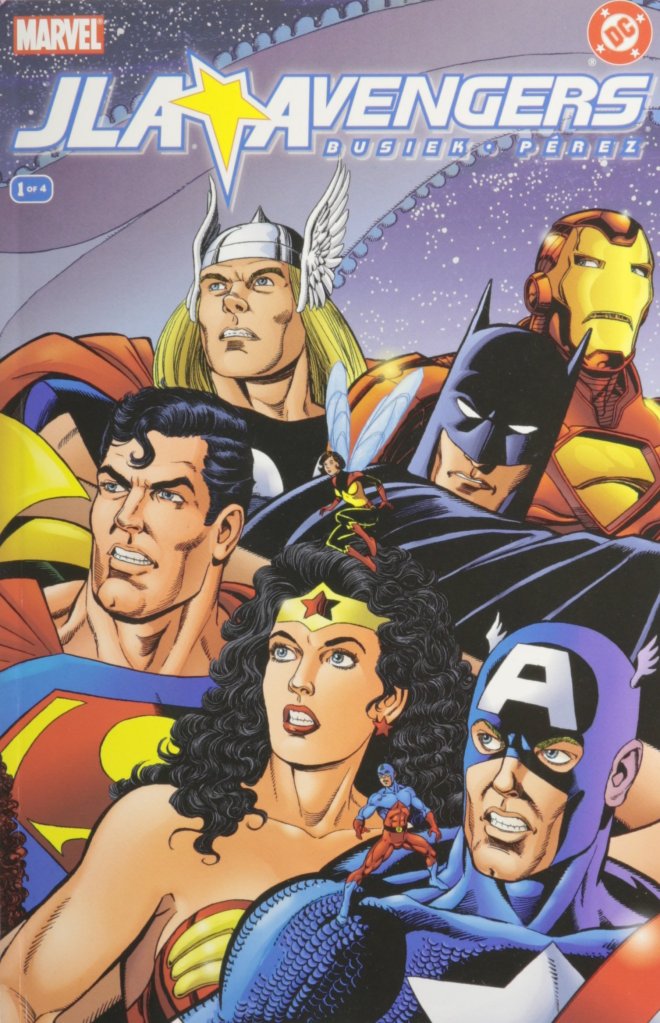

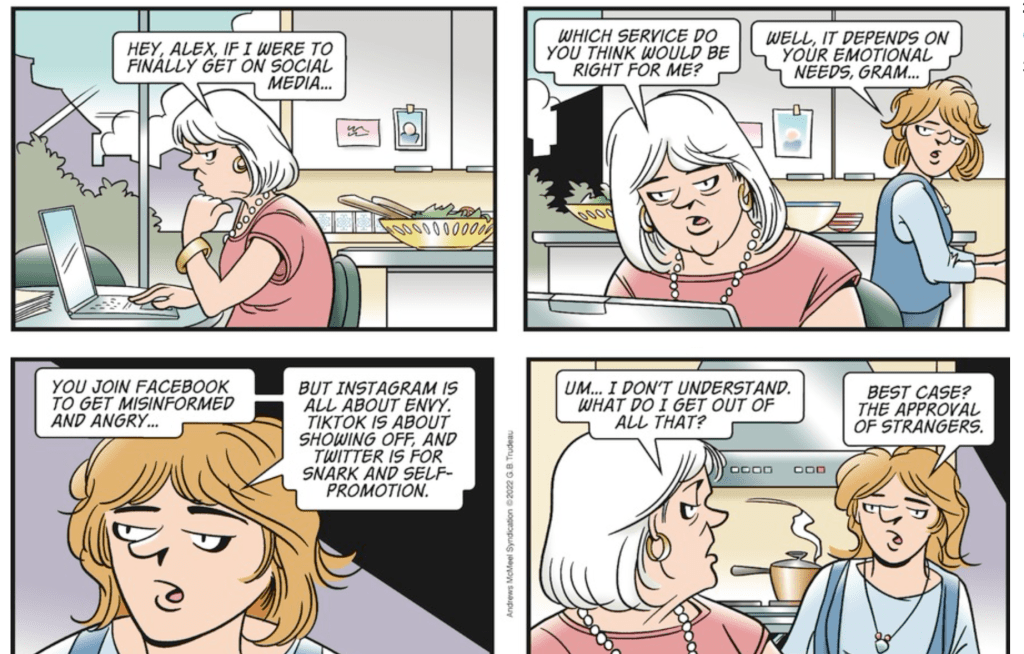

The problem with never-ending serialised fiction is just that – it never ends. Unless a meteor finally hits the planet, you’ll probably never really see a truly final adventure of Superman, Spider-Man or Batman. Sure, there’s plenty of possible final stories and alternative histories out there – but the powers that be will never let the underlying intellectual property go truly dormant.

