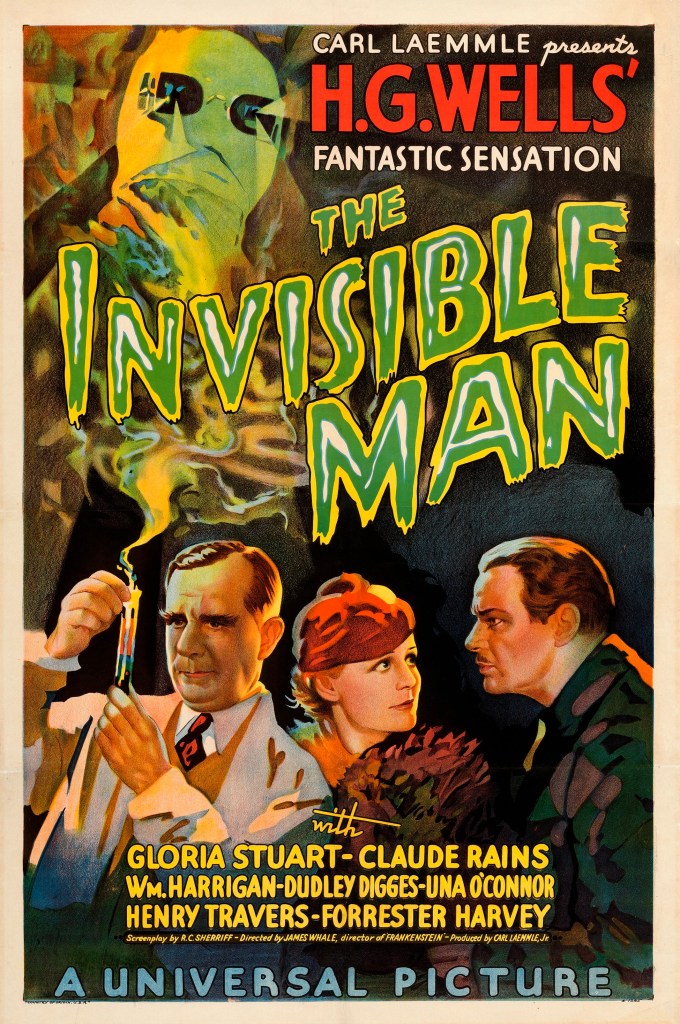

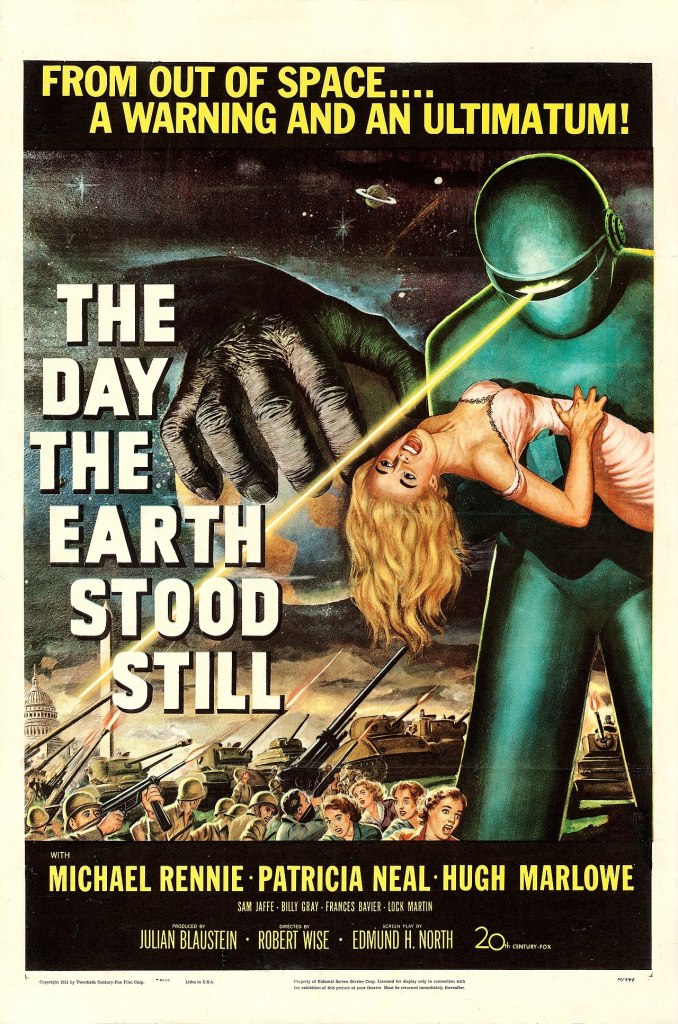

What is it? The plot is simple: A peaceful alien arrives on Earth to deliver an important message, but is immediately met by fear and hatred. It’s an idea that’s been revisited countless times everywhere from E.T. to Starman to Arrival, but seldom with quite as much cool style as in 1951’s The Day The Earth Stood Still. Michael Rennie plays Klaatu, a seemingly human alien who arrives on Earth with an ominous robot sidekick, Gort, and who attempts to understand humanity. Klaatu grows close to an Earth boy and his mother, but fears that Earth’s warring nuclear powers threaten the rest of the universe’s stability.

Why I never saw it: Some movies seep into the collective unconsciousness so much, you think you have seen them. Any somewhat movie-literate person recognises the image of Gort emerging from Klaatu’s spaceship. Yet when I was a teenager discovering all those old ‘50s sci-fi classics, this one wasn’t on the afternoon TV movie rotations. Somehow, the movie itself had slipped through my watchlist over the years but because it is so familiar, watching it felt a bit like rediscovering an old book you read and loved long ago.

Does it measure up to its rep? From the creepy theremin soundtrack to the bold and simple iconic designs of Klaatu’s flying saucer and Gort’s lurking menace, Day The Earth Stood Still is a template for what we think of when we think of smart science fiction. Don’t overlook Rennie’s quietly charismatic performance as Klaatu, one of the first of many cinematic “strangers in a strange land” to ponder the mysteries of us earthlings. Rennie anchors the movie when it threatens to dissolve into kitsch or sentiment (Keanu Reeves played the role in a widely ignored 2008 remake, which I haven’t seen). Sure, Klaatu’s relationship with naive little Earth child Bobby is a plot device that is a bit saccharine, but Patricia Neal’s thoroughly humane performance as his mother works very well, especially as she comes into her own in the final act.

The 1950s were an absolute golden age for science fiction movies. Sure, they had existed before that and SF’s roots date back at least to the Victorian work of Jules Verne, but in the devastated aftermath of World War II, SF became a way for us to work out our feelings about the brave new world of atomic energy, mass death and the cosmic unknown.

Anyone who calls themselves a science fiction fan has at least a few ‘50s movies they love, from the original Godzilla to the creepy creatures of The Blob, The Thing and Them to the more thoughtful, contemplative vibe of classics like Forbidden Planet, The Incredible Shrinking Man and War Of The Worlds. The Day The Earth Stood Still stands firmly in that company, as science fiction that asks questions and makes us question our own beliefs. It’s ahead of its time and thoroughly of its time all at once.

Worth seeing? Absolutely, because while the cold war paranoia that coursed through the bloodstream of so much 1950s science fiction has eased a bit, the movie’s message hasn’t lost relevance. We humans are still self-destructive, often brutish creatures determined to sabotage our world’s possibilities, as the last few years have so thoroughly reminded us. When Klaatu says at the end, “the decision rests with you,” that’s a message that resounds still 70 years on. Hopefully eventually we’ll listen.