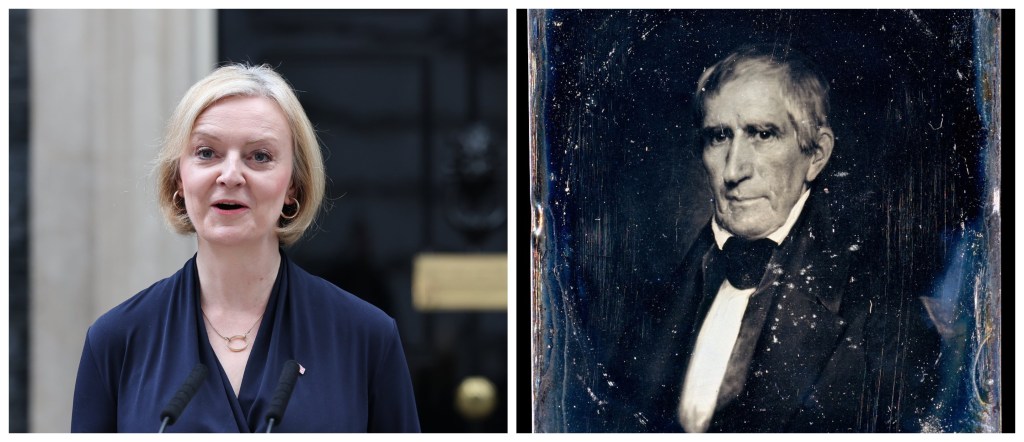

Watching British Prime Minister Liz Truss’s brief tenure go down in flames has been an exciting spectator sport. After a mere 45 days in office, she’s resigned, and while the debates over her car-crash of a tenure will be going on for some time, eventually, she’ll be a footnote – the shortest serving UK Prime Minister ever. At least she’ll have company, in that weird world of history’s short-timers.

In fact, Truss is not anywhere near the record set in other countries for the shortest leadership – the briefest US President lasted a mere 31 days, while in New Zealand, our shortest-serving Prime Minister was only 13 days. In Australia, it was just eight!

US President William Henry Harrison is a footnote in Trivial Pursuit games. He died a mere month after his inauguration, the then-oldest US president at the age of 68, after giving a nearly two-hour inauguration speech in the freezing cold. His health declined over his short term, not helped by a habit of going for long walks without a coat or hat in wintry March weather. Because it was 1841, his treatment during his illness consisted of fun things like enemas, “cupping,” castor oil, opium, and a lovely cocktail of camphor, wine and brandy. It didn’t help. He lingered until April 4, 1841, only his 31st day in office. He gets points for what is perhaps the most “I love my job” deathbed speech of all time – “Sir, I wish you to understand the true principles of government; I wish them carried out, I ask nothing more.”

Harrison’s death has long been attributed to pneumonia, but more recent research has found it might have been some kind of enteric fever, spawned by Washington’s then literal swamps. He didn’t leave a whole lot of accomplishments other than running what might be considered the first “modern” campaign, yet his death, the first of a US President in office, did help establish the precedent of the Vice-President becoming President. Many thought John Tyler should only become an “acting President” but he simply assumed the full office, which is how it’s worked ever since.

Here in New Zealand our shortest serving leaders have mostly been during the earlier days of British colonial government. Henry Sewell was New Zealand’s first premier, Prime Minister or “colonial secretary” from May 7 to 20, 1856, during the very earliest days of our colonial government – “he was too reserved and elitist for the rough and tumble of colonial politics, as the brevity of his premiership showed.” Other earlier PMs had pretty short terms as well. In modern times, the late Mike Moore served for only 59 days in 1990 before his Labour Party was voted out of office. Despite his short term, he went on to have a pretty solid career in world politics and was given that crowning kiwi accolade when he died at age 71 – “an everyday bloke.”

Across the ditch, there’s certainly been a lot of turnover in Australia’s Prime Ministers, including what I believe is the only Prime Minister ever lost at sea, but they’ve got work to do to catch up with poor Frank Forde, who only lasted 8 days in 1945. He became Prime Minister when John Curtin died suddenly, but a week later his Labor Party picked someone else to lead, and well, it was farewell, Forde.

Few will mourn Liz Truss’s brief term as Prime Minister, but its mere brevity indicates she’ll go down in history for one thing, at least – just maybe not the way she wanted.