What is it: Like most people who’ve found themselves somewhat against the grain in life, I dig The Rocky Horror Picture Show. It’s pretty much the definition of a cult classic, still playing in midnight shows around the world 44 years after its 1975 release. Seeing it in a vintage theatre in high school was one of my great cultural awakenings, and fittingly, I saw it again in a theatre just this past Halloween in a terrific benefit showing here in Auckland, complete with New Zealander creator, writer and co-star Richard “Riff Raff” O’Brien in attendance. I don’t do the costumes – nobody wants to see me in fishnets – but there’s something truly wonderful about a Rocky Horror screening, with everyone flying their own personal freak flag and screaming crazy stuff at the screen for a bizarre little film that somehow sticks with you.

And then there’s Shock Treatment. Shock Treatment is the little-known 1981 quasi-sequel to Rocky Horror, again written by O’Brien and directed by Jim Sharman. It’s loosely the tale of Brad and Janet (recast, woefully) taking part in a surreal TV game show experience and being “reinvented” into superstars. But in execution, it’s kind of a mess.

Why I never saw it: Even today, Shock Treatment is pretty obscure. My main vague memory of it was the cool, eye-catching poster design (above). You can find it with a bit of searching on YouTube, though.

Does it measure up to its rep? Disappointingly, yes. Shock Treatment is a film that isn’t quite sure what it’s trying to say. You can’t really create a cult hit when you’re trying so hard to. Shock Treatment is a muddle of early ‘80s glam-pop, a satire of reality TV, and a tale of empowerment. Unfortunately, it’s a little too similar to Rocky Horror in that it’s again a tale of Brad and Janet finding their bliss. Unlike Rocky Horror’s smooth, straightforward plot, a mish-mash of horror movie cliches, Shock Treatment is maddeningly hard to follow.

A charismatic foil like Tim Curry is badly missed here, although O’Brien’s creepy Dr. Cosmo is one of the better things about the movie, but he’s not in it enough. Rocky Horror stars Patricia Quinn, Charles ‘No Neck’ Gray and Little Nell also show up in small roles. Recasting Brad and Janet was a bad idea (bizarrely, the events of Rocky Horror are never mentioned, leading you to wonder if it’s a reboot or a prequel or what). Jessica Harper is a very stiff Janet who only comes to life in the movie’s final act, while Cliff De Young’s Brad Majors is awful – his entire performance is lacking the wit and insight Barry Bostwick’s Brad brought to a single line in Rocky Horror: “It’s beyond me / Help me mommy.”

All in all, Shock Treatment feels too much like hard work. Many of the songs are pretty enjoyable, but like most of the movie, they’re overproduced and chaotic. Rocky Horror is a strange beast of a film too, but it’s consistent and genuinely warm at times. Shock Treatment never invites you in, and you never feel like you want to shout back at the screen.

How’s it different than I thought: While it’s wacky and strange, Shock Treatment is never as transgressive as Rocky Horror. It mocks lots of things, like Reagan’s America and TV game shows, but it never really bares its fangs.

Worth seeing? If you’re a die-hard Rocky Horror fan, it’s worth checking out. Once. But nobody’s going to be throwing rice at the screen for this one.

I’m a fan of a lot of things. But “Star Wars” is complicated for me.

I’m a fan of a lot of things. But “Star Wars” is complicated for me.

