Joe Matt died this week, and he was one of the most fearless and hilarious autobiographical cartoonists of my lifetime.

He was the first of what I think of as the great indie comics creator class of the 1990s to leave us, a group that included the rubbery Gen-X angst of Peter Bagge, the precise skill of Daniel Clowes, the intense surrealism of Chester Brown, the unblinking female gaze of Roberta Gregory and Julie Doucet, the spiralling weirdness and immense talent of Dave Sim and many more.

Matt died – reportedly at his drawing board – of what seems to have been a heart attack at just a week or two past his 60th birthday. He was the creator of the comic book Peepshow, but he hadn’t put out a new comic book since 2006. Yet the work he left behind was hugely influential.

Joe Matt was unafraid to make himself look like an utter asshole, to show all his selfishness and cruelty and self-loathing in his immaculately drawn comics. He wrote himself – or “cartoon Joe” – as a porn addict, hopeless miser and misanthrope, yet his clean, crisp cartooning and willingness to mock himself made it all go down smoothly.

I’ve dabbled in a handful of autobiographical comics and quite a few essays over the years and it’s bloody hard work, to be truly honest, to put that much of yourself on a page.

There were a hundred inferior imitators putting out autobiographical comics in the 1990s and beyond, but Matt, with his bold cartoon lines and comic timing, always stood out.

But then, Joe stopped.

He debuted in the late 1980s with a prolific collection of candid diary comics that showed his rapid improvement in style, but there were just 14 issues of his solo comic Peepshow from 1991 to 2006. Since then, other than sketches and brief strips printed elsewhere, nothing. He wasn’t a recluse by any means, but he just kind of receded from the scene.

That last issue, Peepshow #14, seems hermetic, squalid and a little anguished now. If you zip through all Matt’s unfortunately thin oeuvre, though, it’s a stark change from the friendly but eccentric Joe in his early diary comics to the cranky yet social animal of the early issues to the isolated, obsessed and lonely Joe the final few issues of Peepshow give us, frantically re-editing old pornography tapes into his idea of perfection, obsessing about the girlfriend he broke up with years before, withdrawing more and more into a self-contained shell.

In the weirdly moving final issues, later collected in the graphic novel Spent, Joe Matt seems to show us how much within oneself a man can shrink. Long before Covid, here’s a man undergoing self-isolation. The final few panels of #14 show Joe Matt caked in cat shit (long story), locking himself into a bathroom. And that was it for Peepshow.

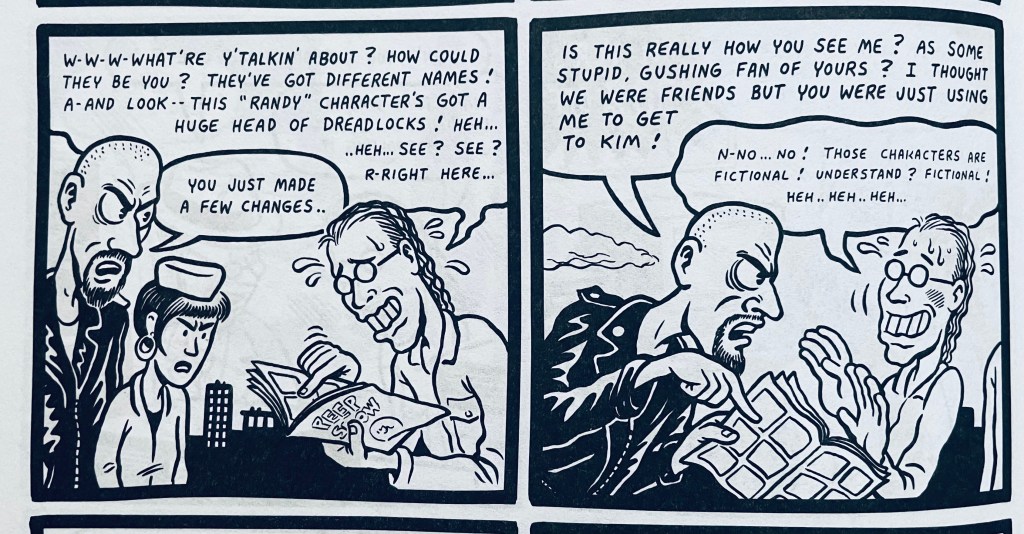

Of course, no autobiography can ever be truly faithful, as they’re bent and twisted in the very shaping. Us fans like to think “Cartoon Joe” was “Real Joe” – but we can never really know. Matt pokes fun at this himself with a scene in Peepshow #6 where an angry boyfriend and girlfriend confront Joe about being put into his comics. Is “real Joe” “cartoon Joe” at all? We will never quite know, now.

In that final issue, Matt flicks back over the previous 13 issues of Peepshow, admitting that a rather fanciful threesome sex scene in one issue was entirely made up, or that the childhood memories in other issues don’t tell the whole story. We invent our autographies.

Yet, Joe Matt did carry on, like many of us, on social media, where he seemed actually, kind of happy whenever I checked in on him, with his beloved cats and spot cartoon panels. I don’t know if he was really the same freaky weirdo he portrayed himself as in Spent, or if he’d regrouped. He apparently had perfected his life to a narrow point of his interests, like we all tend to at a certain age, and while I’d have liked to see Peepshow #15, and #25, and #50, I can’t begrudge him whatever made him happy in the end. Maybe “Cartoon Joe” was just a cartoon after all.

In a fascinating interview from 2013, Matt says of comics, “Consider this: You have 300 pages to work with, and on those pages you can literally depict ANYTHING. You can depict standing in line for a coffee for those entire 300 pages, or you can cover the fictional lives of generations of a small town.” That interview also goes a long way toward explaining why he hadn’t put out anything new in years with his increasing perfectionism.

Supposedly, for years he’d been working on a graphic novel that told the story of his moving from Canada to California, where he spent his final years. I really hope it’s in a shape where someday, we can see it. For a guy who stripped himself literally naked in his work, I think he would’ve wanted it that way.

For all his comic-strip lust, nastiness and obsessions, I still want to know more of Joe Matt’s story, and 60 was just too damn soon to leave us.