A good film festival is like a church for its acolytes – a place to find solace and enlightenment, to forget your troubles and to imagine exciting new possibilities in life.

A good film festival is like a church for its acolytes – a place to find solace and enlightenment, to forget your troubles and to imagine exciting new possibilities in life.

I’ve been going to the New Zealand International Film Festival every late July and August for more than a decade now, and every year, it’s a highlight of our rainy grey winters. I’m a mere amateur compared to some of the festivalgoers who manage 12, 15, 25 or 30 of the nearly 150 movies that unspool over two weeks or so. This year I’m managing eight, and it’s a spectrum of images and ideas, enough to make me close my eyes at night and dream of red curtains parting to see white screens.

On a Thursday I see documentaries about legendary film critic Pauline Kael and about the Satanic Temple, on a Friday I see a kiwi director’s gory delight, on a Saturday I see a documentary about a meth-addicted magician and on a Sunday I see a pulpy delight of a Korean gangster movie.

On a Tuesday I attend a splendorous red-carpet premiere for a documentary about a Tongan family in New Zealand, which also featured brass bands, Tongan dancers, members of the Tongan royal family and grand and colourful frocks in a dazzling, warm-hearted celebration of New Zealand’s rich Pacific culture. On a Thursday I see Aretha Franklin’s last bow and on a Friday I close it all up with a bizarre-sounding French movie about a man who falls in love with his new jacket.

On a Tuesday I attend a splendorous red-carpet premiere for a documentary about a Tongan family in New Zealand, which also featured brass bands, Tongan dancers, members of the Tongan royal family and grand and colourful frocks in a dazzling, warm-hearted celebration of New Zealand’s rich Pacific culture. On a Thursday I see Aretha Franklin’s last bow and on a Friday I close it all up with a bizarre-sounding French movie about a man who falls in love with his new jacket.

No wonder I can’t stop thinking about movies. It’s a kaleidoscope of cinema every year – in past years I’ve seen grand revivals of Sergio Leone movies, silent classics like “Nosferatu” and Andrei Tarkovsky’s epic, enigmatic Russian epics which demand to be seen on a gaping big screen.

No wonder I can’t stop thinking about movies. It’s a kaleidoscope of cinema every year – in past years I’ve seen grand revivals of Sergio Leone movies, silent classics like “Nosferatu” and Andrei Tarkovsky’s epic, enigmatic Russian epics which demand to be seen on a gaping big screen.

And always something new or novel. Always something that just sounds like it might be interesting, whether it’s a documentary on tea in China or about the band Bikini Kill or a sprawling sci-fi epic or a thriller about zombies taking over a small New Zealand town.

Festivals like this remind me of why I’m so ambivalent about streaming. There’s great things about it, but I hate how it’s slowly eclipsing all other forms of cinema with what feels like an endless flood of cookie-cutter corporate “content.” Try finding more than a few token movies made before 1980 on Netflix. It’s much easier to sit and binge your brain on 12 episodes of some forgettable new show than it is to hunt down and figure out how to watch the greatest hits of a Billy Wilder or Robert Altman.

And while I’m down with the superheroes and the blockbusters there’s something special about gathering in the dark with a film festival crowd, whether it’s a bunch of twisted gorehounds cackling at gruesomely hilarious violence in one movie or an audience full of Tongans roaring at the quirks and jokes of their own closeknit culture.

Film festivals are the bestivals, every year a window into dozens of different worlds all flickering to life on the vast white screen.

I joined a crowd of hundreds to cringe, scream and laugh last night at the premiere of NZ filmmaker

I joined a crowd of hundreds to cringe, scream and laugh last night at the premiere of NZ filmmaker

If I ever was to bottle the essence of my late teenage angst circa ages 16-20, it would smell a lot like Depeche Mode.

If I ever was to bottle the essence of my late teenage angst circa ages 16-20, it would smell a lot like Depeche Mode. Depeche Mode can roughly be broken up into three periods – their lighter “synth pop” phase of the first couple albums, when Erasure’s Vince Clarke was in the band, the “imperial phase” running from roughly “Construction Time Again” to “Ultra” when they pretty much ruled the proto-emo world, and the more muted, less omnipresent latter Mode, after Alan Wilder left the band, which continues pretty much to this day.

Depeche Mode can roughly be broken up into three periods – their lighter “synth pop” phase of the first couple albums, when Erasure’s Vince Clarke was in the band, the “imperial phase” running from roughly “Construction Time Again” to “Ultra” when they pretty much ruled the proto-emo world, and the more muted, less omnipresent latter Mode, after Alan Wilder left the band, which continues pretty much to this day.

