How do you write good comics about a being that’s essentially invincible, a force of nature incarnate?

The Spectre is one of those heroes who’s been hanging around DC Comics almost since the beginning. He was introduced in 1940 as hard-as-nails cop Jim Corrigan, who is murdered by criminals but brought back to life given a chance to serve as the “wrath of God,” the Spectre.

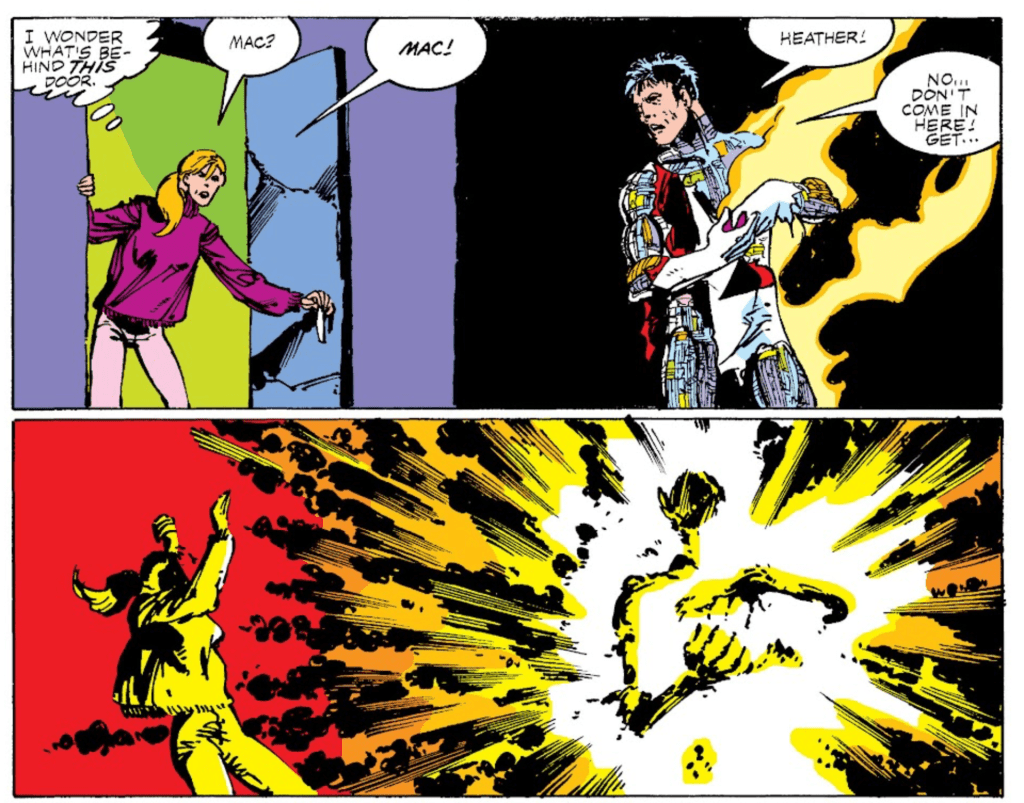

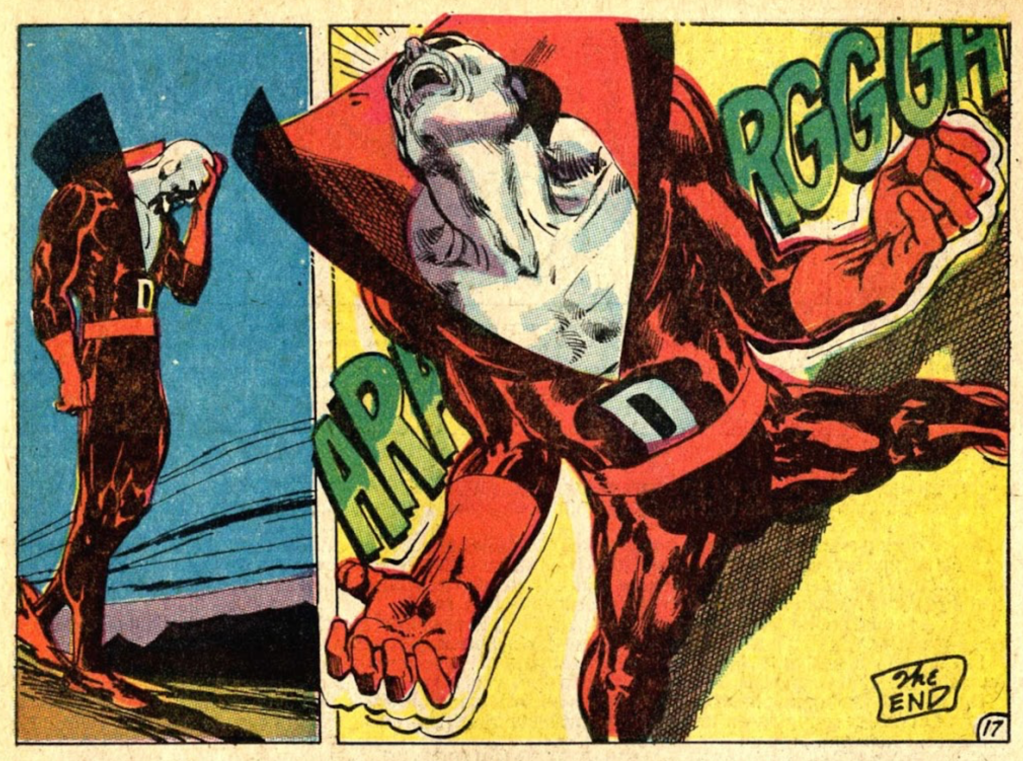

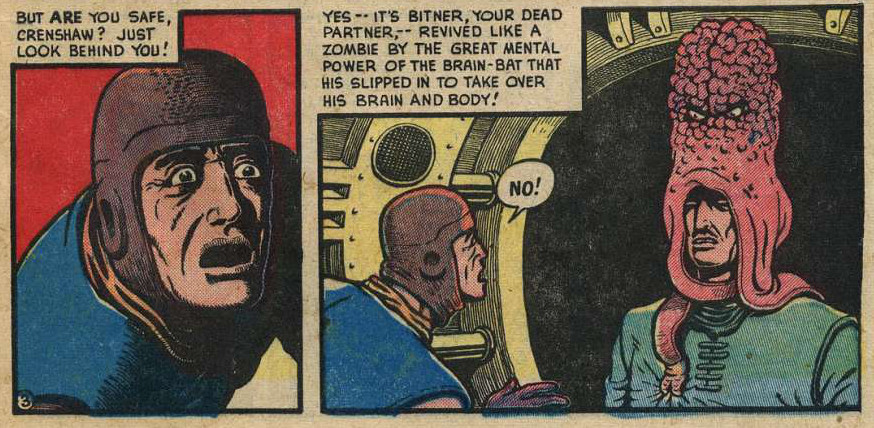

His schtick was punishing criminals in gruesomely inventive ways, such as just full on skeletonising one particularly unlucky bad guy in his very second story:

