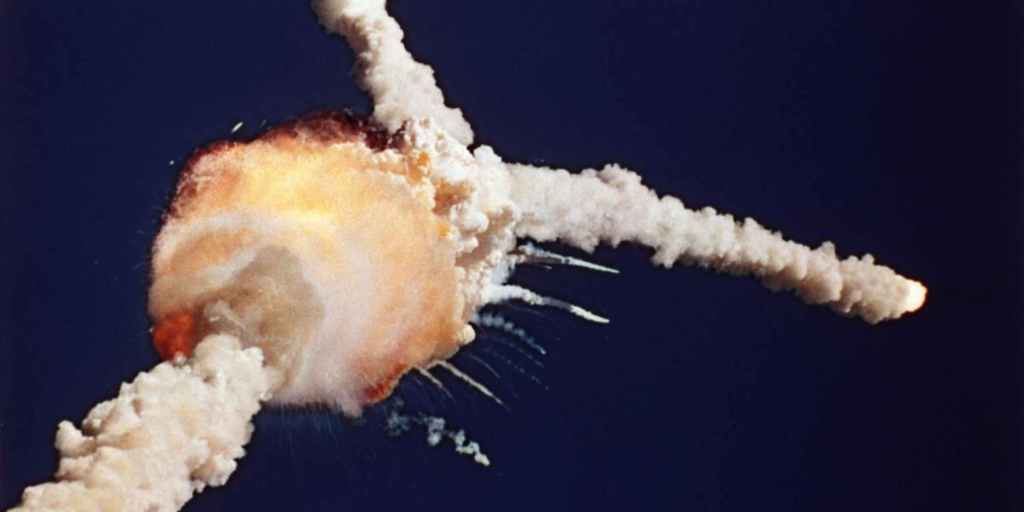

I remember the Challenger, coming apart in the infinite blue, 40 years ago today.

I was in eighth grade, on January 28, 1986, and our classroom came to a chattering halt that day when we heard that the space shuttle Challenger – with a civilian teacher on board, Christa McAuliffe – was gone.

“Gone” didn’t seem to make sense – while there had been NASA disasters long before I was born, this was something new and scary.

I fixated some on the fact that these astronauts were, and then suddenly weren’t, that they were vanished into the sky and the sea in that unforgettable image of the shuttle’s explosion and contrails melting into the sky. I don’t think our classroom was watching it on live TV, but I feel like someone in school was, because the news spread in a quick way that seems so foreign now when everyone carries the instant news in their pocket. The fact there was a teacher on board, a woman who could’ve been one of our teachers, and that her bold adventure ended so abruptly felt like a cruel joke.

For a good long while, all the students and teachers milled around, reacting. The normal school day stopped. I remember being pissed off that one of my friends took in the news with a laconic “well, they’re all dead” type remark. Didn’t he feel the existential horror of it all, or was I just a sensitive lad?

I’m not a huge fan of Ronald Reagan’s politics or the way a lot of his presidency laid the groundwork for 2026’s shitstorm, but I will give him this – his speech to the nation about the tragedy was one of the finest moments of presidential rhetoric I’ve ever seen, delivered impeccably. I still think of those lines: “We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and slipped the surly bonds of earth to touch the face of God.” Even for an avowed agnostic like me, there’s poetic comfort in those words.

Of course, consolation is foreign to the current occupier of that office, isn’t it?

I am often a bit saddened that lofty dreams of space seem to have taken a back seat in our current battered old world, although I have high hopes for the Artemis II mission.

It was probably the first big, truly big news event that I paid a lot of attention to. I kept the newspaper front pages for years, and perhaps I have them somewhere still, buried in a box. Previous to that I was vaguely aware of things in the wider world – I have vague memories of the death of Elvis being reported on our tiny kitchen TV, or of Jimmy Carter’s loss to Ronald Reagan, but honestly, I was a kid and I didn’t pay a lot of attention to current events that didn’t involve comic books or Star Wars action figures.

Forty years on, I remember that fierce sense of wanting to know more, and I reckon that’s kind of stuck with me ever since in my quixotic journey along the margins of journalism.

There’s been a bucketful of tragedies in the 40 years since of course, both personal and global, and one of the knottiest questions of being alive is how we process all the inevitable loss. I never knew the crew of the Challenger of course, and yet it hit a sensitive 14-year-old deep in the chest that clear January day, the brave explorers launching themselves up into the sky and never, ever coming back.