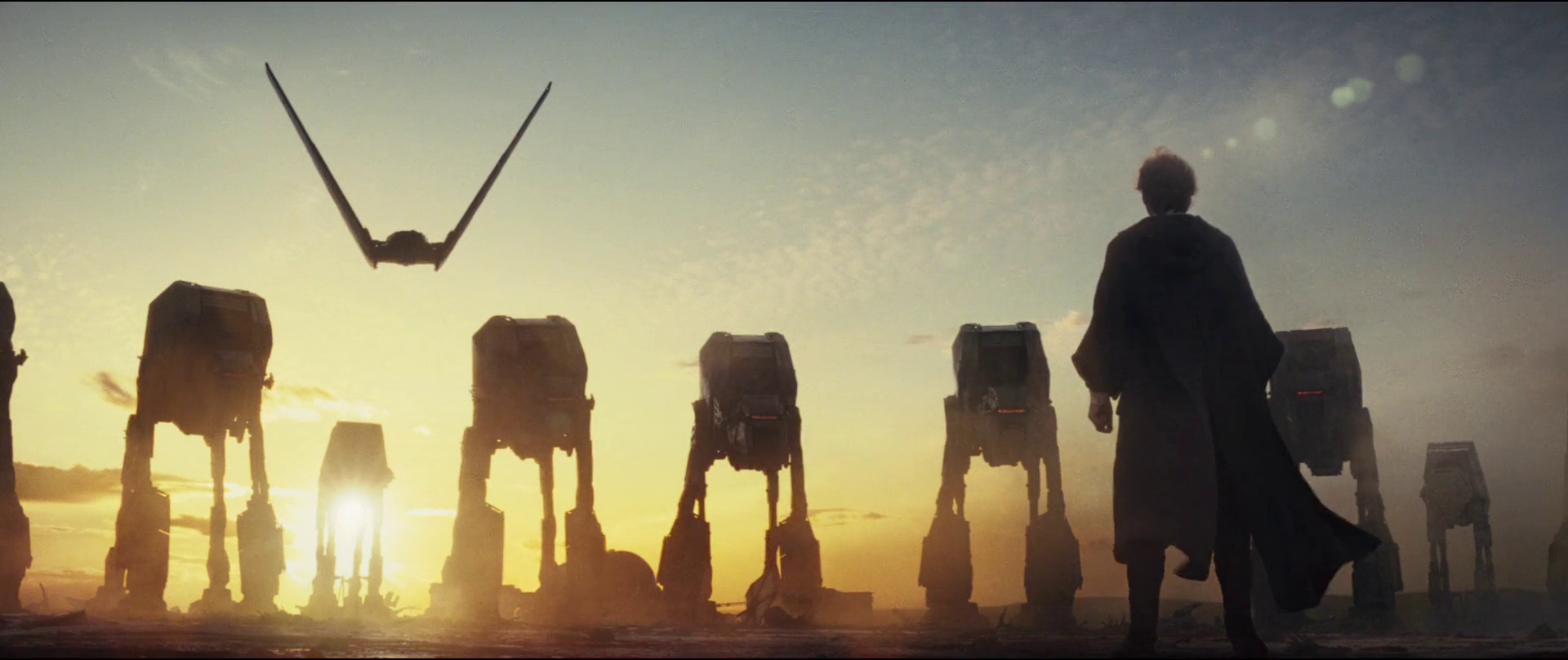

I watched “The Last Jedi” again recently, and it’s the rare post-1983 “Star Wars” movie that actually gets better on each viewing. It goes in hard, unexpected places and objectively speaking is the most beautiful movie of the entire series to date, with director Rian Johnson composing painterly, stunning vistas that remind me of why I fell in love with the alien skies of Tatooine and Bespin in the first place. The cast is great (sorry, keyboard warriors) and it’s honestly the most surprising “Star Wars” movie since “Empire Strikes Back.”

I watched “The Last Jedi” again recently, and it’s the rare post-1983 “Star Wars” movie that actually gets better on each viewing. It goes in hard, unexpected places and objectively speaking is the most beautiful movie of the entire series to date, with director Rian Johnson composing painterly, stunning vistas that remind me of why I fell in love with the alien skies of Tatooine and Bespin in the first place. The cast is great (sorry, keyboard warriors) and it’s honestly the most surprising “Star Wars” movie since “Empire Strikes Back.”