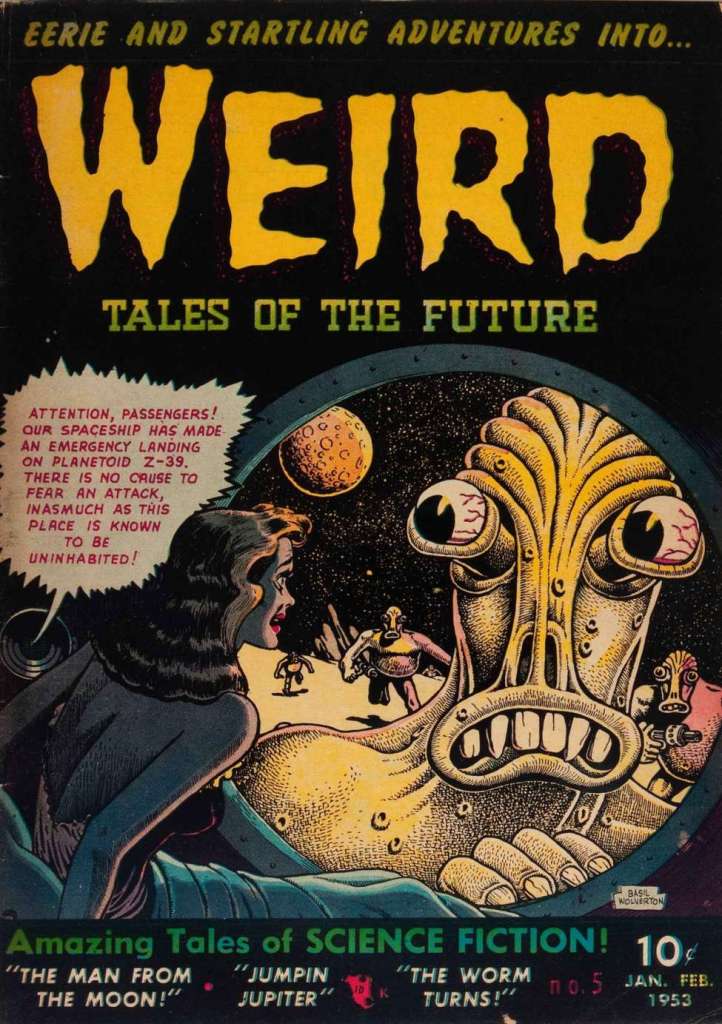

He was made a bit friendlier over time (including a very goofy era when he was basically the sidekick to the dorky “Percival Popp, Super Cop”) and even joined the Justice Society of America, but the Spectre never quite fit in as one of the superhero crowd. He represents something far bigger, more cosmic. When he was brought back in the 1960s, his short-lived solo book had him wrestling bad guys by smacking them in the head with whole planets, because the Spectre always goes hard. But it was hard to make the character relatable when they’re that far beyond humanity, and the run didn’t last long.

I first encountered the Spectre in his brief appearances in Alan Moore’s essential Swamp Thing, where the character was portrayed as an unknowable, awe-inspiring presence, one that reduced your average metahumans to stunned silence.

