It’s been a week for movies and the media. I was part of the team live-blogging the Oscars over at RNZ this week which, um, took an interesting turn about 2/3 of the way into the show, you might have heard.

I love it when one of my favourite things, the movies, intersects with my profession for many years now, journalism. And after the Oscars live-blogging marathon Monday night, I had to unwind with one of my favourite movies about journalism (which one? scroll to the end*, my friend).

The art and craft of journalism has long fascinated filmmakers and resulted in some terrific movies – including that one many people regard as the best of all time, Citizen Kane. I sat down to write about 10 or so of my favourite journalism movies and ended with a sprawling list. I narrowed it down, and from the start I eliminated any documentaries (which are a form of journalism itself). Ever since I was a kid, the idea of journalism has appealed to me, even if in real life it’s not all glam and scoops.

This list of my Top 10 Journalism Movies includes ones that idealise the profession like crazy, ones that just use it as a prop for a comedy or a romance, and a few that really delve into the gritty hard yards that make a truly great story. Some of them really capture what it’s like to be a journo, and some of them really capture what we all wish it was like to be a journo.

In alphabetical order:

Ace In The Hole (1951) – The late great Kirk Douglas in his finest role, as a cartoonishly conniving tabloid journalist exiled to the rural sticks who stumbles on the “story of the century” when a local man gets trapped in a cave. Billy Wilder’s cynical noir takes us deep inside the media circus that ensues, and we watch in real time as Kirk’s Chuck Tatum slowly loses what’s left of his soul. We’ve had countless “boy stuck in a well” type media sensations in the decades since, but nothing has ever captured the dark side of journalism better.

All The President’s Men (1976) – There’s no way any list of journalism movies could ignore this one. Oh, for the days when Watergate was the biggest scandal a White House could imagine. There’s no movie that shows the painstaking, frustrating detective side of journalism better than this masterpiece, with Woodward and Bernstein’s investigations portrayed with stark realism despite glossy Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman playing their parts. The click of typewriters and hours on the landline phone, the endless cigarettes, the newsroom almost entirely run by white men wearing ties – this is a vanished world now, and journalism is probably better for leaving a lot of that behind, but nothing quite captures what it was like “back in the day” better than this film.

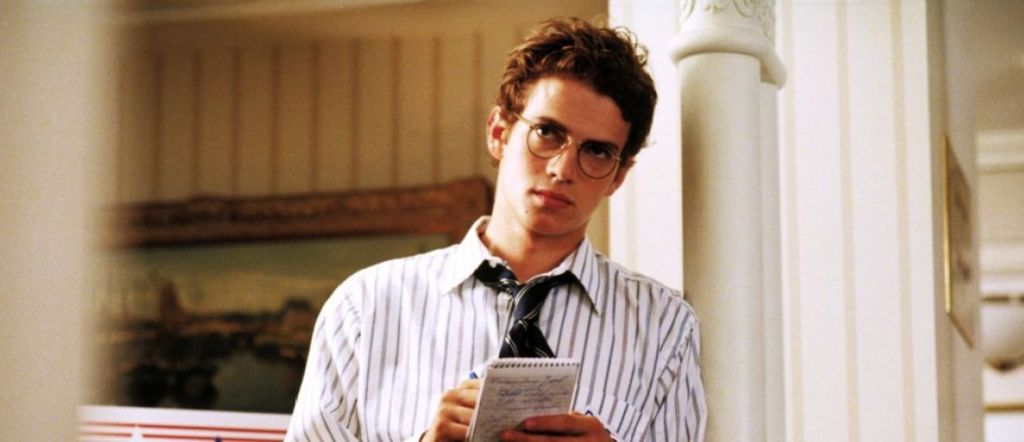

Almost Famous (2000) – The life that William Miller leads in Cameron Crowe’s gentle and bittersweet coming-of-age comedy is pretty much exactly the life I imagined I might have when I started scribbling as an entertainment journalist in the mid 1990s. Spoiler: I didn’t go on tour with Stillwater or fall in love with Penny Lane. Crowe’s movie is warmly sentimental, but in the best possible way. With the acerbic interjections of the much-missed Philip Seymour Hoffman’s Lester Bangs to balance things out, Almost Famous shows us a fairy-tale fantasy of journalism that I can’t help falling in love with every time I watch it.

Anchorman (2004) – Absurdly goofy? Sure! The gem in Will Ferrell’s run of wacky comedies is a spoof of journalism, but it’s also subtly a very accurate satire of the alpha-male mentality that existed in newsrooms for decades, one that was still quite rampant just as I was entering the industry. It’s only in the last few decades that newsrooms have become a bit more diverse, and in between all the gags Anchorman accurately captures what it’s like when journalists start to believe their own hype and let their ego take over. (See also: Any number of the ‘outrage merchants’ who chatter and moan daily on American news networks today.)