The movie begins and ends with sepia tones, homaging an imagined western past that America has fetishised for decades. But in between “Butch Cassidy” is a determinedly modern movie, with Joss Whedon-worthy jokes being cracked left and right by Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Rather than the stoic masculine glares of an Eastwood or John Wayne, you’ve got Paul Newman’s motormouth Butch, whose first act of violence in the film isn’t a grim showdown – it’s kicking someone in the nuts. Meanwhile, Robert Redford’s Sundance Kid is the more traditional hero of the two, but he still shows cracks in his western hero facade.

The movie begins and ends with sepia tones, homaging an imagined western past that America has fetishised for decades. But in between “Butch Cassidy” is a determinedly modern movie, with Joss Whedon-worthy jokes being cracked left and right by Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Rather than the stoic masculine glares of an Eastwood or John Wayne, you’ve got Paul Newman’s motormouth Butch, whose first act of violence in the film isn’t a grim showdown – it’s kicking someone in the nuts. Meanwhile, Robert Redford’s Sundance Kid is the more traditional hero of the two, but he still shows cracks in his western hero facade. “Butch Cassidy” is one of those pivotal movies of the ‘60s and ‘70s that forever cracked the old of the traditional heroic figure. The reason it still seems so relaxed today is that we’ve been surrounded by Butch and his offspring for years. Long may they ride.

“Butch Cassidy” is one of those pivotal movies of the ‘60s and ‘70s that forever cracked the old of the traditional heroic figure. The reason it still seems so relaxed today is that we’ve been surrounded by Butch and his offspring for years. Long may they ride. I hadn’t been to Christchurch in 10 years, and I’m not quite sure how that happened.

I hadn’t been to Christchurch in 10 years, and I’m not quite sure how that happened. The signs of the 2011 earthquakes are everywhere, far more prevalent than I’d imagined they’d be almost a decade on. Downtown is dotted with vacant lots, cranes constructing new buildings, and the cracked and battered abandoned remains of those structures that haven’t been torn down yet. For every building that seems fine, there’s another that’s a dust-covered shell that looks like something from Chernobyl. The gorgeous old Christchurch Cathedral is a broken and gaping maw, like a dollhouse cross-section where you can see inside a building. Dozens of pigeons still nest in the rafters, visible to all.

The signs of the 2011 earthquakes are everywhere, far more prevalent than I’d imagined they’d be almost a decade on. Downtown is dotted with vacant lots, cranes constructing new buildings, and the cracked and battered abandoned remains of those structures that haven’t been torn down yet. For every building that seems fine, there’s another that’s a dust-covered shell that looks like something from Chernobyl. The gorgeous old Christchurch Cathedral is a broken and gaping maw, like a dollhouse cross-section where you can see inside a building. Dozens of pigeons still nest in the rafters, visible to all.

What, me sorry? The rumours are flying fast and furious that

What, me sorry? The rumours are flying fast and furious that  Soon I also discovered “classic” MAD, the Harvey Kurtzman-edited comic book that the magazine originally began as in 1952. It remained the last gasp of EC Comics itself after the great comics-will-warp-you scare of the ‘50s shut the rest of the line down. I got a massive volume collecting #1-6 of the series, packed with Kurtzman wit, Will Elder’s insanely detailed art, Wally Wood’s gorgeous spacemen and girls, and much more. I still have that somewhat battered gorgeous big volume of MAD’s first 6 issues, along with several other volumes collecting the original series, plus scattered around the house a battered stack of issues dating back to the ‘70s, all well-read and mangled as they should properly be.

Soon I also discovered “classic” MAD, the Harvey Kurtzman-edited comic book that the magazine originally began as in 1952. It remained the last gasp of EC Comics itself after the great comics-will-warp-you scare of the ‘50s shut the rest of the line down. I got a massive volume collecting #1-6 of the series, packed with Kurtzman wit, Will Elder’s insanely detailed art, Wally Wood’s gorgeous spacemen and girls, and much more. I still have that somewhat battered gorgeous big volume of MAD’s first 6 issues, along with several other volumes collecting the original series, plus scattered around the house a battered stack of issues dating back to the ‘70s, all well-read and mangled as they should properly be. MAD ended its 550-issue run and “relaunched” like pretty much every other long-running comic book publication about a year ago, and the writing was on the wall then. But to be honest, in the age of Trump, isn’t everything feeling a little satirical? When Trump himself made fun of presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg by saying he ‘looked like Alfred E. Neuman,” nobody under 40 really seemed to get the the joke, including the candidate himself.