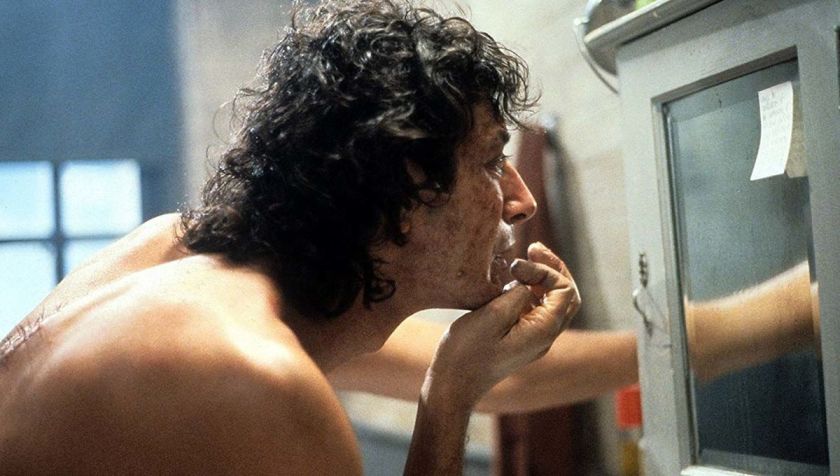

What is it: It’s not exactly a household name, but in certain circles, it’s the holy bible of cheesy kung-fu schlock.

What is it: It’s not exactly a household name, but in certain circles, it’s the holy bible of cheesy kung-fu schlock.  Does it measure up to its rep? This is

Does it measure up to its rep? This is  How’s it different than I thought: Unlike the

How’s it different than I thought: Unlike the  A good film festival is like a church for its acolytes – a place to find solace and enlightenment, to forget your troubles and to imagine exciting new possibilities in life.

A good film festival is like a church for its acolytes – a place to find solace and enlightenment, to forget your troubles and to imagine exciting new possibilities in life.

No wonder I can’t stop thinking about movies. It’s a kaleidoscope of cinema every year – in past years I’ve seen grand revivals of Sergio Leone movies, silent classics like “Nosferatu” and Andrei Tarkovsky’s epic, enigmatic Russian epics which demand to be seen on a gaping big screen.

No wonder I can’t stop thinking about movies. It’s a kaleidoscope of cinema every year – in past years I’ve seen grand revivals of Sergio Leone movies, silent classics like “Nosferatu” and Andrei Tarkovsky’s epic, enigmatic Russian epics which demand to be seen on a gaping big screen. I joined a crowd of hundreds to cringe, scream and laugh last night at the premiere of NZ filmmaker

I joined a crowd of hundreds to cringe, scream and laugh last night at the premiere of NZ filmmaker

The movie begins and ends with sepia tones, homaging an imagined western past that America has fetishised for decades. But in between “Butch Cassidy” is a determinedly modern movie, with Joss Whedon-worthy jokes being cracked left and right by Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Rather than the stoic masculine glares of an Eastwood or John Wayne, you’ve got Paul Newman’s motormouth Butch, whose first act of violence in the film isn’t a grim showdown – it’s kicking someone in the nuts. Meanwhile, Robert Redford’s Sundance Kid is the more traditional hero of the two, but he still shows cracks in his western hero facade.

The movie begins and ends with sepia tones, homaging an imagined western past that America has fetishised for decades. But in between “Butch Cassidy” is a determinedly modern movie, with Joss Whedon-worthy jokes being cracked left and right by Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Rather than the stoic masculine glares of an Eastwood or John Wayne, you’ve got Paul Newman’s motormouth Butch, whose first act of violence in the film isn’t a grim showdown – it’s kicking someone in the nuts. Meanwhile, Robert Redford’s Sundance Kid is the more traditional hero of the two, but he still shows cracks in his western hero facade. “Butch Cassidy” is one of those pivotal movies of the ‘60s and ‘70s that forever cracked the old of the traditional heroic figure. The reason it still seems so relaxed today is that we’ve been surrounded by Butch and his offspring for years. Long may they ride.

“Butch Cassidy” is one of those pivotal movies of the ‘60s and ‘70s that forever cracked the old of the traditional heroic figure. The reason it still seems so relaxed today is that we’ve been surrounded by Butch and his offspring for years. Long may they ride.