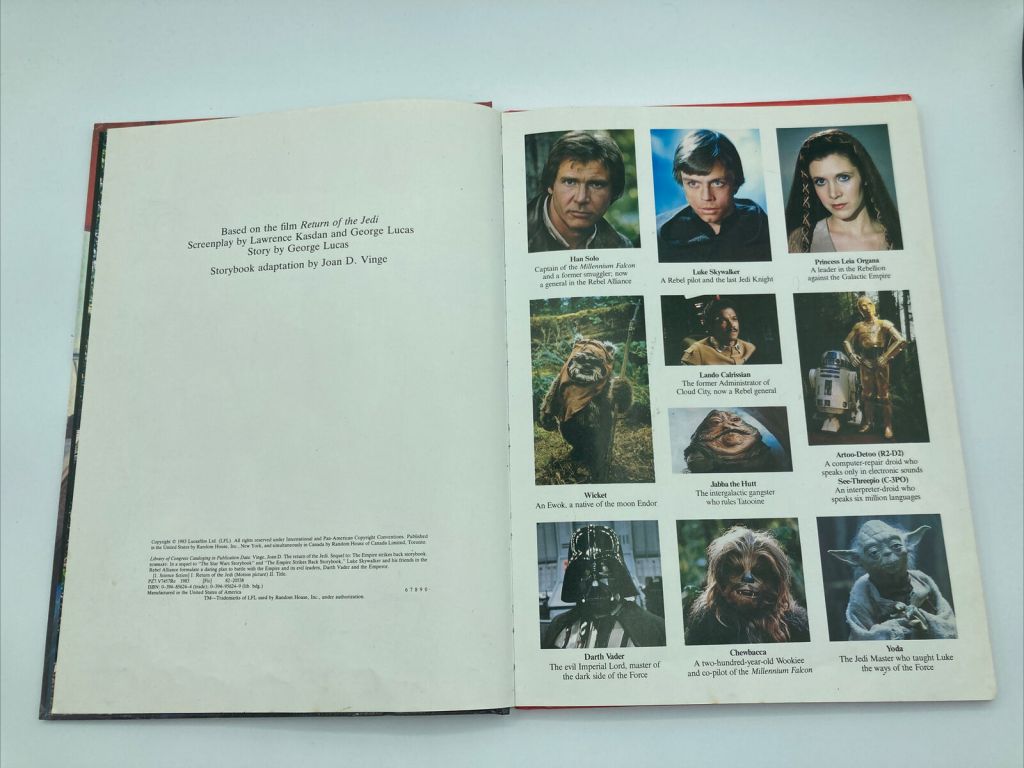

Heck, even stories we once thought were over, such as Star Wars circa 1985, have been prequeled and sequeled and sidequeled and likely will until they run out of steam until the inevitable next reboot circa 2045.

