me. That’s about a quarter of my life now, and I’ve been a dual citizen of two nations for several years. And I’m finally starting to think of January as summer. I’ve finally noticed these last few years that my mind has shifting toward accepting January as the summertime, toward seeing Christmas as summer holidays. The heat and sun seems normal. In a way, it makes a lot more sense to roll everything together – the bustle of Christmas, the optimism of a

I’ve finally noticed these last few years that my mind has shifting toward accepting January as the summertime, toward seeing Christmas as summer holidays. The heat and sun seems normal. In a way, it makes a lot more sense to roll everything together – the bustle of Christmas, the optimism of a