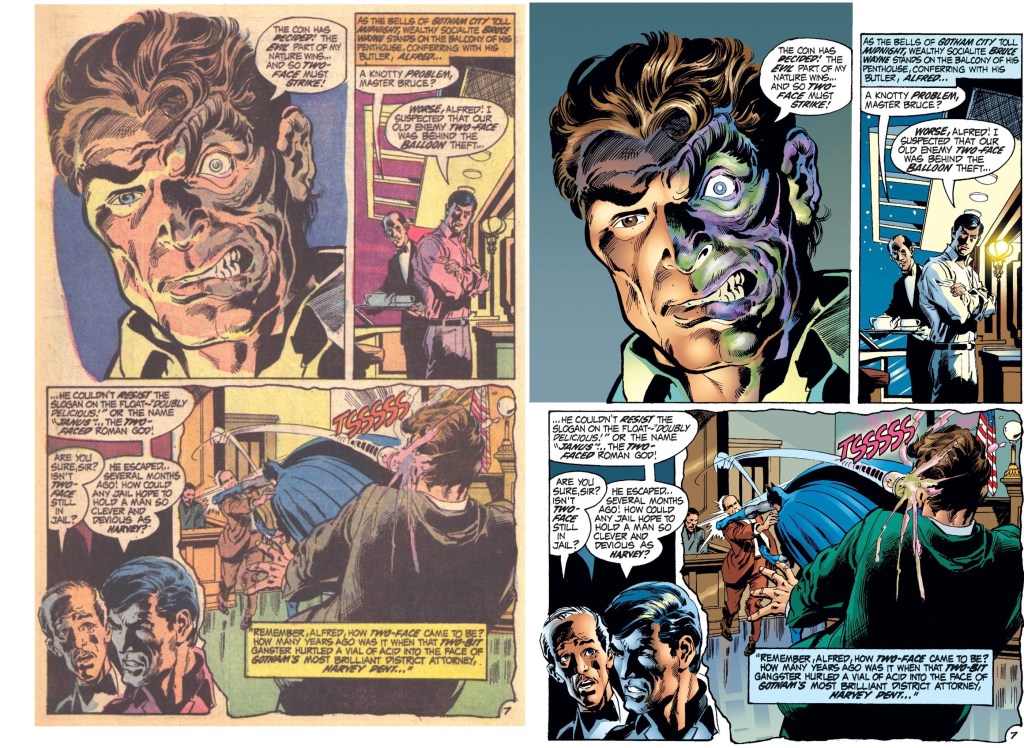

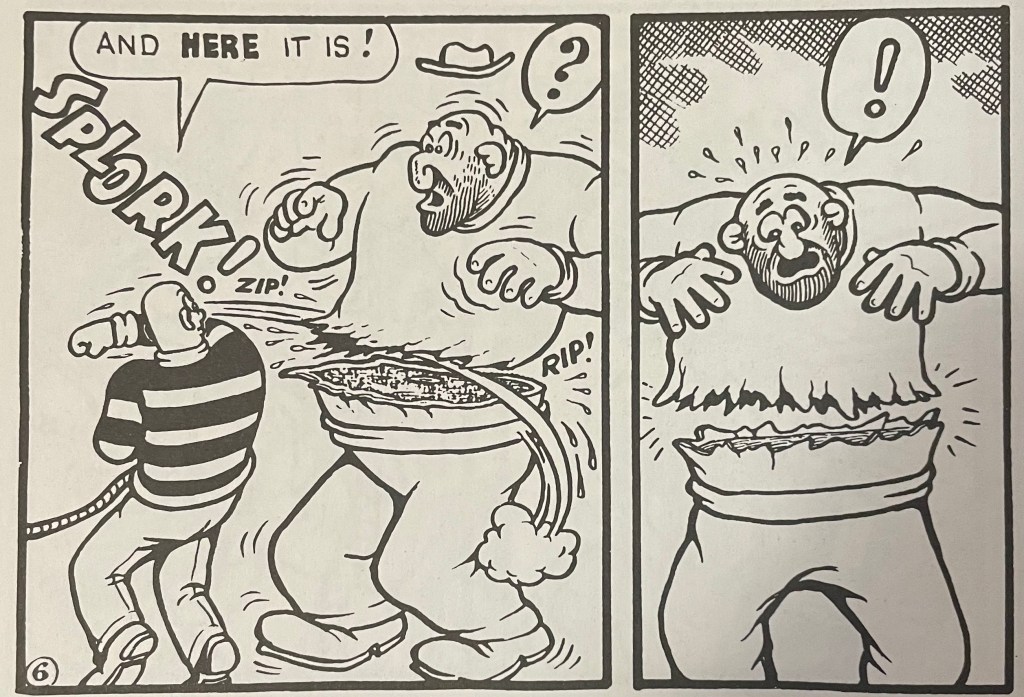

There was also a great short run by Michael Fleisher and Jim Aparo in the 1970s in Adventure Comics which made the Spectre into a full horror movie villain, punishing the guilty with some insanely creative kills – turning a man into wood and putting him through a woodchipper, or chopping him up with giant cartoon scissors, for instance. There wasn’t a lot more to the stories than “how will the Spectre kill this guy?” but they were a lot of gruesome fun.

The problem with the Spectre is how do you really write such a character? “Embodiment of the wrath of God” doesn’t give you a lot of room for nuance. He’s had comics runs that played up the mystic angles and supporting cast and turned him into a kind of Dr. Strange character, but