MAD ended its 550-issue run and “relaunched” like pretty much every other long-running comic book publication about a year ago, and the writing was on the wall then. But to be honest, in the age of Trump, isn’t everything feeling a little satirical? When Trump himself made fun of presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg by saying he ‘looked like Alfred E. Neuman,” nobody under 40 really seemed to get the the joke, including the candidate himself. What is it: The world’s most famous demonic possession story, the 1973 horror classic

What is it: The world’s most famous demonic possession story, the 1973 horror classic  It makes what follows later that much more profane and shocking. And the movie’s most iconic moments – the possession of Regan and her gruesome actions – are still truly horrifying today. Every parent of a teenager has that moment of disconnection when your child suddenly seems like an alien to you, and “The Exorcist” dramatises that perfectly to terrible extremes.

It makes what follows later that much more profane and shocking. And the movie’s most iconic moments – the possession of Regan and her gruesome actions – are still truly horrifying today. Every parent of a teenager has that moment of disconnection when your child suddenly seems like an alien to you, and “The Exorcist” dramatises that perfectly to terrible extremes.

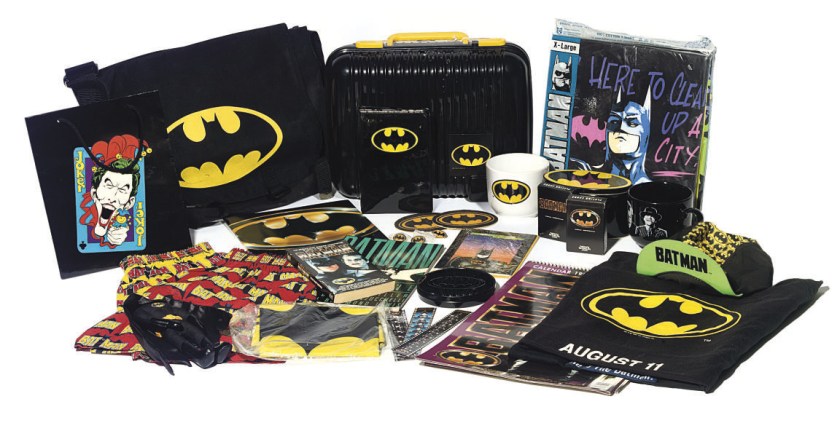

Thirty years ago today, I was standing in a line. A bunch of us were all queued up for what was then the biggest comic book movie of all time, Tim Burton’s Batman.

Thirty years ago today, I was standing in a line. A bunch of us were all queued up for what was then the biggest comic book movie of all time, Tim Burton’s Batman. It’s hard to explain to fans of today’s slick, streamlined and gorgeous Marvel Universe movies that seeing a comic book movie in the ‘80s and ‘90s was mostly a matter of lowering expectations, of accepting flaws and looking for the bits that worked.

It’s hard to explain to fans of today’s slick, streamlined and gorgeous Marvel Universe movies that seeing a comic book movie in the ‘80s and ‘90s was mostly a matter of lowering expectations, of accepting flaws and looking for the bits that worked. But Keaton’s Batman has only grown in strength over the years. He never quite has the classic physical profile – seen in a tuxedo in an early scene, his Bruce Wayne’s shoulders would barely fill half the Bat-suit – but acting is often concentrated in the eyes, and Keaton’s eyes hold a balance of resolve and regret. His Bruce Wayne seems closer to the edge than some – look at the scene where he takes on the Joker in his civilian clothes: “You want nuts? Let’s get nuts!” In contrast, his Batman is more of a blank, grim slate, a mask that wipes out Wayne’s humanity and focuses his mission.

But Keaton’s Batman has only grown in strength over the years. He never quite has the classic physical profile – seen in a tuxedo in an early scene, his Bruce Wayne’s shoulders would barely fill half the Bat-suit – but acting is often concentrated in the eyes, and Keaton’s eyes hold a balance of resolve and regret. His Bruce Wayne seems closer to the edge than some – look at the scene where he takes on the Joker in his civilian clothes: “You want nuts? Let’s get nuts!” In contrast, his Batman is more of a blank, grim slate, a mask that wipes out Wayne’s humanity and focuses his mission.