The thing about Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is it’s not the story you think it is.

Mary Shelley was only a teenager when she wrote the book that has led some to call her “the inventor of science fiction.” At the very least, she certainly helped create some foundations for it. However, if you’ve binged on old Boris Karloff movies and are expecting Frankenstein the novel to be the same animal, you’re likely to be a bit befuddled.

The book has a rather average 3.8-star rating on GoodReads, with critics saying it’s “like watching paint dry” and “tedious.” Published in 1818, it does get off to a somewhat slow start, with a series of nesting first-person narratives from an Arctic ship captain, then Victor Frankenstein, and then finally the monster itself. There’s not a lot of what we jaded 2022 folk would call “action” and a lot of flowery romantic language.

But once you abandon expectations of a silent Karloff-ian zombie lurking in the shadows and Colin Clive shrieking “It’s alive!”, Frankenstein is still a pretty remarkable book which I return to every few years. It turned 200 years old just a few years back, so keep in mind its voice is almost closer to the era of Shakespeare than it is 2022. It is a novel of ideas and debate, rather than straight horror, although god knows plenty of horrible things happen to Victor Frankenstein and his creation.

The first time I “read” Frankenstein was in one of those adapted great works of literature children’s books, which stripped the story down to the essentials and ran some evocative illustrations to go with it. These days, my go-to version of Frankenstein is one with utterly gorgeous macabre drawings by the late, great Bernie Wrightson to go with Shelley’s text. More than some classic novels, I’ve always felt like Frankenstein cries out for a little art to complement the wordy text.

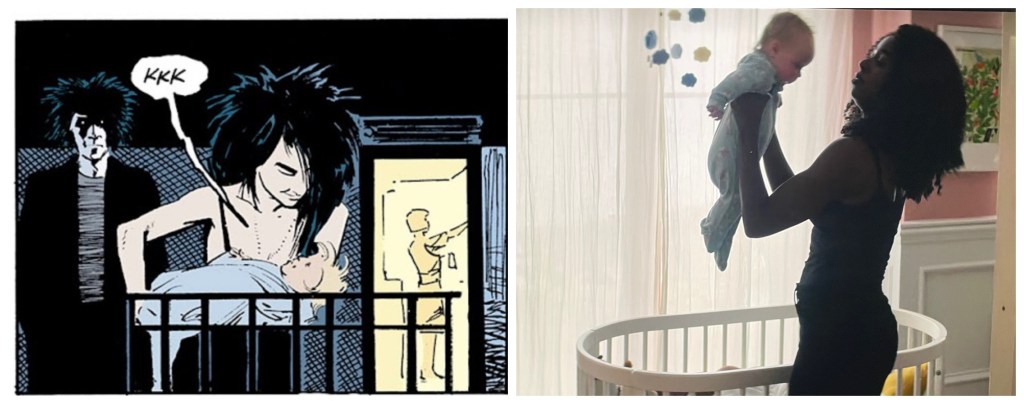

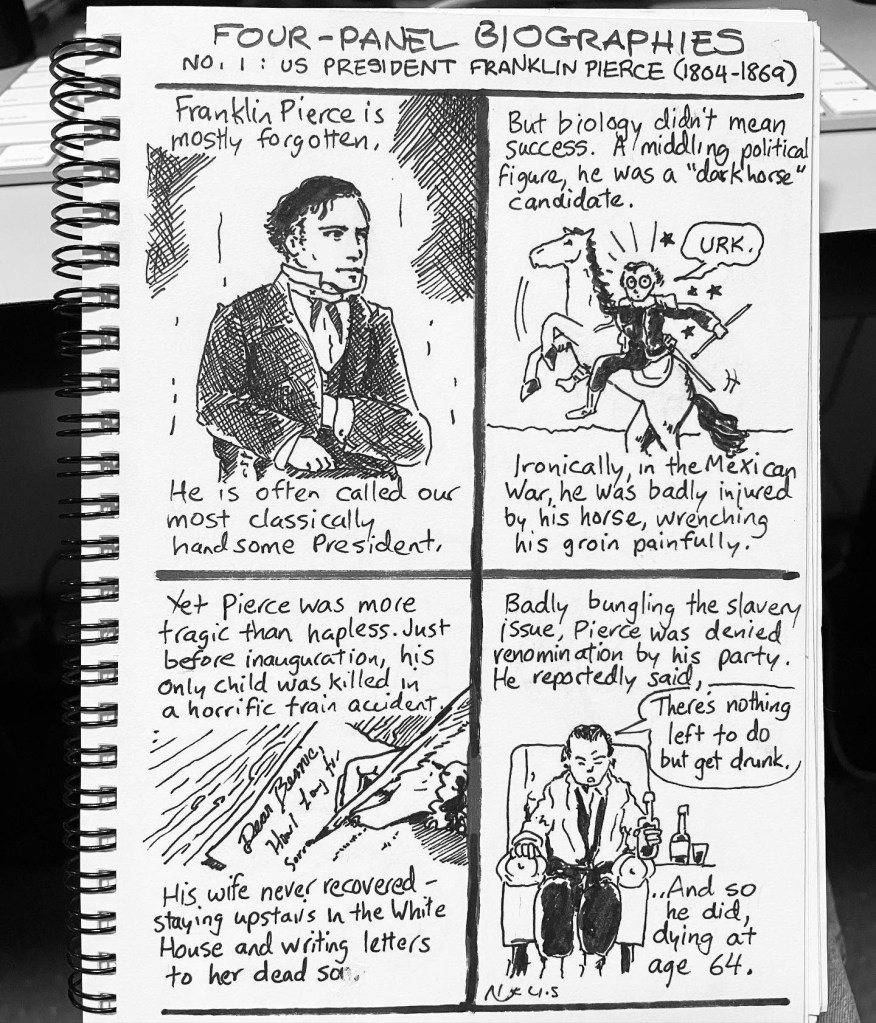

Like Bram Stoker’s Dracula, it’s another classic horror book that is quite different in tone than its many adaptations. So much of our image of what “Frankenstein” is comes from James Whale’s 1931 film – which I utterly adore, don’t get me wrong. Even the idea that the monster itself is somehow actually called “Frankenstein” emerged from those old Universal films. (In the books, he refers to himself as Adam at least once.)

The bones of Shelley’s story still stick with me years later. When I first read it, I was obsessed by the image of Frankenstein chasing his monster across the Arctic wastes that frames Shelley’s story, the idea of monster and creator pursuing each other into the frozen wastelands throughout eternity. I love Shelley’s questing monologues for the Creature, who is the polar opposite of Karloff’s silent, mournful monster. The Creature is violently angry at the world that scorned him but also gorgeously descriptive about his cursed place in it: “I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend.”

One of the most notable things about reading Frankenstein the novel is how all the scientific explanations for the monster’s creation we are so used to don’t appear at all. There’s no Igor, no labs filled with lightning, only a hint of grave-robbing. Shelley is almost coy about how the monster came to be, dismissing the technical details within a sentence or two. She is more interested in the question of duality – are monsters made, or are they created by the world’s reaction to them? The spark her book lit has fuelled a thousand other interpretations and expansions of her dark tragedy.

Hollywood has taken many, many swings at the Frankenstein story in the past century but never quite captures the book. Kenneth Branagh’s overwrought 1994 film has its moments of fidelity, but still piles on laboratories sparking and its campy excess misses the book’s haunted, spartan tone.

But I’m happy with that. There’s many great Frankenstein movies out there, but the novel that birthed all these monsters is very much its own animal, two centuries old now and still filled with wonder and horror and mystery about the world around us.