then he just blends into the wallpaper. Some stories had Jim Corrigan definitely part of the Spectre, others had the Spectre as a separate being hosted by Corrigan.

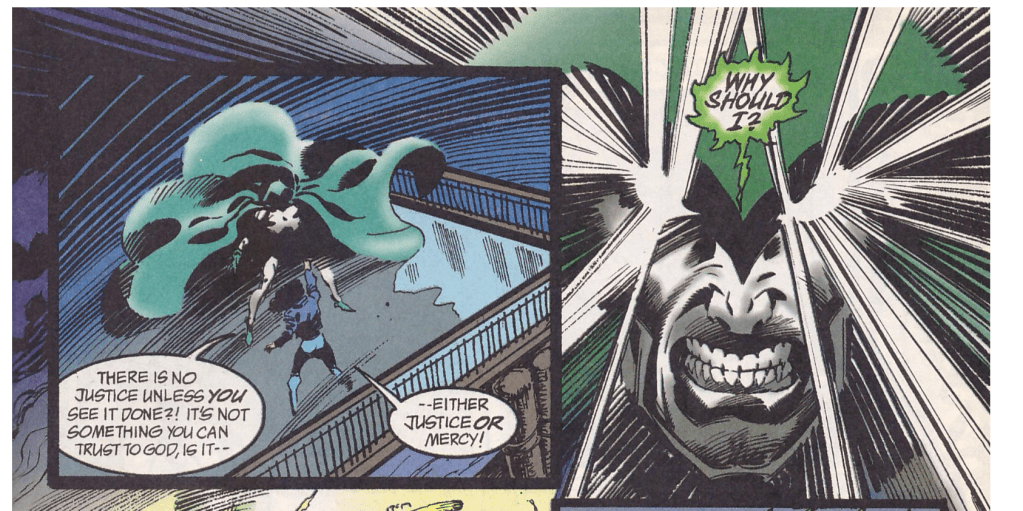

Enter John Ostrander, who married the gnarly punishments with real character work on the Spectre and Jim Corrigan and their peculiar, never-ending bond. His superb 62-issue writing run in the 1990s was peak Spectre, with a comic that was both bombastic and over the top and yet fiercely humane. It embraced the duality of long-dead angry cop Corrigan and the barely contained rage of the Spectre entity for some absolutely banger stories. It richly expands the history of the Spectre entity and its origins in one of the best underrated comics runs – the first half recently was reprinted in an excellent new omnibus.