Broadcast News (1987) – The great journalism romantic comedy, even beating out Cary Grant’s His Girl Friday. The late William Hurt, Holly Hunter and Albert Brooks are a perfect trio of striving TV journalists in the 1980s, capturing the mix of solid professionalism, glossy vapid good looks and gender battles that defined the era. James L. Brooks carefully keeps all his characters human despite their foibles, and it’s a movie that’s as much in love with journalism and it gently mocks it. And for my money, the “Albert Brooks sweating” scene is one of the funniest journalism fails ever portrayed on screen.

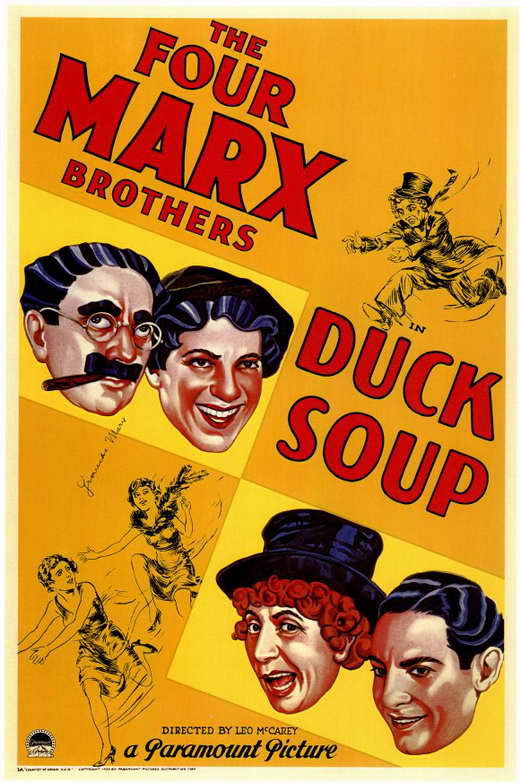

Citizen Kane (1941) – The grandfather of all journalism movies, even if it’s perhaps more about the corruption of power than anything else. But Orson Welles captures the era when news publishers were almost kings in his very lightly fictionalised take on William Randolph Hearst, and how Kane uses the immense power of the press to build himself a perfect world – without ever really knowing what to do once he gets it.

The French Dispatch (2021) – The newest movie on this list, Wes Anderson’s kaleidoscopic anthology imagines a series of articles in a New Yorker-type magazine in its final issue. Anderson’s unique aesthetic has never been more pronounced than it is in this incredibly dense, ornate movie, which I immediately wanted to see a second time so I could go back and catch all the jokes and references I missed the first time around.

Shattered Glass (2003) – For a while there in the pre-social media world, scandals about plagiarist journalists were all the rage. This tense and darkly funny under-seen gem looks at the curious Stephen Glass, who made up magazine scoops left and right until he was caught. Featuring a never-better performance by Hayden Christensen, who will wipe your memories entirely of his hammy Anakin Skywalker, and terrific work by Peter Sarsgaard as the editor who exposes him.

Spotlight (2015) – A solid companion to All The President’s Men, set at the twilight of a certain kind of journalism, before job cuts gutted newsrooms worldwide. This deserving Oscar winner showcases a Boston investigative journalists team and their stunning work uncovering sex abuse cover-ups within the Catholic Church. With an absolutely top-notch cast including Michael Keaton, Mark Ruffalo and Liev Schreiber, it’s another movie that patiently shows the hard, hard work that goes into breaking a massive story, and yet makes it exciting as any thriller.

Zodiac (2007) – When journalism turns into obsession. David Fincher’s sprawling, sinister epic about the hunt for San Francisco’s Zodiac killer avoids tidy serial murder movie cliches or easy closure, and somehow that makes it even more disturbing than any blood-soaked horror might. Robert Downey Jr., Jake Gyllenhaal and Mark Ruffalo are terrific as journalists who slowly lose their minds trying to find a killer, and Fincher masterfully escalates a sense of dread, which is inextricably tied to the one single question that drives almost every journalist’s career: I want to know.

Clustered together at #11: His Girl Friday, The Sweet Smell of Success, Fletch, The Paper, Good Night And Good Luck, The Philadelphia Story, Adaptation, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

(*So what did I watch after Oscars live-blogging? Well, after a night that hit the peaks of drama and absurdity, what else could I watch but Anchorman for the 458th time? What can I say … sometimes journalism really is like being trapped in a glass case of emotion.)