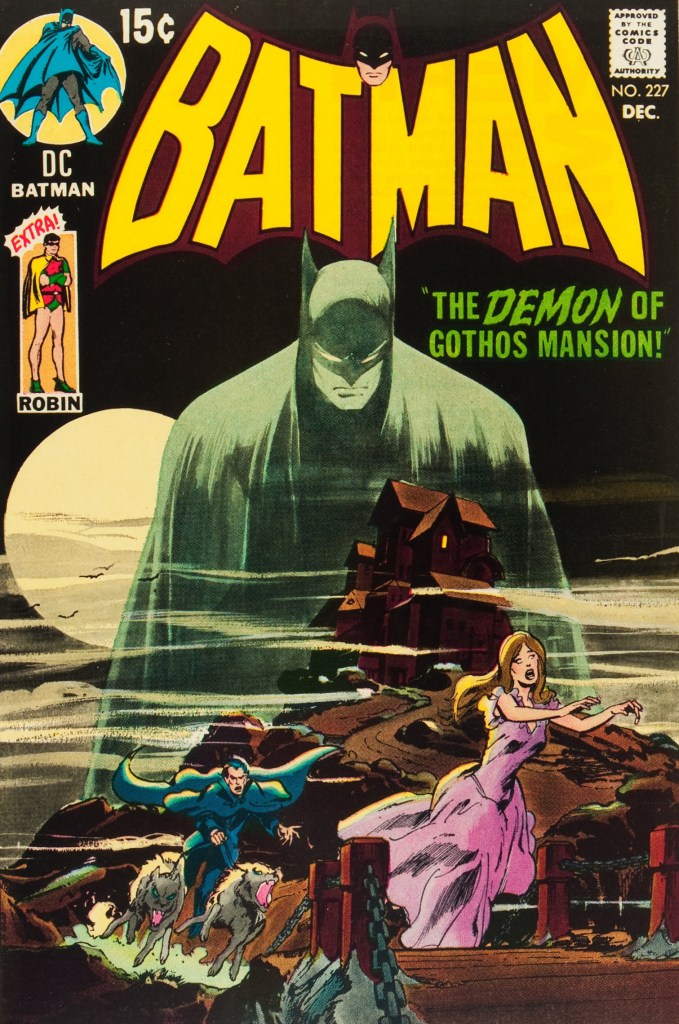

There are comics characters I love, but I no longer obsessively follow their every adventure. I’ll always have a special place in my heart for Spider-Man and Batman, but you know, you’ve seen Bats punch out the Joker once, you’ve seen it all. Sometimes, you just want a sense of closure.

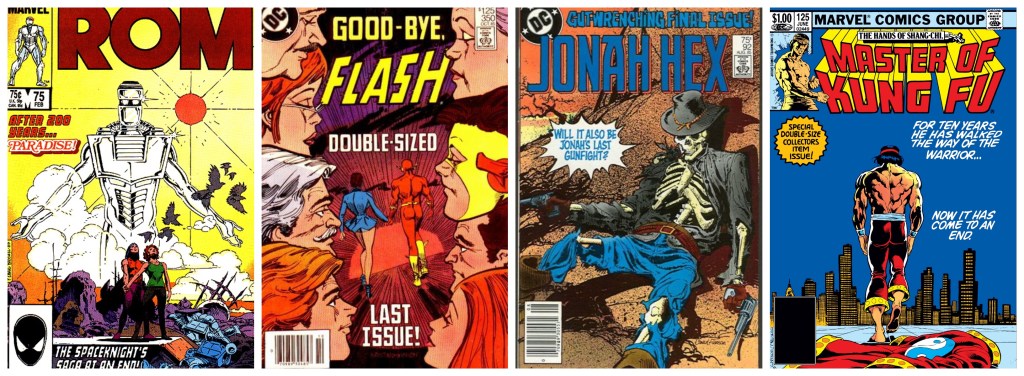

I guess that’s why I have a nerdy fascination with picking up the final issues of long-running comics series, because it feels like a definite ending to the story. It doesn’t really happen much anymore, because there’s always another reboot, but for a while in the mid-1980s, Marvel was kind of OK with wrapping up entirely the stories of characters who had reached the end of the line – Ghost Rider, Master of Kung Fu and ROM among them, while rival DC Comics cancelled almost every non-superhero comic they had in a massive genre purge in the early 1980s, as well as long-running series like Flash and Wonder Woman in favour of reboots.

A cover trumpeting “final issue” teases the reader that this story really, truly matters, unlike the more common “stealth cancellation” tactic these days where a comic book just quietly vanishes.

The ending of these stories could be uplifting – Ghost Rider finally breaks his demonic curse to walk off into the sunset, ROM gets his humanity returned after winning the Dire Wraith war – or surprisingly bleak, when Iron Fist is shockingly murdered in the final 125th issue of Power Man And Iron Fist, ending what had been an entertaining bi-racial buddy superhero tale on a note of discordant tragedy. (Iron Fist came back from the dead, of course, but it wasn’t for several years.)

Other final issues serve as a farewell to dying comic book genres – Jonah Hex #92 puts a capstone on the western saga’s classic years, while G.I. Combat #288 was one of the last war comics in a once-dominant subsector of comics. From the mid-’70s on, one by one the popularity of long-running horror, western, war and romance comics faded so that by 1985, from House of Mystery to Young Romance, almost none of them were left. Sometimes the endings were pretty abrupt – the saga of the bizarre “Creature Commandos” is wrapped up in an utterly slapdash one-page story in final issue Weird War Tales #124 that just shoots them off into outer space forever!

Some got a happy ending that stuck – ROM ended his series in 1985 and while there have been a few revivals at other comics companies of the basic concept, the Marvel version of ROM has never returned – not for creative reasons, but because of tangled copyright wrangling. I do like the idea that the spaceknight got to just walk off into the sunset for good.

I know few characters stay dead when there’s valuable intellectual property to mine – pretty much all of the characters mentioned above have come back in some form or another – but the end of a series after 100, 200 or 300 issues still feels like a pretty firm full stop on a comic’s history. The modern revivals, even when they’re great, often feel like echoes of the past rather than something truly new.

People have been predicting the death of print comic books for ages, and it’s still shocking to see how low sales figures for print comics are these days when their stars go on to headline multi-zillion-dollar movie franchises. But I’m hoping they stick around as long as I do. I do like a final issue, but I also don’t want to see the gut-wrenching collector’s item last issue of Action Comics or Amazing Spider-Man anytime soon.