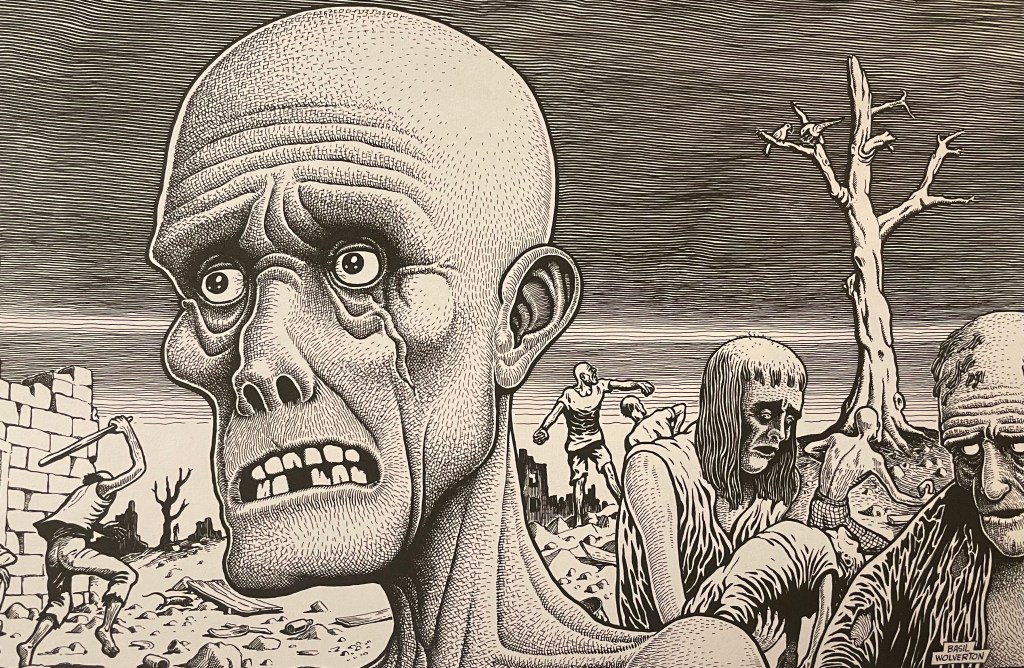

This Spectre run cobbled together all the bits of the character over the years and spun it into a dense, melancholy epic, interrogating again and again what it actually means to be the “wrath of God” and what good vengeance can actually serve. In one story, we see the Spectre brutishly pushing forward to avenge a woman’s murder – in the process driving other innocent people he accuses to suicide.

At one point the Spectre slaughters the population of an entire country torn by civil war – see it as an allegory for the Balkans, or Rwandan genocide – declaring angrily that “no one is innocent!” It’s a key moment that breaks the character free from the giddy righteous cathartic gore of the Fleisher and golden age comics and makes you realise that when you start punishing, it’s pretty hard to stop.

In the end, Ostrander’s Spectre run is about the fluid toxic nature of hate, and how far it can spread and how much it can control even the most cosmic among us.

There’s an operatic excess to Ostrander’s writing, aided by Tom Mandrake’s anguished and dynamic artwork. You can’t go small with the Wrath of God as your lead character. It’s also the rare comics series that actually builds to a firm ending, with Jim Corrigan finally allowed to go on to his reward in the masterpiece last issue. (Of course, being comics, this great ending has been fiddled with a fair bit since that 1998 “last issue,” but it’s still a great story.)

The Spectre hasn’t always been the best fit for good comics and DC is always failing upwards by trying to reinvent the wheel with him (we won’t even talk about that time that, bizarrely, they turned Green Lantern Hal Jordan into a new Spectre for a while), but over the last 85 years, he’s starred in some remarkable stories.

Ostrander’s run is a reminder that you can take a heaven-sent angel of death whose life feels like the chorus to a hundred Black Sabbath songs and still turn it into compelling storytelling. Now, that’s totally metal.